This essay is a part of Negation's Organizational Culture Dossier. The rest of the collection can be found here.

You call it Pleasure to be beguil’d in troubles, and in the most excellent toy in the world, you call it Treachery: I would you had your Mistresses so constant, that they would never change, no not so much as their Smocks, that you should see of what sluttish Virtue, Constancy were. — John Donne, “A Defense of Women’s Inconstancy”

“What do Communists think people are?” she asked.

“They don’t mean quite what you see,” I said, fumbling with my words.

“Then what do they mean?”

“This is symbolic.”

“Then why don’t they speak out what they mean?”

“Maybe they don’t know how.”

“Then why do they print this stuff?”

“They don’t know how to appeal to people yet,” I admitted, wondering whom I could convince of this if I could not convince my mother.

— Richard Wright, Black Boy

“The problem is me” is the liberal credo par excellence. Combat it always. Liberals theorize that politics is ethics en masse and the world is like this because too many people fail their ethical obligations: too many white people are racist, too many men are sexist, too many capitalists are greedy, too many consumers eat meat, too many consumers buy fast fashion, too many consumers drive to work when taking the train would be only a little less convenient, too many voters keep putting up with genocide, too many workers let their boss walk all over them, too many protesters just listen to the cops. Thank god there’s still a few good people in this world, still fighting the good fight. Thank god our kid’s so tolerant. Thank god our church is such a queer-affirming space. Thank god our manager looks the other way when someone pours a free drink. Thank god our punk house still enforces masking. We can’t fix everything, but we can carve a little good world out for ourselves, and treat each other right. The prime mover of history is the individual, stamped into aggregate millions of times, and how well he strives by his Golden Rule as contoured by history. Against this, communists insist that norms and dark urges are themselves handed down by larger systems and that we can study to understand how these systems are reproduced, seize power over them, and transform them.

These systems use our hearts to feel, our heads to think, our hands to wreak havoc. But they don’t own us, not all the time. No human is definitively won over to the old world or the new. Our minds are full of contradicting desires—I want to learn and I want to be right; I want to go out and I want to stay in; I want you to do something and I don’t want to be a bother; I want to cast off all my privileges and live a warrior’s life that brings the United States government to its knees, and I also want to die old, twenty years retired, surrounded by lovers and creature comforts, in a beachhouse in Arcata. These wants don’t contradict inherently, but in the course of living a life, in living only one life one place at a time, they jostle each other out. We can’t know which of these desires builds out the new world, and which slides us back into reproducing capitalism, imperialism, fascism, and misogyny, until we act on them and observe the results of our actions and challenge each other to do better.

The point is not that people are multifaceted or capable of change or anything obvious like that. The point is that our “facets” are just the imprints of the systems that handled us; our successes are collective successes and our failures are collective failures. Personal change is not authored in the cloisters of the heart. It occurs in the dialectical process of acting and reacting, talking and learning, criticizing and feeling consequences.

This process is not always easy to predict. Global crises and revolutionary upheavals have been known to transform the most rote liberals and resigned bores into fastidious and ingenious partisans. Some people just need to move out of their parents’ house, or try a new drug regimen, or find a new lover, or a better job, or a worse one. Some people will change entirely on their own initiative for reasons we simply can’t explain. But there is also a Marxist science of deftly transforming human beings to better suit the new world, known as critique (sometimes as criticism). To my knowledge, the best formulation of what critique looks like when it’s working is “Constructive Criticism,” by Vicki Legion.

While critique works on any scale, and you can apply it to sort out personal ethical problems, as a technique it has key differences from how ethics are understood in capitalist society. For example, critique never involves labeling—you can critique an evil deed, but you can’t call someone evil—and it never involves punishment, threats or coercion. Threats, coercion, and force all can be weapons of resistance in a tactically informed struggle against an actual enemy, but structurally they are internal to the capitalist war of all against all and when we use them on one another we foreclose ourselves to that war. (If the children of capitalism—monsters, all of us—cannot build communism, no one can.) The mindsets of punishment and labeling, on the other hand, are just plain errors of understanding that distort our analysis every time, including when dealing with enemies.

Critique has been an indispensable tool for every Marxist movement since Marx, especially during the Chinese and Vietnamese communist revolutions. But in my experience organizing here in North America in the 2020’s, I’ve found critique has fallen out of practice in favor of scapegoating, disposability, ostracization and black-and-white thinking on the one side, and unearned unity, whisper networks, predatory peace and defensiveness on the other. People assume that if you intervene against one side you must be making space for the other, but they are two pieces of the same process. Fear of hurting or estranging a comrade with an out-of-control cancellation process makes you hold your tongue, or makes you touch on the matter lightly rather than going into it thoroughly, as if every human matter was as easy as laggards to hearten and heads to knock together. And it is this great network of unspoken trespasses, of cruelly forgiven debts, this theater that “no one here has done stuff like that,” that fills this great moral cloud above us, until it breaks and dead Dorian Gray spills through the portrait and we are litigating every wrong at once and we’re just sick of the whole scene.

This essay will be split into two parts. In the first part, I will re-summarize the 7 rules of constructive criticism outlined by Legion, updating them with examples from my own time organizing. In the second part, I will give my theories for why critique is flagging on the left and this new culture of silence has taken root.

Seven Guidelines of Constructive Criticism

As I mentioned, these tenets were first set down in 1975 by Vicki Legion[1] and I have not edited them much. My aim in reposting them here is mainly to introduce them to a new audience and show that the practice of criticism can be applied to seemingly knotty problems of organizing even today.

Guideline 0: Have Good Intentions. Start from a desire for unity. When you criticize someone for their words or actions, you aren’t trying to punish or get back at or make an example of them. Rather, you want to convince on a deeper level that what they did was wrong so you can both be on the same side again. If you can’t feel genuine love and comradeship for the person you’re critiquing, you aren’t ready to critique.

Critique then is not the right tool for every situation. You can’t critique your enemies. To pull examples from the recent student movement for Palestine, when we attack the dean’s hypocrisy or brutality we’re doing so to win sympathy from observers—we’re not actually trying to critique the dean. Perhaps a close friend or family member could critique him, if they had Maoist inclinations for some reason. But we cannot, because we don’t have the leverage required to actually change his mind. So we use force, threats, bargaining, intimidation, and other methods—in this case all well-deployed, because they orient and regiment struggle.

But “enemy” is not a poetic term here. It refers to the actors mechanically invested in opposing you here and now, not a class of people. For the example of a student encampment, an exhaustive list of enemies would be the university administration, the cops, and right-wing journalists and instigators who show up to your encampment for the express purpose of sabotaging it. Everyone else, from the anarchists whining about you on social media to the above-it-all townie just asking questions to the sanitation worker pissed about your graffiti to the camper evicted after a history of abuse is discovered, should be approached as a peer in the struggle. When you critique them, you do so with their needs in mind, to protect and educate them and strengthen them for class war.

Guideline 1: Be Concrete. Describe concretely what someone said or did that was wrong. Name everyone involved, use numbers, date and place ranges, etc. Don’t collapse multiple actions into a single inference about a person’s intentions (however reasonable your jump) by calling them racist, sexist, ignorant, vain, dogmatic, vacillating, people-pleasing, etc. Don’t refrain from value judgments—if the actions were racist or sexist, say so—but keep the focus on the actions.

This has several advantages. Number one, as Legion points out it’s just a more accurate way to view the world. The supposition that we can look into the heads of others and assign traits to people is a product of petit-bourgeois[2] ideology that says the rich are “smart,” the poor are “lazy,” the jailed are “criminals” and so on. Number two, it leaves people a way out. All the other person has to do is take the L and stop the offending action (plus some other stuff; see Guideline 3) and they return to your good graces. Number three, it has the characteristics of a real report rather than hearsay. People who hear about it are themselves stricken by whatever normative claim you’re making, and get a piece of history, instead of just hearing some canard that could mean anything.[3] Number three-point-five, when you deploy verifiable specifics and back it up with evidence, it’s much harder for the critiqued party to drag you into an unwinnable, unlosable battle of vagaries where sides are chosen mostly based on who likes who. What’s a better indictment: “PSL are authoritarian/cultish/tankies/feds/etc.” or “On Friday, June 2nd, 2020, less than a week after George Floyd’s death, PSL protest marshals at a Baltimore riot tackled a man who’d been shooting fireworks and handed him over to the cops, and if you ask major PSL heads about it they’ll either deny it or downplay it.”[4]

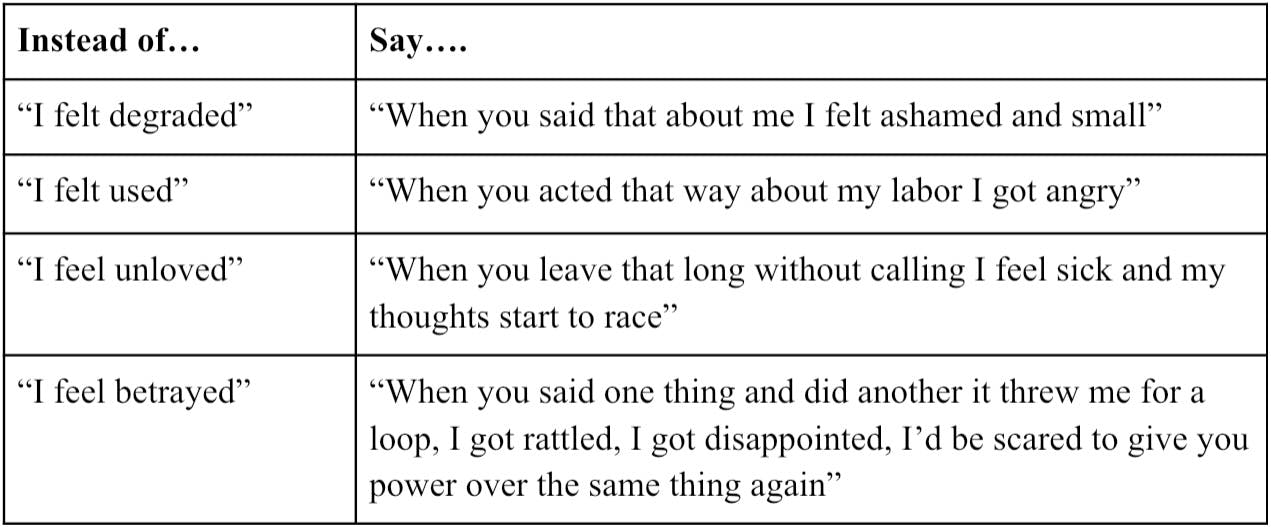

Guideline 2: Describe Feelings. Name the way you felt when the other person did what they did. Avoid weasel words that imply the other person made you feel that way: your feelings are a product of your values as they mediate the outside world, not some inalterable response to the outside world itself. No one has wizardly control of the way you feel: those feelings are yours. But those feelings aren’t wrong and they tell you what you need to know, so you should name them.

Guideline 3: State Wants. Say what you want to see change. Name who should change their behavior and what they should do. Don’t fall into vagaries about what kind of person they should become (this includes overly broad asks like “just think a little harder next time” that might as well come from Saint Peter). Don’t merely tell them what not to do. Give them a real program for self-actualization, not a hellpit to walk over forever.

Legion’s exercises for this rule cover mostly mild issues. If a reading group is babbling too long and never getting to the meat of the text, you should say you want it to run longer, or ask for more structured discussion. If a comrade is gossiping and talking only in asides, you should ask them to state their opinions forwardly at meetings. But it applies as easily to the most serious crises of justice. When I was a sophomore in college my best friend told me that he had recently sexually assaulted someone we both knew. I was completely unequipped to handle this kind of situation and my moral calculus ballooned with the all-or-nothing question of “do I stay friends with him or cut him off?” Note the individualism and narcissism of this framing—“What do I value more, my friendship or my moral purity?” If I had approached the predicament from the perspective of actually bringing him over to a new personhood and securing the safety of the survivor, I could have used my position as his best friend to criticize him and push him to take reparative actions. Obviously for the survivor’s safety I should have asked him to drop out and leave the campus. All I would have been doing then is releasing him to the wilderness to offend again, though, so I could have suggested additional courses of action to transform him as a person, like getting a therapist or quitting drinking.[5] Eventually he decided to do all those things on his own, and he’s a completely different person now. But it took him a year to figure it all out, and that was very destructive.

When you tell someone what you want them to do, it should relate directly to the behavior to be corrected. This is not community service, and it’s not the labors of Hercules. Nothing in the process of critique involves punishment! Of course in cases like the one above, it may be necessary to remove someone from a community for the safety of others, and this is only ever going to feel like punishment. But there is a difference between something feeling like punishment and it actually being punishment.

Guideline 4: Explain the Purpose. Explain why their words or actions were in error, in terms of harm done to others and to the cause. This is a form of political education, which as Fanon notes should never be a lecture or an attempt to rule the mind by fiat—rather you need to genuinely convince the other person that what they did was wrong by making them aware of their own power and the urgency of the situation. A person becomes answerable to critique, both now and for the future, when they understand “that everything depends on them, that if we stagnate the fault is theirs, and that if we progress, they too are responsible, that there is no demiurge, no illustrious man taking responsibility for everything, but that the demiurge is the people and the magic lies in their hands and their hands alone.”[6]

Sounds exciting, but how do we do it? Generally, if you want to convince someone, you have to start from their perspective and work backwards. You can usually expect to learn something as well.

Let’s say you’re planning an action that you absolutely cannot let the media, the police, or anyone else get a hold of and some of your comrades are violating opsec principles even after learning them—they don’t bother using codenames, they don’t mask or dress in bloc at the action, maybe someone even gets drunk at a party and tells a funny story that includes compromising details of the plan. This is a serious mistake that could get someone locked up or killed if history turns the wrong way! How do you use criticism to deal with the situation?

Often, the issue is not that people want to sabotage the operation or are lazy, but that they don’t understand the mechanics of such a risk. Simply handing them a zine[7] won’t help because the classics are written broadly and can’t explain why the specific practices you have in mind are feasible, worthwhile, or suited to your action. Usually those zines will act like your main concern in security culture is hiding from the feds, which simply isn’t possible in any situation where the feds want to find you—your comrades, well aware of this, will write you off as obsessing over ludicrous Spy vs. Spy scenarios that no half-decent organizer would factor into any plan. When I tell people it’s necessary to use codenames, I stress that it’s not about “what if someone here is a rat.” It can also be about what name you shout instinctively when you’re pulling someone away from a journalist or a right-wing agitator. When I explain the urgency of Signal hygiene practices like leaving chats you aren’t active in, nuking old chats, setting disappearing messages, etc., I stress that of course Signal is a limited hangout and the NSA can look at your phone screen whenever it wants and so on, but the practical worry is if a comrade gets their phone taken by the cops. It’s never enough to repeat slogans from theory or zines—you have to work backwards with people from their own concerns, especially when criticizing them.

Guidelines 5 & 6: Paraphrase & Empathize. These both involve being the subject of criticism, and they are so interrelated I tend to club them together. In real life when someone criticizes you, chances are it won’t be all hugboxed or perfectly follow guidelines 1 through 4. When that happens, it’s on you to divine what amends they’re asking of you, what actions they’re criticizing, what emotions they’re feeling, and what harm you’ve done to others or to the communist project. You do this by empathizing with your critic to understand where they’re coming from, and paraphrasing their critique at the end of it so you can be sure you’ve taken them at their word and get clarity if you’re wrong. Critiquing them for a vague, cryptic, unfair, cruel or politically misinformed critique can only happen after you’ve deduced a good critique for yourself.

Recently, I went canvassing to gauge neighborhood support for a mutual aid distro that some folks were intending to host regularly in an abandoned lot. Due to my haggard mental state at the time, as well as my petit-bourgeois tendencies, I wrote up a weirdly gonzo report-back on the action, indexing the class makeup of the houses we knocked by referring to some as “beautiful” and others as “ratty” and ending with a call to survey “poorer/blacker areas” to get a more representative view from the base. Nobody was asking me to profile the houses like that, and it was especially silly considering the miniscule number of doors we knocked. They just wanted to hear how it went and what people said! But the word choice definitely didn’t improve things.

After I posted it, the group chat went dead for 24 hours, then a black member quit the group in protest, citing those phrases of mine. In a later mediation session where I was not present, the other member called for me to be removed until I “do the work” unlearning the classist and racist tendencies that caused me to write that way, but they could not specify what they meant by “doing the work” when pressed. I was unable to model rules 5 & 6—I didn’t dare to reformulate their critique in what might be a more helpful way and just apologized profusely to everyone and offered to comply with their request. This sort of instant fawning is its own sort of defensiveness—I was trying to defend my behavior from critique by scapegoating it onto my essence as a person, which is, again, not a real thing. Kicking me from the group would do nothing to address the underlying collective tendencies that led to my brazenness and the other member’s defensiveness[8] and wouldn’t even punish me since I have plenty of other projects to organize with (and the prospect of sitting at home playing Baldur’s Gate 3 instead of lugging folding tables around in the summer heat doesn’t sound very punishing), and in any case, expelling someone for insensitive word choice is just not something that happens, which is why the group denied the other member’s request. Instead, we came together as a group to talk about our collective issues with the other member absent. The work of neutral parties was needed in this case to repair the critique, though ultimately they didn’t state any wants for me beyond “Don’t do that again” (violating guideline 3) and could only speculate on the other member’s feelings (a poor application of guideline 2). The group succumbed to burnout shortly after.

Guideline 7: Defensiveness. This one is less a pithy rule and more a set of tips for heading off and handling something that will inevitably come up when making criticism. It’s easy to see why people get defensive of criticism, surviving as they do in a fascistic capitalist society. When “critique” occurs in a capitalist society, it generally is done to feed and launder consent for the police and prison system (“Junkies like you are sick in the head. You turned down every helping hand you could’ve gotten. How could you do this to your ma? To your pa?”), compel people to work (“This is the third month where you failed to meet our metrics. If you don’t pick it up, we’ll have to let you go”) or guilt people into compelling themselves to work (“You didn’t cover my shift and now I’m going to get fired. Hope your beach trip was worth it”). Most people who end up on the left have painful associations with being labeled, coerced, or guilt-tripped, and rightly see those maneuvers as cynical and self-serving tools of capital. The intent of criticism is never to do any of those things, but it still may be read as such! People also, less sympathetically, like the social power and trust they get from being perceived as morally infallible, and see critique as an attack on that power.

You can head off these hazards by clarifying your intent ahead of time: “I have some issues with how the encampment is being run, but I want to make it clear I’m not trying to call anyone a liberal or get revenge on the planners for what went down the other day. I know we all want to free Palestine and I’m bringing this up because I know the best way to serve our strategy is to serve it with my mind and speak up when I see problems, not merely carry out orders without questioning them.”

If someone is getting heated and defensive, you can ask them to repeat back to you what they think you said, and clarify from there. Pull the conversation away from demands, epithets, and clapbacks and towards feelings, wants, and clarifying questions.

If someone is consistently rising to your criticism, they’re probably stereotyping you as one or another type of leftist they don’t like. They’ve enrolled you as a character in a mental drama which you have no way to engage in. Sometimes you can jar people from this mindset by asking point-blank how they expect you to get out of the box they put you in. “Look, I know you think I’m an anarchist wrecker, but I honestly disagree with the other anarchists on X and Y, and I thought it was clever when you pointed out that Z, so when can we move past this and actually talk politics?”

One tip I would add to Legion’s list is that it’s always better to deliver your critique in person, where tone is observable, than over text.

If none of this works, and the same person or group is consistently and flagrantly resistant to critique (and especially if they employ cruelty or dishonesty in their resistance), then critique is not the weapon for the situation. Perhaps no one is essentially anything, but your time and resources are limited and litigating a maelstrom of human feeling while waging a war is incredibly taxing.

You have to consider the way that power affects your ability to be heard. In “Constructive Criticism,” Legion tells the inspiring story of Allyn and Adelle Rickett, US spies in Beijing who were captured by the Chinese Communists in 1950 and so totally transformed by the application of patient, gentle critique and collective problem-solving that they could be released without issue in 1954 and continued to speak fondly of Chinese communism until Allyn’s death in 2020:

Because oppressed people share a fundamental common interest in socialist revolution, our conflicts should not be a clash of one personal interest against another, but a cooperative effort to discover the resolution that will advance the whole. Rickett described how this attitude looked in practice. “In our cell we tried to look at our differing points of view in the detached manner of solving a problem instead of each trying to force the other to accept his own ideas and win the argument. [My cellmate Han] learned to put himself completely outside any disagreement which arose. Concentrating his energies on solving the problem, his entire attitude bespoke a desire to convince me rather than batter me down. No matter how insulting I became he would not lose his temper. If I were not prepared to talk, he was willing to wait. When I ranted and raved he would ignore me. He kept plodding away with the determination of a small bulldog, only one thing in his mind, to help me reach the root of my trouble.”9

While this shows just how much power we Communists have when we think outwardly of each other as the explosion of potentials that we are, and shows that souls can be invented anywhere, Legion is quick to note that the Ricketts being a literal captive audience creates leverage that doesn’t exist in day-to-day organizing.

Five Reasons for the Culture of Silence

Critique was central to the Chinese and Vietnamese communist revolutions and remains key to similar movements like the Filipino NPA and the Indian Naxalites. Mao missives like “Combat Liberalism” and “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People” complement Legion’s essay as if all are speaking with one voice. But in the North American Left in the 21st century, critique has been so married to punishment, coercion, and moralism (the liberal’s three magic weapons) that it cannot be invoked in an org without doing it harm.

It would be a godsend if cancel culture (what I will insist on calling the “culture of silence” throughout this essay) was merely a far-right mirage comprised of impotent Internet-connected teenagers and other basement-dwellers, beneath the concern of any theorist with more at stake than the good name of his favorite English standup comedy personalities. I certainly don’t want to be writing about this, but in my time in the “real world” I’ve seen more groups nest themselves in inescapable knots due to this negative inward-looking moralism than any other issue. It’d be another thing as well if these were just the growing pains of a sexy, ruthless, QTBIPOC New Left shrugging off the Old Left of grouchy white class reductionists with newsboy caps and hamburger mustaches, but this isn’t so. If you get your impression of the way Left spaces work from the Internet then you will be floored at the way cis white men in real-world spaces glide smoothly over controversy while women (especially trans women) and people of color take the ax for every collective issue.

I’ve already suggested how to escape this riddle—let’s take one step on good faith and study and apply Legion’s principles of criticism. Introduce the practice to everyone in your life and everyone you do work with. But how did we get here in the first place and what is truly within our control? What do we need to understand about the shift in culture before setting forth?

Reason 1: Liberals won the Cold War. The number one cause of the downfall of critique is that the Left is, depending on who’s counting, somewhere between its third and sixth straight decade of wholesale political defeat and intellectual dishevelment. The old ways of regimenting and articulating class struggle—of ensuring people who live together and work together also struggle together and build together and learn together—are in serious retreat. In the US, unions have been bought out, and the country’s largest socialist party can’t crack 100,000 members or keep its nominal voice in Congress from voting to fund the Iron Dome. Active membership of local orgs rarely tops a dozen people. And most people turned on to the class struggle aren’t part of any org at all—they struggle alone.

Practically speaking, this means communists for the most part lack the community bonds required for us to actually rehabilitate one another or critique from a context of trust, patience, and safety. Read this 2013 resolution from a now-desiccated Maoist group on standards of feminist conduct and you’ll see the pressure put on by these material conditions. They conclude that though critique and rectification was a worthy tactic of Communist parties in the past, exile is all that modern organizers can responsibly find within their capacity:

Rectification means conducting self-criticism widely before the masses, submitting the fullest account of one’s conduct and history to public scrutiny, and following through on a course of political activity of struggle against women’s oppression, which must include ongoing transformation of the individual person, similar to what Yokinen successfully carried out under the leadership of the CPUSA.

Recognizing that there is no organization in the US today with the necessary base, prestige among the masses, and scale to conduct such a process means that in the current objective and subjective conditions, successful rectification of individuals for male chauvinism should generally be pursued, but will inevitably continue to be the exception rather than the rule. The most important thing is to struggle against the small-group dynamics that are a soil for male chauvinism and prevent the organization of women. Violence against women will not end without the organization of women.

This line is generally correct, and when someone is found to be an active danger to their comrades, it’s better at the end of whatever process to release them to the wild than to keep them in the org and take your chances. I’d love to live in a world where that isn’t true, because ultimately it lets everyone off the hook, but we aren’t there yet. Certainly, many orgs attempting to resurrect the practice of critique and rectification without the requisite community groundwork instead birth monsters; critique is misunderstood as “the Communist way to do punishment” rather than a radically different way to approach human beings.[10] Coercion, cruelty and shame work about as well to deter chauvinist attitudes when employed by a Maoist sect or anarchist squat as they do when employed by the police.

On the flip side, people sometimes refrain from acknowledging or investigating chauvinist tendencies (or anything at all) in their org because the situation is so bleak and the enemy so vicious that any loss in momentum or perceived weakness could be compromising. Besides being cowardly (how quick come the reasons to do what we like!), this is strategically unsound: critique is how we build a culture of discipline capable of taking on the monstrosity that awaits us, and the more we practice it, the better a tool it becomes. People hurt or sidelined by abuse leave the movement and rarely return—and we will feel those losses more and more in the coming decades. Racism and sexism are so corrosive to movements that they can be used as reliable tells that someone is a federal informant: J. Sakai notes in “Basic Politics of Movement Security” that, while any cop can act “down” (he’s not catching charges for whatever you do), agree with the party-line on whatever (it’s all gibberish to him), and style himself like a leftist, the piggish attitudes inculcated in him by his police culture will reveal themselves over time, if you are actually vigilant for them.[11]

But the culture of silence is more than a tactical retreat, and it does not primarily or even reliably dispose of abusers. Typically, a member is marked for disposability first, and exiled for peccadillos later: this grows truer as the strength and formality of the association grows weaker, as the Manichaeism of impotence is a psychological problem. If you can’t go on offense, you go on defense, and if you’re on defense, you have everything to worry about. If you have only yourself to instruct and only yourself to watch, politics will cast its shadow only in your heart—your little dramas, what kind of milk to get at the grocery store, what name to write at the ballot box, what to say to the stranger at the bus stop, become the most political decisions you make. Beauvoir’s report on the Manichaen mind of the housewife—exiled from history, forever at war with her dilapidating prison pen—resembles all too well the harried monster-of-the-week attitude of lonely atomized leftists: one cannot pursue the Good through positive projects, one cannot beat the Devil when God is dead, so one tilts for the “abolition of evil,” dusting every corner, batting away every fly, and there is always more dust and flies; you can’t get rid of dust and flies.[12]

Critique is a process of construction, not of purification; it involves looking outward, not inward. But if you have no project you feel confident in, you have nothing to build and no outside to look to.

Reason 2: Major advances in communication technology allow people to think together without any need to live together, work together or struggle together. How did people with no connection to a party, union or other org get turned on to left-wing politics in the first place? Historically they’re an anomaly—in the 19th and 20th centuries, it was the Party who taught workers about the class struggle, and workers learned about the analysis of their conditions and the possibility of an alternative at the same time they joined the Party. Often it fell on the Party and attendant cadre organizations to teach workers how to read and write, because capitalism didn’t bother. This isn’t true anymore: 86% of global adults are literate, and the Internet enables us to teach ourselves about the world, come to informed conclusions, and even debate and criticize each other without the context of any mediating institution or project.[13]

This is all just grand and it means that despite being on the ropes politically, the Left continues to hold people’s imagination. Shockingly high numbers of Americans say they prefer socialism to capitalism.[14] Crowds at anti-racist and anti-imperialist protests are larger than ever before, and cover broader spectra of society than ever before.[15] Antifascism spreads much farther as a norm than a practice, even in times of quietude.[16] It seems likely this organic, peer-to-peer political education will be key in launching us out of this political sequence, once we’ve developed the right innovations to channel it. BDS was one such innovation—before the Internet, that kind of solidarity call for a targeted boycott would have been impossible to propagate except through a union, vanguard or state-approved NGO, but since choosing not to buy something is exactly the kind of low-stakes action that can be encouraged indiscriminately across neverending networks of people (consumers of the world, unite!) it enrolled millions in a headless fluid conspiracy. Yes, it’s dumb that Starbucks has taken the brunt of the financial losses since October 7th despite not being on any BDS list and not having any locations in Israel, but it’s mostly just a goofy footnote to history and the boycott movement has dealt huge blows to the economic viability of the Zionist entity, and sharpened, concentrated and articulated global solidarity struggles—everything from the student encampments to the counterlogistics work that routed Elbit in Cambridge, MA to the blockades of arms shipments by dockworkers in Greece all follow the BDS line and are intelligible only as arms of BDS.

In body, in work, and in struggle, people are lonelier than ever. But we get to think together and come to mass conclusions. This kind of thought, disengaged from struggle, can only really talk about what should be, not what is to be done—what’s right and wrong about the current political theater and what is pious or impious personal conduct for the default white male American Leftist. Strategy can’t be discussed except through fantasizing about moving political figures around on the world like avatars in a 4X game (“why doesn’t Biden simply pack the courts,” as if Biden is a secret leftist waiting for an opening in the political will) or by assigning an explosive Kantian butterfly effect to the private rituals of American liberal life (home of voting discourse, should I buy a thing discourse, etc.). Despite everything, these discussions do grasp something like real stakes eventually and provide an arena of political education that will be useful in the coming decades. We should be looking to get off the Internet and so on, but most readers this far into this essay already know that.

Reason 3: The logic of the prison has come to dominate every aspect of capitalist life. The Internet is not some apolitical scientific discovery, and by this I don’t mean merely that it was developed by the US military as a counterintelligence tool modeled off of the tunnel networks of the Viet Cong[17], or that 70% of it sits in server farms in northern Virginia. Everything about the commercial Internet was put there to serve a global order of capital, in heavy rotation since the 1970’s, that prizes circulation over production, fluidity over structure, contingency over strategy, personality over community, discipline over struggle, and disposability over care.

While there is more to this shift than my humble essay can diagnose, a major part of it is the spread of the prison and the logic of the prison over all human interaction. In the last quarter of the 20th century, the incarcerated population sextupled—from 328,000 people, or 161 per 100,000 residents, in 1970, to 2 million, or 700 per 100,000 residents, in 2002, the year Angela Davis published Are Prisons Obsolete?[18] In the same time frame they got uglier and more crazy-making: Foucault talks a good bit about how both prison reform and prisoner rehabilitation are internal to prison logic, but the prison has had little need of late to lean on these dithering tools for homeostasis. Pell grants and other educational pathways for prisoners were removed en masse in the crime bill of 1994, and even bodybuilding equipment was removed from most prisons shortly after.[19] Supermax prisons emerged in 1983 ostensibly to contain the most “dangerous” prisoners (UNHRW dryly notes most of them are not that dangerous) in 23-hour-a-day isolation, a “slow and daily tampering of the mysteries of the brain.”[20] Davis points out that little separates the supermax from the “Pennsylvania system” of 19th century reformers, who supposed you could free the soul by entombing the body in monklike solitude and silence, except that “all references to individual rehabilitation have disappeared.”[21]

What is the point of prisons? What is the point of their recent engorgement on human lives? The easy Marxist answer is that they provide near-free labor for a few lucky capitalists, which, in a society where everything we need to live relies on the ability of some idiot to make it into an easy buck, is pretty important. Global profit has fallen consistently since 1970; capitalists will lick and lick at the ice cream tub for a new slave until they find one. And certainly the prison-industrial complex is not nothing; while only 6,000 prisoners in the US work for private corporations, far more (800,000) toil away for the Bureau of Prisons directly, generally on the social reproduction of the prison itself—where the quick buck is made by Aramark and other companies subcontracted to feed, clothe and treat the prisoners, since they get to show up with their job done for them—but also on other government services. The main industry of most counties along the California-Oregon border is now government-funded fire prevention, and about 30% of wildland firefighters are prisoners paid $2 an hour at most.[22] The unwaged labor of the prisoners pays the wages of the “free” firefighters and protects the region from economic ruin (and fiery death). However, all of this is just moss on a log and doesn’t really do much to defray capitalist crisis, as James Kilgore argues here; the labor of the Global South is still almost always more attractive than prison labor, as there’s no red tape about security. Capitalism will survive without Aramark, and the California government could hire only free people if it really wanted to.

Perhaps the man in the street is right, then—prisons act as a deterrent to crime. Certainly, this would be effective armor for capitalism, since all acts that seriously jeopardize capitalism either are illegal or will be. But deterrence has a diminishing rate of return—the prison can only be so scary in your mind’s eye. Statistics about harsher and gentler sentencing seem to bear this out. I actually think you do need Foucault for this: the prison fashions a whole array of architectures, attitudes, habits, and tactics that add silent stress to any action that isn’t walking down the cattle chute of capitalist life, and these tactics in turn fashion the prison, as well as every other part of postmodern society. Deterrence is one such tactic. The gridding of time, which lulls your mind with its rigid, arbitrary, but always consistent rhythm is another: think of the bells that ring at bizarrely specific times to announce the changing of classes in school. Gamification, which I once heard a tech instructor refer to as “the only way you can get people to do what you want without force,” might as well be called prisonification for all the boxes it checks on Foucault’s list: an exacting tally of credits and demerits; the gridding of time with countdowns, resets, and manufactured urgency; the gridding of experience, different “levels” and “badges” to acquire, perhaps attached to new permissions; stable, predictable tests and evaluations deployed at predictable times, often pitting prisoners against each other; individual profiles with stats you can check.

It’s easy to imagine that prison wages, so minute as to be something unrelated to actual money, act more like fantasy gold coins to the prisoners, clicking up and down in unjust but certainly reliable ways. You cook and clean and launder without remark, because anything is better than boredom, and because the trail of little rewards makes it look like a story of progress, at least until you need to buy a cig, or an extra helping of food, or a doctor’s visit and get knocked back down to 0. The mechanics of the prison teach us to want for ourselves what capitalism is doing to us.

Many aspects of the logic of the prison are actually just the acoustics of collective life as created by capitalist technology. Panopticism, for example, is just how digital surveillance works. You don’t know if that camera is being monitored, you don’t know if they’ll play it back, you don’t know if it’s on (fake Ring doorbells go for $12 at Walmart), and you can’t, after a quick scan of your surroundings, always be sure if there is one. You don’t know if the NSA is spying on you through your phone. Seems like they couldn’t possibly pay enough guys to hear all those phones, right? You don’t know if there’s a file on you. You don’t know if a potential employer will see your edgy post. But your risk calculations have to err in favor of assuming the worst, since the consequences are worse. The Man barely pays out for security at all. The mechanic is just the one-way mirror of video telecommunications as wielded by organized power.[23]

Foucault also talks about the deputization of prisoners: in schools you have hall monitors, in retail “assistant managers,” etc. Of course, his argument by the time we get to the end of the book isn’t that all the institutions on his list resemble prisons, but that society itself is a prison. Well, there’s always that urge in life, especially when you’re down, to make the peccadillos of random nobodies into your most grievous injuries. Sometimes someone wedded to that thought pattern gets deputized at their institution; sometimes they make do with remarking on the news and disapproving of their neighbor’s boyfriend. But there was never such a flow of random nobodies for us to get our kicks on before this hyperspeed era that threw us all together.

The anonymity of the early Internet rather infamously encouraged all kinds of bad behavior, but it was mostly collective bad behavior—not the thrashings of asocialized losers set loose upon a placid symposium, but whole rings of prison deputies enforcing an order handed to them from their carceral lives. Cringe-culture websites like Fat Chicks in Party Hats matured into institutions of soul murder like Kiwifarms[24], which would record everything about you if your divergences fascinated them sufficiently, every day you had, every shirt you wore, every weird little thing you said and weird way you said it, everyone in your life and everything they did, every food you ate, every face you made, every way you jacked off. If questioned, they would appeal to broadly progressive values—maybe you were racist, or homophobic (a much more serious offense in 2009), or you sexually harassed women, so you deserved it. They were just giving people a taste of consequences. The fact that they themselves were avidly racist and homophobic and enjoyed inflicting every kind of sexual torment within their means did not even register as hypocrisy. Maybe some were just saying what they knew worked to muddy the waters, but many understood that their Bad was different from your Bad—they, after all, had never been soul-murdered.

This brings us to the most useful concept from Discipline and Punish for understanding the culture of silence as an outgrowth of the prison: the case. Everything you do is recorded, it leaves a mark. There is a file on you at your elementary school, at your college, at every place you’ve ever worked, at every doctor’s office you’ve ever used. There is an official story on your height, your hair color, your eye color. There is an official story on what you did that summer for an internship, which you keep waving in front of prospective hirers. Thanks to social media, there is an official story on what you were thinking about and what you were doing almost every day of your life, on a public database that will probably outlive you, which you wrote for the amusement of millions of strangers. Once, this was the treatment of kings. Do you feel like a king?

What does this notion that you are not an individual but a piece of a whole even mean when the whole is this massively fucked? You’re not accountable to your “community” (communities, freed by capital, can be tossed aside and exchanged as easily as winter coats), but to all of society, of capitalist society, of millions of strangers passing you on the way. Hopefully there’s more to collective duty than being nice and not bothering strangers, but even that is an impossible ideal when any transgression stains you forever. There is always an easier way that avoids conflict, an easier way to just hide what’s wrong with you, and if you ever let it out, there is the specter of soul murder. And then, from the other side, when you’re actually building something, and you see a problem, there’s always an easier way to keep quiet, always a way that you’re the prison deputy for noticing.

Reason 4: Labor aristocrats are building a movement primarily around solidarity, not collective self interest. Politics is a way to pursue the Good. To be clear, I’m saying “labor aristocrats” to clarify my epistemic limits, not to invoke some boring Third Worldist point about how only the superexploited people of the Global South can rightly struggle for improved conditions because only they have it in their interest. While it’s just obviously true that people become more likely to risk their lives to change the status quo when the status quo itself puts their lives at risk, and that even the most precarious American worker enjoys security, opportunity, and comfort that any Indian shrimp farmer would die to give to her children, the whole Third Worldist thesis presupposes a massive communist Third World uprising that simply doesn’t exist. If anything, the fact that Indian workers haven’t all run off to join the Naxalites despite twelve-hour days, job insecurity, debt bondage, child labor, chemical burns, workplace sexual harassment, single unit dwellings with six to a room and no bed, smog index ratings above 200 for months at a time, and triumphant state fascism should demolish in one blow this easy inverse relationship between degree of exploitation and revolutionary appetite. Any Third Worldist worth the name would be directing their critique and investigation at Third World leftists, who would probably welcome the novel interruption, and not laying on yet another slam dunk about the American left.

Unfortunately, this is beyond my abilities at the moment, so I will focus on a phenomenon I’ve noticed in my own time organizing. The best model of organizing to come from the 2010s revival of American socialist thought was the base-building model pursued by groups like For the People, the Marxist Center, the DSA (eventually, sometimes), and Philly Socialists. The idea is you pick a local, winnable fight and organize like hell, knock on doors, identify leaders, rigorously onboard, rigorously strategize, until you’ve built a tenant union where a bedbug-infested tenement one stood, or a community garden where a developer-ready lot once sat, or a unionized workplace where some shitty coffee shop owner had once predated on his baristas. This is already sort of a solidarity gesture, because at most only one or two of the people in your organization actually have the problem you’re trying to solve with this project. Your wager is that, through good faith, mutual trust, and the experience of building something together, people from the base will strengthen your org as you strengthen them and become great organizers to replace you, solving a major problem you’re having, namely that almost everyone who naturally wanders into your org is a weird white middle-class nerd who heard about communism online (mostly because of reasons #1, #2, and #3). But this is just the contradiction between workers and intellectuals and it’s nothing new.

What was new (or at least surprising) is that this didn’t work at all. Organized tenants didn’t surge into the org after rattling their landlord into improving living conditions; they mostly kept on being tenants. What connections had been built wore away in the slow hypnosis of weeks turning into years, as people moved, burned out or broke over social or cultural disputes. People had to look at their own hands and realize in disgust that all they had accomplished was doing something good for someone else. Mutual aid groups realized they weren’t “building power,” just giving stuff away forever no better than the church down the street (the horror!), and that their project would end the moment they couldn’t put in the nonstop hours, on top of their miserable jobs, their new life emergencies every week, unless they allowed more of those horrible college-educated white leftists (who for some reason also always had miserable jobs and new life emergencies every week despite being college-educated) to replace them.

Then, in 2020, something happened, and this whole country, black and white, poor and “college-educated,” stood up and demanded the full transformation of daily life, the end of this monstrous regime put on us, the violent civilizing of the American wasteland, going to never-before-seen lengths: 574 riots, 2,382 cases of looting, 97 cop cars set ablaze, probably a dozen dead cops, and at least a hundred martyrs on our side, not because we were tired of working or tired of paying rent or anything like that, but because Black people in this country are murdered by cops every day, in the most gruesome and nonchalant ways, and we watch it on our phones. So many white people showed up for George Floyd that the counterinsurgent messaging was that it was too white![25] And then that beautiful wave lapped back, or whatever, but the long-term electrification of our theory and strategy and efforts was undeniable.[26]

The same rejuvenation happened in 2023 after several years of crushing depoliticization and mounting counterinsurgency—Hamas broke the wall and the movement for Palestine in this country surged with unprecedented life, initially through little cells, coalitions and liberal civil disobedience movements like Jewish Voice for Peace before reaching new levels of articulation through the spring 2024 student movement. Again, it wasn’t because we had trouble with our landlords or trouble with our jobs. Plenty of us do, but it didn’t trouble us nearly as much as those Tiktoks and Reels we saw every day from Palestine, babies pulped, adult men flattened under bulldozers, arms moving feebly under rubble, a horrorshow tour of the blackened hospital, a hand on fire still connected to an IV, a six-year-old-girl’s screams on an emergency call in her upturned car surrounded by her dead family members, a reporter hearing live that his whole family has been killed by Israel, a nine-year-old-girl carrying a birdcage hundreds of miles across the wreck of her city.

Before very recently, if you saw that kind of shit you were living it. Maybe you saw it in a Mondo movie or a CNN broadcast or a punk album cover, but there it was presented by liberals to inculcate liberal hegemony. The shoes at Auschwitz and the skulls at Cambodia were for dead genocides. Why wouldn’t a living genocide turn everything we know about organizing upside down? Why wouldn’t these videos wound you more than some dipshit boss and a leaky faucet? They wound me. They’re the worst thing going on in my life.

Rather than make any overly bold pronouncement on what kind of organizing we should be doing, I’ll just note that, whether base-building or agitating at riots, you’re doing something essentially for other people. You don’t expect the movement to do anything about your problems. We are all creatures of liberal hegemony, so we grasp our unreciprocated collective duty as the liberal injunction to pursue the Good. It’s assumed, then, that everyone else at the organization is a Good Person or else evilly pretending to be a Good Person. Discipline becomes difficult to judge proportionately without relying on Christian/charity mores when everyone in the org is fighting for someone else. There is no Marxist text on how to manage a movement mostly composed of bleeding-hearts.

When someone shows up because they followed the old script, because they want help, they have a fight to win, and that someone is a step removed from the group’s values, a jarring culture shock occurs. Sometimes, they get tarred, feathered, and scapegoated. Sometimes, the whole org just acts confused and ignores it, acts like it’s nothing; how do you critique someone when you’re coming from completely different places and theirs is the one that’s supposed to matter? I have never seen this resolved in a mutually intelligible way, but then again, we’re in a comparatively politically quiet time. Most people who join my org join because they are a leftist of some kind and they want to start organizing. Expectations start to congeal. My understanding from older comrades is this isn’t how things were during the last Trump administration, when hundreds of terrified liberals flooded the meetings and all kinds of fights erupted. We need to train ourselves in outward-looking, constructive struggle for when moments like that occur.

Reason 5: It has always been this way. The worst thing we could do to the communists that came before us is to Edenize them. Communist history is full of moments where leaders insulated themselves from critique and made disastrous decisions, and as many instances of witch-hunting, scapegoating, cynical horse-trading masquerading as “politics in command,” silencing, punishment, and predatory peace. Think of the Stalinist purges, the opportunist elements of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (which were common, and horrible), or the dogmatic and Machievellian culture of the 20th century CPUSA, which Cam’s essay goes into more detail on. Legion would not have written her essay if it didn’t address problems she saw constantly going on. The liberatory spirit and the backwards, bourgeois spirit have always coexisted within those very groups that claim to serve emancipation, and it has always been our responsibility to struggle for the liberatory side. No task is too small, no task is too large.

Notes

- Née Gracie Lyons, an American activist in the Maoist and women’s movements in the 1970’s. Constructive Criticism is her main claim to fame.

- When Legion calls something bourgeois, she’s not using it in the way we’re used to hearing it now. Bourgeois ideas are not bourgeois in the way a salad or a house party can be bourgeois (“the sort of thing you’d only hear from bourgeois people”) but are just those ideas, found in all kinds of people, that keep people off the scent of fighting capitalism and thus serve the bourgeois class. I use the word the same way.

- At an action a few months ago I heard whisper campaigns going on against three people, all trans women, in all cases nothing more specific than “so-and-so heard she’s a creep.” Nothing came of these whisper campaigns at the time, other than some comrades acting more wary and icy than they otherwise would towards these women. Long after the truth would matter for this particular action, I learned that one of the girls had indeed groomed and molested a 17-year-old a few years back. The second one was a “fake top” who supposedly deceived people into sleeping with her by acting like she would be the sexually dominant one when she wasn’t (this accusation is, obviously, meaningless and transmisogynist). For the third, I still don’t know what she did, but I do know she took her own life in between the first and second draft of this essay. It would be hard to draw a more illustrative triptych of the worthlessness and dangerousness of these kinds of rumors.

- Or that the Philadelphia PSL branch closed ranks around an abuser in a leadership position and attacked and doxxed his survivors on Twitter, or that their Washington, D.C. rally in June 2024 stymied the momentum of the spring pro-Palestine movement by engaging in theatrics when disruption was needed (setting up a bunch of tents on the National Mall and then taking them down several hours later), or that their Albuquerque branch leaders attempted to uproot the accomplishments of the Red Nation members working on the #NoDAPL campaign with habitual sexism and racism, or that they collaborate with the police before every protest, or that they deny the Tigrayan genocide, etc.

- Therapy and sobriety are themselves imperfect tools for transformation—they don’t address the problem head-on, and of course they also rely on capitalist, carceral institutions. But there is no perfect tool. We will take a few glancing swipes at the riddle of marrying a commitment to feminist principles with a Marxist/abolitionist opposition to punishment—a hot topic for sure, but not the main point of this essay. I will say that transformative justice guidebooks like Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s The Revolution Starts at Home and Incite! Women of Color Against Violence’s Creative Interventions Toolkit have a lot to offer and are more right than they are wrong.

- Franz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Press, 1963), trans. Richard Philcox, 138.

- Such as Crimethinc’s “What is Security Culture?”

- These included: low black membership, confusion about our vision and positionality (we were all afraid of being “white leftists showing up in someone else’s neighborhood,” a fear that was largely nonsense since we also lived there), confusion about the kind of work this would take (my canvass was the third one scheduled, but the first one where anyone actually showed up; after that day, it became obvious canvassing was beyond our capacity and our level of experience) and a culture of silence that made the other member feel that my writeup was totally approved of and the only way to be heard was to threaten to leave.

- Vicki Legion, “Constructive Criticism: A Handbook” (Marxists.org, 1975). The lengthy quote she uses is from W. Allen Ricket and Adele Ricket’s Prisoners of Liberation (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1973), 291-92.

- The “rectification” methods promoted by the Red Guards/CR-CPUSA will always stand out in my mind for their particular absurdity. When student member Carlos Salamanca was accused of sexual assault and emotional abuse in 2016, his accusers asked for him to be removed from the organization; Jared Roark, the Red Guards leader, ruled that he could stay after a “rectification” process that involved beating him. Scout, another member who had committed abuse, was similarly “rectified” in 2020 by being tied to a chair and beaten until he broke a rib, then forced, for several weeks, to wear a shirt where other members could freely write humiliating messages. He was not removed from leadership.

- J. Sakai, “A Talk on Security with J Sakai,” in Basic Politics of Movement Security (Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2013), 5–56.

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (New York: Vintage Books, 2009), trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier, 476.

- I am in debt to Cam W’s “Becoming a Communist” and “The Premise of Organization,” both published in Negation, for noticing this trend. His essay in this collection makes even more out of it.

- Pew Research reports that 37% of Americans have a favorable opinion on socialism as of 2022, a 5% decrease from their high of 42% in 2019.

- The Center for Strategic & International Studies’ “The Age of Mass Protests: Understanding an Escalating Global Trend,” which was published in March 2020, offers as decent an overview as any.

- “I was in a minority for hating the police. You couldn’t say it, especially in New York you couldn’t say “fuck the cops,” someone would slap you. But with Generation Z, they all hate the cops now. Or at least it’s a little bit more open.” Idris Robinson, “Race Traitors, Identity Politics, and Revolutionary Horizons Since the Uprising,” Spirit of May 28.

- “It had its beginnings in 1969 as ARPAnet, a U.S. military defense project which quickly joined cockroaches on the short list of those most likely to survive nuclear attack. Developed at the height of the Cold War, the Net had also learned from the Viet Cong, whose networks of tunnels and guerilla techniques had forced a centralized U.S. military machine to adopt unprecedented tactics of distribution and dispersal in response. These military influences on the net are betrayed in its messages’ ability to route and reroute themselves, hunting for ways round obstacles, seeking out shortcuts and hidden passages, continually requisitioning supplies and hitching as many rides as possible.” Sadie Plant, Zeros + Ones (London: Fourth Estate, 1997), 48-49.

- The numbers have stayed about steady since then, actually dropping a bit to 1.67 million (or 505 per 100,000 people) in 2020 before rising to 1.9 million in four short years.

- Angela Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2002), 58-59.

- Ibid, 48.

- Ibid, 49. Supermax prisons continue to hold about 20,000 people.

- Phil A. Neel, Hinterland (London: Reaktion Books, 2017), 69-70. Figures are about the same for 2024.

- That’s the theory, anyway. In reality, a plastic box that may or may not be a cop is about as close to a literal paper tiger as the fascists are going to give you. Uprisings never happen when the surveillance state is most prepared, and in the meantime, assembling a bloc outfit and making a map of all the police cameras in your city is always worth your time.

- Judge Daniel Paul Schreber, a respected German prosecutor whose father invented the child-disciplining “Schreber belt” used to beat baby Hitler, was institutionalized after a psychotic break in 1893 (at age 50) where the Judge discovered a shocking crisis in God’s realms: the entire Earth had been depopulated, the visages that remained were only “fleeting-improvised men,” and Schreber had been chosen by God to redeem the new world by transforming into a woman and accepting the divine seed of the new race. This Judgment Day situation was a hideously cascading result of the “soul murder” of Schreber’s soul by the soul of Fleschig, the director of the asylum. Generally, the miasmic and Satanic cosmos described by Schreber in Memoirs of My Nervous Illness bears a striking resemblance to the bureaucracies of the prison-hospital, so I find it an appropriate term to apply to the repetitive and mind-destroying prison-rituals of the Internet performed on all kinds of people but primarily on trans women and on the insane.

- Which was probably true, but in a different way than they meant it.

- Negation, for example, was obviously a product of the energy of 2020, though we definitely didn’t see ourselves as such at the time.