July 2024

Let me tell you a story. As I write these words, I am standing in solidarity with students protesting and occupying their campuses both at USC and UCLA. Having spent the last two days protesting alongside the students (as I highly encourage you to do as well), I feel the need to expedite the writing process of this particular project. Last year, I posted a video essay/documentary on the Ethiopian Revolution, particularly spending the bulk of the video discussing the student movement that precluded and lasted throughout the revolution. As I worked on the project, I got the idea to take what I had learned and write something both arguing for increased organization and protest among students in America, and taking tactics, ideas, and lessons from the Ethiopian Student Movement. Providence and present events have beaten me to the punch.

My goal now is to briefly discuss the Ethiopian student movement, and the tactics and ideas they used that we can ourselves take inspiration from in order to gain greater levels of organization and solidarity as we continue to struggle.

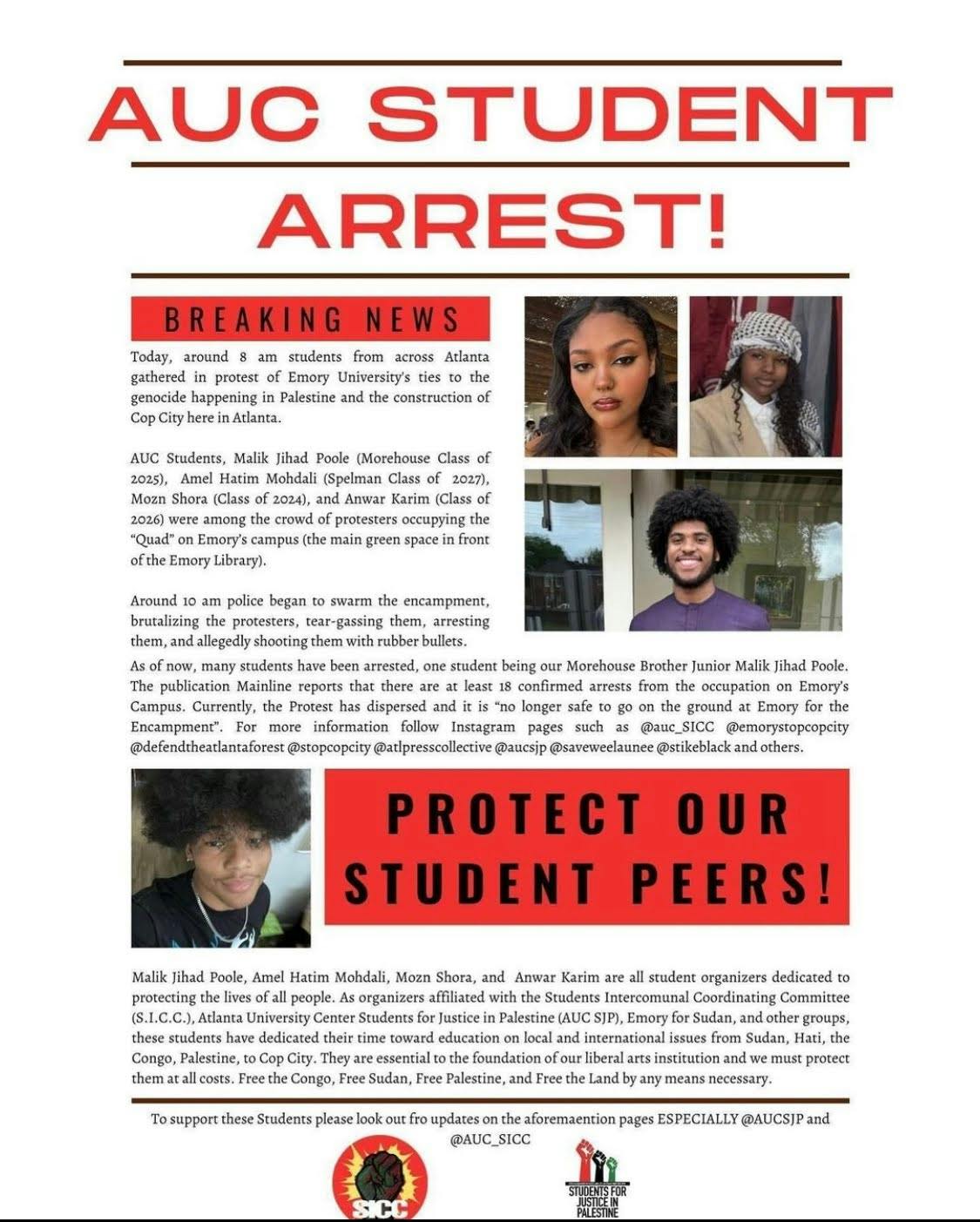

Throughout modern history, student protests have become so common that the “angry socialist college student” has become both a meme and a trope. But the ridicule of student organizers in popular culture misses and intentionally hides the power and influence student movements can have. That is what we will discuss here. The current wave of student protests in the U.S. has already begun to rival the Vietnam era protests, and bear the marks of 2020’s anti-police intifada. The shadow of Kent State’s massacre looms over all of us. As I write, snipers watch students from the rooftops of Indiana University. In Atlanta, volunteer medics are being tased and beaten while handcuffed in broad daylight, faculty daring to stand in solidarity are being brutalized and arrested in front of the students they teach. The very fingers with which I type these words ache from being smashed by police batons at USC. This violence cannot, will not, cause the movement to die down. Instead, it must cause the forging of a greater, stronger radicalism within all of us who witness such barbarism from the fascist arms of the state. It is our moral duty as Americans to materially fight and disrupt the genocide of Palestinians, and to demand the absolute dissolution of the monstrous fascist machine we understand as the Zionist state of Israel.

It is the hope of the state that by breaking up our encampments and shocking us with overwhelming and nakedly illegal violence, we will be too consumed by our fear to continue protesting.

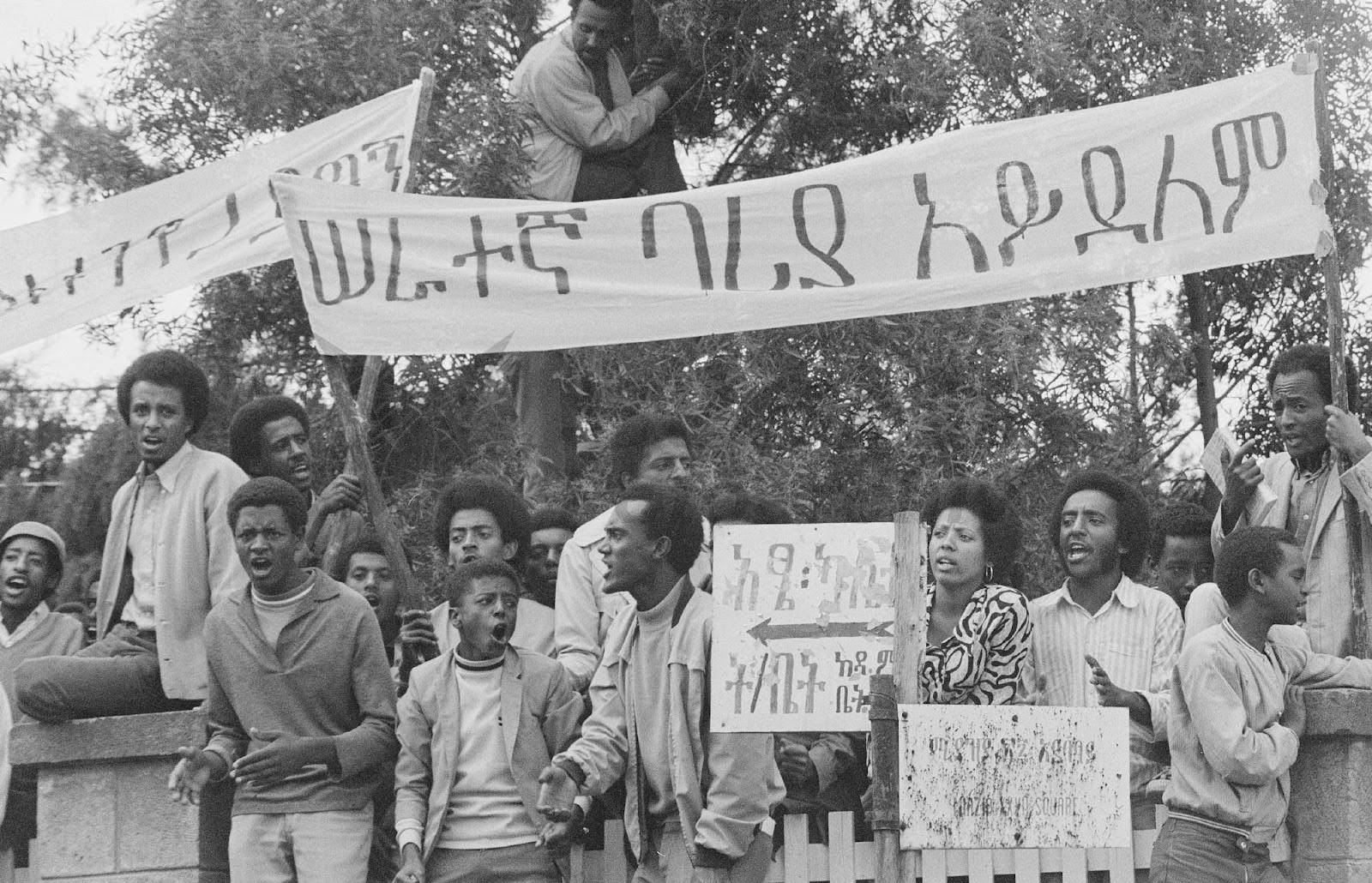

This was the mentality of one Haile Selassie, former emperor of Ethiopia, when his regime went head to head with students in running street battles in 1966. The cause of this uprising was the leaking of images from the Shola Concentration Camp to Ethiopian students. This was essentially a secret concentration camp where Ethiopia’s unhoused population was forcibly detained in Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Students protested and demonstrated against this cruelty, demanding freedom, better conditions, and the alleviation of poverty for the unhoused. The Emperor’s regime responded by tear gassing and beating students. The battle culminated at Ras Mekkonen Bridge, where students successfully resisted the police’s attempt to dissipate the protest. The police failed, and students refused to be cowed by fascist violence from bootlicking fools calling themselves “police.” The camp was later closed, and those who found themselves detained at Shola concentration camp personally went to the campus to thank the students for fighting for them. In a sense, this event is mirrored quite tragically by LA’s own struggle against the police, with the unsuccessful Echo Park uprising of 2021 being inspired by similar sentiments, followed by the incomprehensible and absurd dismantling of the DSA sub-organization Street Watch by its parent organization.

Digressions aside, Ethiopian students faced escalating methods of repression by the Ethiopian regime. In 1962, students who wrote poetry critical of the regime were berated and had their speech suppressed and subjected to checks by the regime before publication. It is vital to note that faculty who did not stand in solidarity with students acted as the first arm of state violence and repression against students, often going so far as to render students who lived on campus homeless in response to their participation in protests. Protesting students were frequently suspended, and the regime would often simply close the entire campus for all students in order to silence their resistance.

The night before I wrote this, I watched and was myself injured as police beat student protestors off USC campus and locked the whole of us out, and could not help but be reminded of these events. On my nightstand sits a 40mm foam “less lethal” round that the LAPD, a harbor for out-of-control thugs and rapists, shot at students, injuring one.

The suspensions and campus closures were not the full extent of the regime’s repression. The regime also took great legislative efforts to make student protests as toothless as possible: first, using the student union NUEUS as a peer-led site of control over the students, as well as the faculty, and second, creating new laws and regulations in the wake of the Shola Camp Uprising to control when and where students could protest. This law was set to come into effect April 11, 1967, so naturally the students set their protest against the protest bill for April 10, right before it went into effect.

The law required students to have a permit to protest seven days beforehand, to share the names and addresses of organizers with authorities, to have all signs and slogans approved, and to not have any “dangerous articles” present. A permit could be rejected on the basis of any of these violations, and violating this law could result in a 1000 dollar fine and a year in prison. For the students, this made public demonstration against Haile Selassie’s regime basically impossible, and when they protested against it on April 10, cops spent the day beating and tear gassing students into submission. There were over 120 arrests, and dozens of students reported injuries. At least fifty were hospitalized. Students responded by going on strike, refusing to go to class until their peers who remained in jail were freed.

But these fraught situations were where the unique tactics of the Ethiopian students would shine. In 1964, the regime introduced the University Service Program. This was a mandatory public service program in which students had to participate in order to graduate. 72.1 percent of participants became high school teachers, which had the supreme benefit of allowing them to communicate their radicalism directly to their younger high-school peers, providing the younger student radicals with direct inroads to the student movement on college campuses once they graduated. This both grew the student movement and meant that when college students were unable to protest due to school closures, suspensions, and mass imprisonment, the high school students could continue the struggle. It also made student rebellion that much harder to handle and suppress.

Here in the U.S., there is not so clear a pathway between college students and high school students, but one of the goals of the current wave of student protest should absolutely be building and laying bare those existing inroads so that we can propagate further radicalism and aid an already growing high school student movement that has seen walkouts across the U.S. Those students also must seek greater organizational capacity with one another. The existence of student organizations and student unions across age groups especially can aid in facilitating these inroads. That being said, we must keep in mind how student unions (such as the one on campus at USC) can be co-opted by the universities as methods of preventing and quieting student radicalism and facilitating a business-as-usual appearance.

In Ethiopia, high school students played a vital role in the student movement and revolution. They both produced theory, writing about their experiences and conditions, and participated in hardcore protests and direct actions. They did mutual aid, feeding the unhoused and poor even as they were themselves among them; they seized buses, demanding free bus fare for all, battled the police in the street, and made the revolution possible as they brought their ideas of liberation home to their parents, who themselves protested and fought against the regime that beat their children night after night for demanding liberation.

In 2020, former LAPD chief Michael Moor made the observation that the LAPD had no issue controlling a massive protest of thousands of people, but was easily overwhelmed, confused, and cowed by multiple, smaller scale protests happening in multiple locations in the same city. The students in Ethiopia weaponized similar observations, forcing the regime to play whack-a-mole as when one student uprising would be quelled, more would take their place. Student rebellion was impossible to crush as dispersed students could simply join another crowd somewhere else, would come back the next day angrier and with greater strategy and aggression, or both. The absolute solidarity between students was also invaluable. In 2020 we chanted “no good cops in a racist system, no bad protesters in a revolution” as a way of reminding ourselves not to police each other's resistance, to stay in solidarity with each other, and never trust the police. In Ethiopia, the student rebellions were at their weakest and most vulnerable when students allowed themselves to lose sight of their material goals and demands and argued instead among each other. This allowed the regime to exploit those political divides, fueled partly by the paranoia of traumatized students. This is why an insistence on respecting a diversity of tactics and radical ideas within reason is not only necessary, but required.

Another important piece of the student movement's success was the support and aid of the faculty. During a police attack on a permitted protest at Arat Kilo campus, faculty found themselves also falling to police batons and violence. The faculty’s pressure against the government, especially via the EUTA (the teachers association), was an invaluable voice against the regime’s suppression of student radicalism. They both participated in student protests at times, and also demanded the release of their students from jail when arrested and brought to light the destruction of their campuses and teaching materials by police. In the modern day, there is a severe marked difference between the success of student occupations that do and do not have faculty support. This relationship is symbiotic. Students support striking teachers and teachers must support protesting students. This kind of solidarity is what made protests 75,000 strong able to march through Addis Ababa to topple the regime. Nine schools had to close as students had both refused to come to class, and continued to disrupt ongoing classes. A police report of the time alleges that 2,775 were detained, 377 were charged with crimes, and 60 people were charged for supporting the student movement, and that two students died.

The student movement was not without its martyrs. As things escalated, a number of students fell to the regime’s violence. Shiferaw Kebede was the first. The high school student was killed during a protest demanding the waiving of school fees, improvement of conditions, and an end to arbitrary suspensions, when police suppressed the protest violently. Another martyr, Demeke Zewde, was killed after falling from a police van, as students attempted to stop a police transport that had been kidnapping students off the street to take to police training centers to be detained. Yet another, Takkele Welde Hawaryat, died fighting cops that November. The most famous of the students killed was the prominent student organizer Tilahun Gizaw. Tilahun was among the first of few students to advocate for and aid feminist student women in gaining prominence in the movement and organizing, and his death was believed to be an assassination by the state due to his influence.

On Sunday, December 28th, 1969, while out on a date with his girlfriend at Afincho Bar in Addis Ababa, two men approached Tilahun Gizaw and shot him three times. The shooter was later identified as police officer Berhanu Mecha. Tilahun himself was taken to Haile Selassie Hospital, where he died of his wounds before he could be operated on. Students took his body to the medical facility on the main campus to be autopsied there, and an upswell of student activity began brewing, as students gathered en masse at Sidist Kilo campus the next day. By 12pm Monday, over 1500 students had gathered, carrying signs condemning the murder of Tilahun Gizaw. When police later arrived at the campus to retrieve his body in order to bring it to his half sister, another conflict ensued, as the students had their own plans to hold a procession and take the body to his father’s house.

Tilahun Gizaw

“Around 2:45 PM, the Bodyguard unit filed into the campus, took a position behind the assembled students, and then charged with bayonets fixed. There was shooting, originating from students according to the police report, but the only dead and wounded were students. The final tally had three students dead: Sibhatu Wubneh (a second year law student who was apparently chanting slogans over a megaphone at the time). Jemal Hassen (a second year arts student) and Abebe Berhe (a freshman in the physical science stream). Sixteen students were wounded. Also wounded on both legs was a Polish political science professor, Professor Szuldrynski, ironically very much a supporter of the regime.

The military force managed to snatch away the body and hand it over to the police, who were waiting outside the gate, and the body was carried in an ambulance to the outskirts of the city for immediate transport to Tilahun’s birthplace in Maichew (southern Tigray), where it was buried on Tuesday 30 December in the presence of some five hundred people, including his half sister and the governor of the province Ras Mengesha Seyoum.”

- Bahru Zewde, “The Quest for Socialist Utopia”

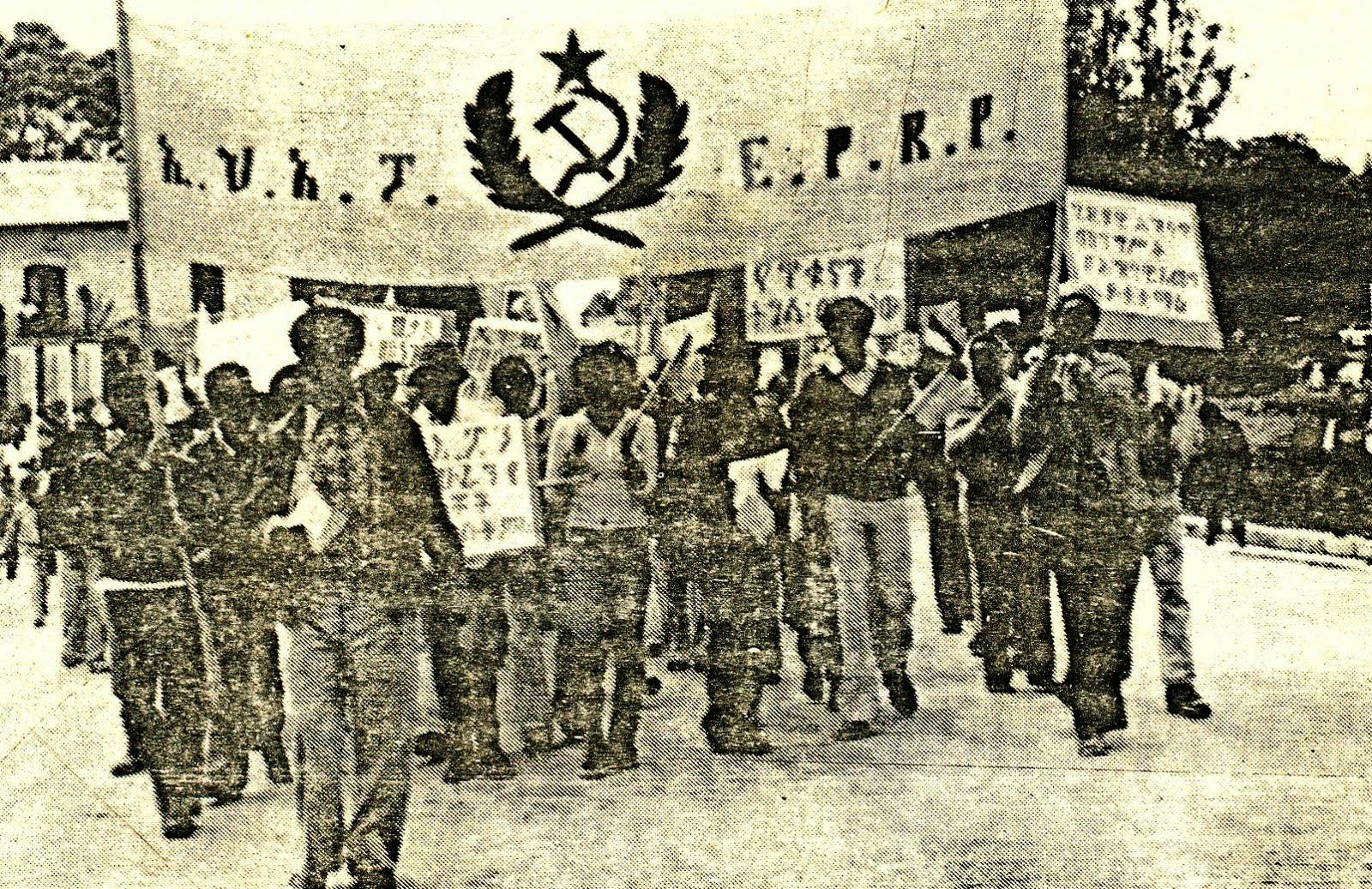

In the end, twenty seven student organizers were identified and arrested, and the students and faculty were left in chaos. The faculty were particularly frustrated with the situation as they had their own staff injured by police as well as students, and had not been aware the raid was going to happen. This was in addition to the significant amount of school property destroyed by cops. The student response was delayed by the fact that many were left unsure what to do. Student unions were banned, as were publications, leaving few avenues for struggle. Some opted to leave Ethiopia in exodus, some refused to boycott classes and returned to normalcy hoping for an end to the violence, and others began seriously discussing the continuation of struggle in a more militant form. Such continuations are beyond the scope of this essay. Instead, we will discuss a methodology of resistance.

I feel it almost need not be said, but if there are campuses near you being occupied and you are a student, I highly encourage you to participate; if you aren't a student, check and see if students are asking for solidarity and participation from non-students (some have done the opposite for safety reasons) and go participate as well. If you have the resources to bring food, water, tents, palettes for building barricades, do so.

If there is not presently an occupation on your campus or other form of protest, consider taking the steps to create it yourself. I understand that this is intimidating, but remember always: if you build it, they will come. There are like-minded students among you likely waiting for someone to give them a clear step toward resistance. Students at Columbia University were only able to confirm sixty students as participating in the occupation protest, far short of their goal of two hundred, but that didn’t stop them, and their numbers grew far beyond expectation.

By now, many of these encampments have been swept and replaced, or in some cases such as UCLA, seen students continue to engage in other forms of struggle post-sweep. It is important to remember as things develop and situations change, to be fluid and capable of responding to a multitude of conditions. We must strike when the enemy is weak and retract when they are strong, explore ways of disrupting while avoiding direct confrontation with police, and continue our fight even as we are repressed.

One of the first steps one should take is forming an affinity group of like-minded students whom you know you can trust, and building your occupation or protest from there. Delegate tasks among yourselves, each according to ability and need. Another vital step is ensuring that your occupation has a well-stocked medical tent, with experienced/trained street medics who can administer aid in the case of injury, or the deployment of chemical weapons such as tear gas and pepper spray. As numbers swell, like-minded community members and non-students may also find their place among the movement, bringing experience, resources, and manpower, and helping to spread the movement to a wider base. If there is a local collective that provides jail support to arrested protestors, get in contact with them. If there is not, work among your comrades to develop a strategy of jail support and delegate that aspect of organizing to a specific wing. It may also behoove you to develop some method of vetting students and participants who come to the encampment. At UCLA, student organizers mark each participant who enters the occupation zone with a marker on their arm to display when before entering. This is highly effective, though I did have a brief humorous exchange when attempting to reenter the camp where I informed the organizers that their chosen color does not show up well on dark skin, and that should be accounted for.

I want to leave you with a final reminder to continue to struggle, that if one mode becomes untenable, we must seek other ways to continue to be disruptive. We must adapt to the tactics of repression in order to continue struggling.

We stand in the presence of a situation with near-limitless potential. What happens on these campuses now will define the rest of this year, and all signs point toward a hot summer. Unlike the summer of 2020, we are ready. We have spent the last four years developing our skills, strengths, political analysis, and connections as comrades, and now is the time to display the fruits of that labor. Occupy every campus and every building, spread our rebellion among our parents, our siblings, the high schools, colleges, and community centers. Our fight against American imperialism and Israeli Zionist fascism is not over, and when we fight, we win.

Sources/Recommended Reading:

The Siege of the Third Precinct in Minneapolis

"It Is an Honor to Be Suspended for Palestine"

A Demonstrator's Guide to Understanding Police Batons

A Demonstrator's Guide to Understanding Riot Munitions

A Demonstrator's Guide to Gas Masks and Goggles

Protocols for Common Injuries from Police Weapons

Campus Building Occupations, 2008-2010 and Today

Horst, Ian Scott. Like Ho Chi Minh, Like Che Guevara: The Revolutionary Left in Ethiopia, 1969-1979. Paris: Foreign Languages Press, 2020.

Zeleke, Elleni Centime. Ethiopia In Theory: Revolution and Knowledge Production, 1964-2016. Chicago, US: Haymarket, 2020.

Zewde, Bahru. The Quest for Socialist Utopia: The Ethiopian Student Movement, c. 1960-1974. Suffolk, UK: James Currey, 2017.