April 2023

Content warning: Pornography.

“His prophetic energy is so disproportionate to his imagination as to produce not horrors but a game of forfeits and very high numbers, metaphysical farce, Rube Goldberg assembling the atomic bomb…”

— Marvin Murdick, “Must We Burn Mme. de Beauvoir?”

I. Sex and Death

Art is answerable to the world, to ethics, and to politics. But to understand art in terms of censorship, self-expression, critique, or interpretation is to dismember all its real functions as art. Art is affect. Art is surface. Art is pleasure. Art is endorsement. Depiction is endorsement; this fact is so true it’s tautological. We wish to cut into a piece of art, to redeem it with a clever interpretation or contain it with a stern rebuttal. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise, and at the end of our critique we find we have only cast more art at our feet atop the original.

Art has nothing to fear from the world of decency; it rules the world of decency and the implications of every decent action. “The key is not in what is forbidden but what is sanctioned, really and truly sanctioned.”1 Pornography lies about human nature, but it shows off misogyny, heterosexualism, colonialism, and violence with the butcher’s honesty. The difference between Pocahontas and Custer’s Revenge is the difference between the Burger King ad and the tour of the slaughterhouse.

This hardly redeems porn; in fact, it suggests porn is worthless except as a historical document. But to the extent this is true, it’s also true of art in general, which can only know the world; as far as it explores it only finds more world. Each new work of art is exciting because it knows the world in new contours, and if it indulges in craft and symbolism, it does so only because it seeks the world with new greed. The key is not in how art lies but in how it tells the truth. Symbols are always brusque and obvious: the game you play (as an artist, critic, consumer) to feel the way you feel is the only “symbol” the work requires. There are no authorial cues, no intentions, only the cultural machine stamping away at paper and film the same way it stamps onto human bodies. What do Martin Scorcese’s feminist pretensions mean to the teenage boy (or grown man) beating off to Jodie Foster in Taxi Driver?

Art can only know the world by means of leaving it. It is always fantasy. It can’t instruct in the manner of lived experience. When a story ends, it spares us from consequences. If we don’t like how it ended, we can start it again and enjoy it all from the beginning. In reality things only matter because they keep going. When something dies it may keep going in another form, and it may well tidy up and become a story — subtle hints, one-night-stands, declarations of love all played back to front over and over again and recut and embellished and flitting about our present day in metallic traces like the sonic disease from space playing plundered love songs over the sex scenes in The Ticket That Exploded. It doesn’t mean anything or it could mean anything, and eventually, relayed enough times, it dies for real.

If the pleasure of sex (to make Simone de Beauvoir nasty, brutish and short) is the pleasure of dissolving into another person and losing for a moment your pitiful life in the ecstasy of action, then the ugly denouement (post-nut clarity) is the recollection that sex is just another event in that life. Pornography spares us this horror when it leaves us alone in the bedroom. All the real fun of sex is absent, but so is the confusion of making your way with another human being. If the text were to summon anything more like a human being, that would dampen the experience, which is why pornographic apparitions are always so happy to clean up and leave.

Beauvoir says that sex would be better if it killed the woman at the end.2 The draw of porn and of art in general is that it does the killing for us. Sade’s libertines take to murder and inhumanity with insatiable creativity in their quest for a sexual experience that leaves them alone; Sade’s readers are spared the trouble.

Justin, the Jeffrey Dahmer stand-in in Poppy Z. Brite’s “Self-Made Man” (“I just had to get the Dahmer-mania,” Brite says in his introduction, “out of my system”), picks up quickly on the connection between a book and a murdered body: “In the world of the story, no one left before it was time. Characters in a book never went away; all you had to do was open the book again and there they’d be, right where you left them.”3 Justin’s lovers are still stuck in his apartment, invisible, like dirty magazines and masturbatory memories, “their organs wrapped neatly in plastic film, their hands tucked within easy reach under his mattress, their skulls nestled in a box in the closet.”4 Of course in time even bodies decompose, and “the most passionate images are cold compared with real sensation.”5 If he’d never had them at all he would probably get along fine, but as is, knowing there’s something to prolong, he hunts, like Dahmer, for a “homemade zombie,” a lobotomized sex slave “who lived and stayed with him, whose mind belonged to him.”6 Force is too manual, manipulation too social; a proper sexual victim would do what you want simply because there’s nothing left of them beyond your will.

Justin’s victim tonight is Suko, who hits all the classics of Brite’s oeuvre — a racialized and sexualized man, 19, Thai, “a raven-haired heartbreaker,” “fingers the color of sandalwood,” eyes daubed with “stolen drugstore kohl,” dressed up like a Halloween doll in “torn black cotton” and protective amulets strung on leather thongs, listening to a poor-quality Bangkok bootleg of the Cure given to him by his hometown sweetheart, Noy — a “jaded, fiercely erotic, selfish boy” who worked the brothels with Suko, and whom Suko ultimately dumped to pursue a better life in America. Suko recalls their romance with heat and bitterness. Of their sex tourist clients, he mostly recalls the “range of body types” — “fat or emaciated, squat or ponderously tall, ugly, handsome, or forgettable. All the Thai boys he knew were lean, light brown, small-boned and smooth-skinned, with sweet androgynous faces. So was he.”

He gets picked up by Justin at a bar — one might expect him to be turning a trick, from what we know about him, but he’s just looking for fun. He catches himself on his English — “why you don’t,” sorry, “why don’t you;” a clumsy “hey, no problem” chosen over “mai pen rai.” It should be noted that kohl is a cosmetic predominant in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia as far east as India — not Thailand. But these little surprises are not the soul of any work. For all we know the kohl has more to do with his love of the Cure than his spirituality. The key question in character analysis is always: what kind of hole was made in Suko? Is it a hole big enough for a person? Who or what will creep through? Angela Carter notes that pornography always leaves in itself a reader-avatar — “the text has a gap left in it on purpose so that the reader may, in imagination, step inside it.”7 Suko’s inaccuracies and flops of characterization could be the means by which we experience him, envy him, judge him, and get high on him — instead, I’d say he seems nice enough but I hardly got to know him. But somewhat surprisingly, it’s equally hard to imagine stepping inside Justin, who seems like little more than a scared child with some surprising capabilities — Dahmer himself wouldn’t have much interest in a line like “He didn’t remember meeting the boy, didn’t know how he had killed him or opened his body like a big wet Christmas present.” This impenetrable quality is the means by which Brite crosses over from pornography into proper trash literature.

My analysis focuses on literary erotica (“the pornography of the elite”)8, gay porn, and counterculture porn mostly because to get a map of the terrain, you need to know where the terrain turns over into something else, and vice versa. An essay on objectification and the commodification of sex that focuses on Pornhub and other mainstream content would more or less write itself. Plus, it would still be perforate with all the caveats you have to make when critiquing a whole mode of expression as if it’s one work. “Playboy is Them — no doubt Kissinger and Sinatra sleep with it tucked under the pillow. But the counter-culture sex papers are created by people who inhabit our world…, people who share our values, our concerns — people who talk of liberation.”9

This is a work of literary criticism, but my objective is not to gossip about a few pieces or drum up evidence that porn was “liberatory all along” (or “oppressive all along,” or “oppressive but holding some counter-hegemonic strains,” blah blah blah). If you’re a Communist (or a halfway-decent feminist) you understand that nothing is necessary or predetermined and that the point of good analysis is to change the world, not observe it. Any analysis can be a materialist analysis if, and only if, it takes its aim at the task of intervention and takes that task seriously.

II. Materialist History

Women have been conceived of as a class — that half of the human race consigned by society to reproductive labor. “Reproductive labor” can seem like a seedy reference to the reproductive capacities of cis women.10 But besides being that, it refers to the day-to-day tasks of reproducing the world, of making it fit for use again tomorrow: scrubbing the toilets and washing the sheets, changing diapers and putting on shirts, cooking, sewing patches, etc.

Beauvoir referred to this as “immanent” labor, in contrast to the “transcendent” labor of the productive man.11 The Male goes out into the wild, conquers, kills, invents, creates, discovers, breaks boundaries, “transcends” the drudgery of the human species by reshaping Nature into something wholly new. The Female embodies the drudgery: she sits at home, in the dark, knitting and knitting, day after day until the whole world winds down.

Much of household labor is unpaid: it stands outside the realm of counted-for economy, and falls, in Marx’s schema, “to criminal law, to doctors, to religion, to the statistical tables, to politics and to the poorhouse overseer.”12 In this way Marx’s tendency to use “man” and “human” interchangeably was no 19th century oversight. Women can be found in Marx’s description of the spider, ant, and beaver: weaving the same web every morning and tearing it up every night, producing “only itself,” “only what it immediately needs for itself or its young,” “only under the dominion of immediate physical need.”13

These designations are descriptive designations, not practical ones. Class designations are practical: you are a worker to the very same extent that you sell your labor-power to survive. If it’s debatable whether someone is a worker, that’s because it’s debatable whether they sell their labor-power to survive. But we all know women who can’t or won’t have kids; we all know women who have atypical household roles; yet it is plain as day that they are women.

Part of the problem is that there is in fact no difference between production and reproduction or between transcendence and immanence. They are just different angles taken on the same process. Beauvoir recognizes as much:

Thus paternalism that calls for woman to stay at home defines her as sentiment, interiority, and immanence; in fact, every existent is simultaneously immanence and transcendence; when he [sic] is offered no goal, or is prevented from reaching any goal, or denied the victory of it, his transcendence falls uselessly into the past, that is, it falls into immanence.14

Even victory falls into the past, and becomes immanence. Everyone dies poor; everyone dies ignorant; everyone dies an animal; everyone dies alone.

And transcendence is inseparable from the immanence that sets its stage, even before it becomes the stage. The first computer was a Jacquard loom with improvements.15 The Industrial Revolution is inconceivable without the proletarianization of women: assembly-line machines require a body of laborers willing to make the same repetitive motion 14 hours a day for the sake of shirts. The Great Achievements of society are but the meekest variations on that titanic theme comprising all the rote, repetitive, unstoried, undignified work that keeps us all alive.

This is not to say that all work is women’s work or that laundering underwear is What Truly Matters or anything so pandering: “everything is immanent” is only as true as “everything is transcendent.” The point is that these designations are themselves gender designations and their so-called coherence is a part of the patriarchal division of labor.

Which is why these divisions can be recast so easily anywhere, any room with both a man and a woman in it: the CEO and his secretary both drive to work, both participate in traditional political economy, both have a means of subsistence completely unrelated to the family, but still play out the same heterosexual role — the man still forges the path, makes the big decisions for the company, and announces new ventures, and the woman still performs the dull work of upkeep, the transcribing, the rote calculation, etc.

Men and women are Images, hanging ghosts in the air, faces painted on the wall, masks no face can enter, the rules of a game getting explained over and over again to everyone and getting explained by getting played. They are images, but they are not immaterial (nothing is immaterial): they determine who produces what, who lives what life, who is punished for breaking what rules, who can be raped with impunity, who can be beaten with impunity, who can be killed with impunity.

This can sound like petty nuance or playing with definitions. But it makes all the difference in the world once you start planning political action. If Man and Woman are strictly class designations denoting one’s role in the process of (re)production, then the solution to patriarchy is simply the integration of women into the traditionally-male political economy (followed if you please by socialism). Erase the whiteboard and write out every task again, and split them up fair this time: you can’t make it happen in each house individually, but you can make it happen in the broader economy and things should fill in from there.16

This logic is what enabled the USSR under Stalin to declare it had abolished the family while releasing edicts banning abortion, suppressing divorce, and recommending women to wear more makeup and look pretty for their husbands.17 Women “as a class” had been abolished, because they made the same wages as men, sat on the same councils as men, and reached the upper echelons of administrative power previously restricted to men. Those laws that seemed to tug women back to the realm of immanence attacked only women-as-Image (woman as whore, woman as mother, woman as trickster, woman as divine grace), and Images are immaterial.

The USA imported this model with American flair in the 1970’s. Capitalism has mined greater swathes of women for its proletariat for as long as it has existed, but a shift in norms in higher education (propelled in part by a rejuvenated feminist movement post-1968) meant women found it easier than ever to get professional jobs, make breadwinner wages, reach positions of influence, become owners and bosses, and even wield political power. This brought new dignity to women in certain social strata, and greatly transformed the face of gender relations as a whole, but it also saturated the feminist movement in the long run. Of course not all women can make enough money to escape the strictures and abuse of familial relations — the math doesn’t work out that way — but some can. “To be a woman is to be automatically at a disadvantage in a man’s world, just like being poor, but to be a woman is a more easily remedied condition.”18 Women interested in a better life have every reason to focus on their own misadventures rather than the lot of women as a whole.

If you are a woman, and you feel trapped, hated, nameless, and exploited, and you want to be loved, cherished, comfortable, powerful, and free, you no longer have to bother worrying about collective liberation — you can do it yourself. You just need to take advantage of your opportunities. You just need hard work, thrift, and a little luck and soon enough, you’ll have more than enough money to live how you want without being subservient to anyone.

It’d be idiotic to say that workplace equality served a regressive role or to summon some tortured “girlboss” icon to place the moral onus on professional women. We can make a crude metaphor to fugitive slaves, whom W. E. B. Du Bois describes as “the safety valve that kept down the chance of insurrection in the South.”19 Obviously Du Bois is not accusing fugitive slaves of betraying some hypothetical antebellum revolution, or condemning, as reformism, the collusion among slaves and abolitionists that made escape a viable route. He is simply noting that, absent this mechanism (which could logically only free a minority of slaves), black slaves would have had no choice but to band together and violently overthrow their oppressors (as they did in, say, Haiti). There are telling differences, however. A slave escaping the plantation is immediately putting their own life in danger and making an enemy of the law, the cops, property relations, and white society; a woman who chooses to pursue a career is not (race, of course, is still a massive part of the equation, and assimilation into professional circles is a far more antagonistic process for black women than for white women). Slavery is naked oppression; womanhood is mystified oppression. Most illustratively, slavers made a point of ripping apart slave families.20 Submission to one’s role under patriarchy is how a woman finds a family! A fugitive slave could not realistically climb to a position higher than “worker.” Black people in antebellum America who did try to amass wealth and embark on capitalist projects were invariably “driven back into the mass by racial prejudice before they had reached a permanent foothold.”21 But everyone can name woman landlords, woman bosses, woman cops, woman politicians, etc. All this adds up to an escaped slave who by default “knew that he was not free until all Negroes were free” and who put his new power and freedom into efforts to hasten abolition, culminating ultimately in the Civil War.22 It would be quite hard — impossible in fact — to narrativize feminist gains of the past 50 years as any kind of prelude to a Civil War; they have been absolutely meager — and yes, the Kamalas and Hillarys and Ghislaines of the world have been traitors to women everywhere. “A free woman in an unfree society will be a monster.”23

It is this crisis moreso than the so-called sexual revolution that prompted the feminist sex wars of the 1970’s. Every smart feminist could see that economic integration was not a means for transforming the way men and women behaved toward each other. So the new question became “What is the proper vector of change for us feminists?” The answer generally hovered around transforming the image of women by taking control of the institutions that propagated this image (psychology, education, the church, the arts, pornography, etc.). Woman is, at base, an image; that’s the only way in which “woman” can be meaningfully described as a class — the class of people who produce the image of woman through its inscription upon them.

Unfortunately, taking control of a cultural institution is more easily said than done. Even once you’ve picked the means to your ends, you’re liable to spend the rest of your life pursuing new means to get the means and endlessly complicating the issue — this is what struggle is. The means of intervention put forth by anti-porn feminists like Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon eschewed revolution for legalist reform and eschewed class struggle for a liberal conception of political advocacy — Dworkin pursued an alliance with the police, the prison and conservative American culture, and so it’s no mystery why feminists in the 21st century largely either turned her aside or retired to outright reaction. But the libertarian feminism that opposed her has been just as apt to stymy and depoliticize.

To talk about art and ideology is to throw yourself back into this debate, tacitly or not, and so I’m hardly done with Dworkin or the other creatures of the 70’s. In the meantime, it seems fruitless to detail the image of woman without first defining what images are, how they change people, and how they can be changed.

III. The Machine Upon the Body

An Image is an abstract machine: the rules of a game getting explained over and over again and getting explained by getting played.24 These rules can manifest as literal rules blocking you from doing what you want, but they can also structure what you want before you ever think about it: they can be the most primitive, natural, unutterable interests of yours, written in the sky, written in the smallest chamber of your heart. Break the rules and you get punished; follow the rules and you win the game, which is very exciting in the moment, but of course the game is just a game, and now that it’s over, you have to clean up.

Gender is an Image, and the expectations set by gender of what to do and how to look are the rules of the game, played again and again. Specific archetypes of Man and Woman (the Whore, the Mother, the Stoner, the Intellectual, etc.) are also Images with given rules that attract or repel. Genres are Images and the tropes of the genres are rules of the game.

The rules of a game obviously determine with unerring accuracy the modal tendencies of the games en masse — in well over 99% of chess games the bishops are moving diagonal, the pawns moving forward, et cetera. But on a molecular level, they are just rules to a game and you can break them anytime. Breaking the rules doesn’t become a point of intervention unless instrumentalized for a more collective revolt — otherwise, it changes only your own life, and only for right now. Moreover, you don’t want to break the rules all the time — you live not as a player but on an intoxicating racetrack dance of player and pawn, actor and role — you can be a player on one game and a role in another, let loose from one abstract machine and all affray on the treads of a new one you’d never known existed and so on until you die.

What is the relationship between actor and role? A common conclusion in the culture war today is that it’s unfair to conflate a character with the artist who created them. But if a character is not an accurate portrayal of the artist, it’s unlikely that the artist has made an even halfway-decent portrayal of the character. This is true across all meanings of “portrayal” and all artistic valuations. Consider this anecdote from Peking Opera and Mei Lanfang:

A story is current that in a certain city in Italy there was an actor who was famous at playing the villain. Once in Othello, he played Iago so well that he aroused so much anger and hatred among the audience that one spectator raised a gun and shot him dead right on the stage. As a token of homage to this famous actor, the city built a fine tomb for him. One day, Stanislavsky happened to pass by and on hearing the story, decided to erect a tombstone in honor of the poor actor with the inscription: “To so-and-so, the best actor in the world.” A few years later, Brecht happened to pass by the same place, [and] he too decided to erect a tombstone standing side-by-side with that of Stanislavsky’s with the inscription: “To so-and-so, the worst actor in the world.”25

The amount of distance that the actor, writer, or artist draws between themself and their subject depends on the standards of the genre. But the relationship is always a portrayal and the portrayal always runs both ways.

The trouble with the Iago situation is that “actor and character merged into one.”26 The man became Iago and had to be dealt with the way Iago should be dealt with. The same process occurs for porn stars; but they merge into the actor, not the character. Riley Reid is of the Brechtian school when it comes to playing stepsisters, coworkers, therapists, etc., but of the Stanislavsky school when it comes to playing Riley Reid. Because Riley Reid is not real, any more than a Starbucks barista is real — when she puts her star sign and Interested In in her Pornhub profile this is an outstretched performance of the kind all service work involves, a performative declaration that Love has won the day, the porn star really does want your cock, the barista really does love to see you in the morning, even before money has anything to do with it.

Former camgirl Aella Girl (now better known for things like racist Twitter polls) published a 2018 guide on camming where the most consistent advice is to cam like you aren’t camming at all. Your space should be a bedroom, not a studio. You should look like not a porn star but the girl next door who rolled out of bed and came up with this on a whim — croptops and eyeshadow, not lipstick and garters. Most importantly you should look wealthy, of independent means — you’re not going to get big tips if any tip would make a difference. “Make Them Forget This Is About Money,” reads one heading:

Never refer to tokens as money!! Refer to tokens as little as you can while still being clear. One of my camgirl friends would use the technique where she’d say, “This is like – I’m sitting at a bar, all alone over here. Is someone gonna be a gentleman and get me a drink?” And then someone would tip and she’d drink.

You’ll never have the guts to shoot Iago — but you’d take Desdemona out for drinks, surely, if the actress looked at you just the right way! The audience is swept along, this is the real world, this is casual, this is how casual sex happens, money, a drink, a disparaging remark. “Work, in this context, is really dirty work; it is unmentionable.”27

Let’s retreat a little ways, to the Golden Age of Porn, and investigate Fred Gormley’s inspired performance as putative porn star Michael Flent, performing as the Emperor in 1981’s Centurians of Rome [sic], a sly, made-up, high-femme narcissist gay of the type that has fared better into the 21st century than the musclemen surrounding him:

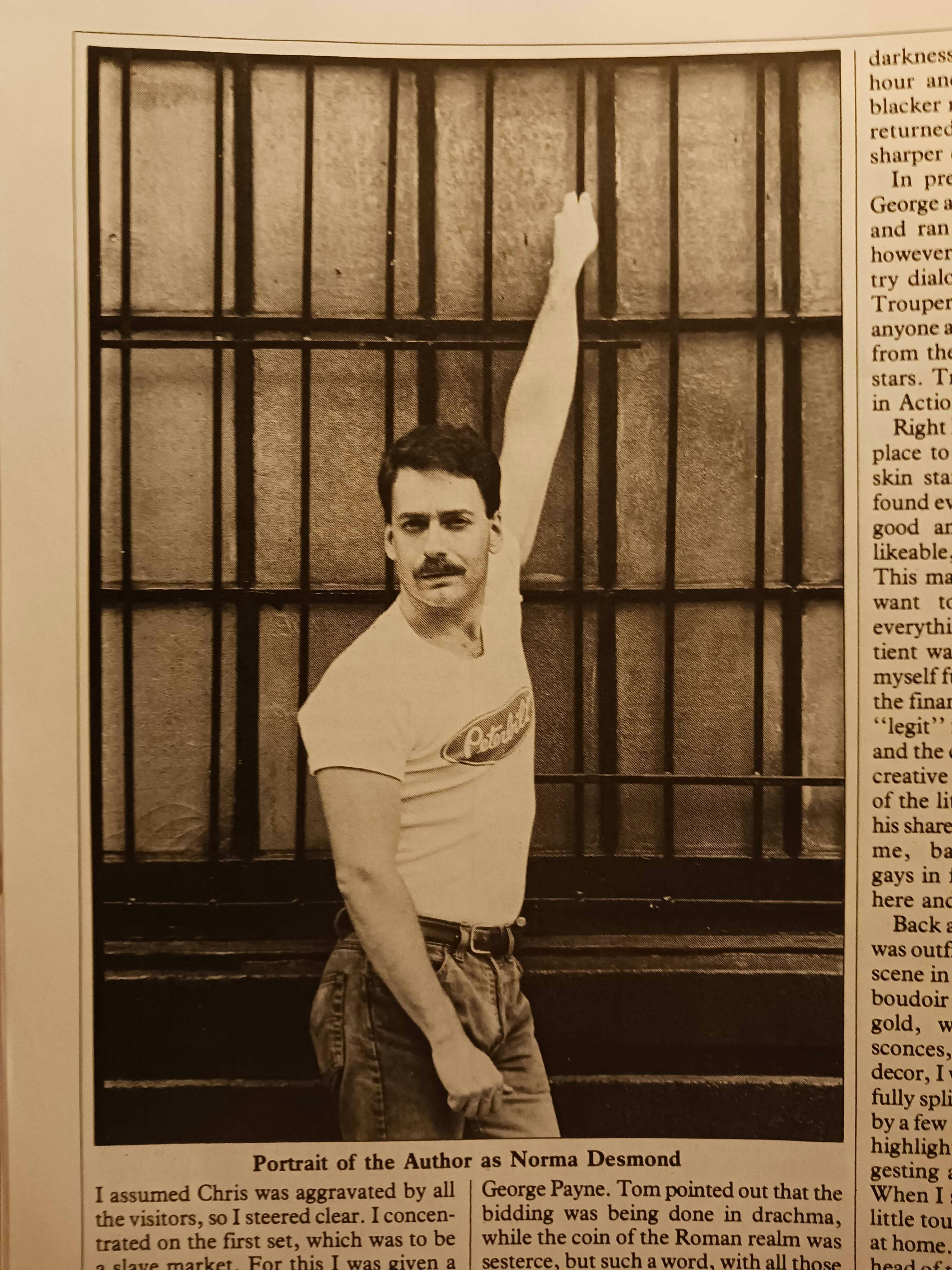

Fred in person looks more like a regular guy, sort of an otter. Here he is photographed in his tell-all account from Christopher Street from 1984:

Fred suggests his more “regular” look ultimately obstructed him from further roles in porn after this debut: “My eyes said that I had lived beyond innocence and I couldn’t play twinkies. My body wasn’t massive enough and I wasn’t craggy enough for the heavy-duty stuff.” But people liked him in Centurians: he went back to watch it several times at the 55th Street Playhouse in Manhattan, and the Emperor’s appearance brought on stirs, meows, and calls of “My God! It’s Joan Crawford!”

Guys line the theater cruising the audience watching the film. When I came on, they’d see me up there, then they’d see me down there, then back to the screen, then to my seat. Consistently triple-takes, like a tennis match. One time I went to the room behind the screen and, while engaged with a gentleman from Florida, heard myself come onscreen. Why didn’t I go for it — run in front of the projector and do a live version of “We had faces then?” I don’t know. Life is filled with such missed opportunities.28

The Emperor stares in his reflection, in his bedchamber (actually a gay sex loft on 23rd Street, but done up in the Roman way), considering his fiat, his “riches, slaves and friends,” his territories, his “secret peccadilloes,” his “naughty, naughty lust,” all shards of a man with the splendor of the sun — next Saturnalia, he will burn a portrait of himself so that Heaven can receive a beauty like his. This speech becomes an obstacle course for the actor, who’d already “popped in my medicine” and suddenly needed to remember fresh lines crammed in at the last minute by on-set busybodies while winding around with a mirror before a tracking shot that can never catch sight or glare of itself. Then the slave Demetrius (brunette, fit, played by era icon George Payne) shows up, fulfilling the film’s most longwinded joke: Demetrius has for the past 20 minutes of screen time been getting “trained” to submit to the emperor, taught to never cross his arms or legs, taught to accept everything the Emperor does to him, fucked in all sorts of creative ways, etc., but there’s been some sort of mixup because — what do you know — the Emperor’s a bottom! Demetrius fucks and fists the Emperor for four hours, taking breaks irregularly so that Fred Gormley’s ass can be cleaned up and re-larded and the camera can prepare another angle. George Payne’s cumshot lands in the film, but Fred’s, on account of bad timing or bad camera work, doesn’t. “After a week of self denial, my art was not to be immortalized. I harrumphed off the set.”29

Filming wraps after 3 days with a press party at the Underground disco. Michael Flent is “in total ecstasy.” Early buzz calls him “a discovery” and the best thing in the film. Later the director, cruelly, will tell him he’s “not a star.” His promotion work for the film will go largely pro bono. New expenses will force him to move from the Village to a shared apartment in Chelsea. A hack job film editor will hand in “a cut that was so rough pieces were missing and never found again,” and the final film will be wrinkled, revised, abridged. Brian, the co-producer, will turn out to be “the proprietor of Manhattan’s biggest call-boy operation” and Jay, the other co-producer, will turn out to be the pseudonym of George Bosque, a Brink’s security guard who in 1980 commandeered a truck and stole $1.5 million which he used to finance Centurians of Rome (among other extravagances).30 George Bosque will be captured in San Francisco in August of 1980, just days after meeting with Fred, the director and the other stars at a Benihana’s and clandestinely arranging a new deal that cuts Brian out of the profits. He will be sentenced in 1982 to 15 years in prison. In 1986, he will be released. In 1991, he will die. Rights to the film will fall to Lloyd’s of London, the truck’s insurer, after a lengthy legal battle. The film will make a profit — double its $100,000 budget, which will be the highest budget of any gay porno film until 2008. Fred Gormley will write many more pieces for Christopher Street, write three off-Broadway plays (American Lesion, Fun with Death, and The Night Larry Kramer Slapped Me Really Hard), continue to work tirelessly for gay rights (eventually as an AIDS activist), and die in 2002 after a fourteen-year struggle with HIV/AIDS.31 But Michael Flent is only alive for tonight. He glides effortlessly atop the world. He has no need for money or other human concerns. He is life divorced from need, from production, and from death (though he will be gone soon). He wants only love and endless play. He wants only your cock. He is a burning effigy for Heaven. He is the hanging ghost in the theater as the eyes flit from the screen, to Fred Gormley in his chair, back to the screen again.

IV. Art as Surface

Porn is a mass art — it was born in print with the printing press, in image with the photograph, in sound with vinyl, in motion with film, etc. The Venus of Willendorf was no more “pornographic” than a naughty Polaroid stuffed in the trunk of a couple’s attic.

In “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility,” Walter Benjamin draws a distinction between cultic art (which has ritual, devotional, contemplative value) and mass art (which has a collective, habitual, political value). When you knit your friend a nice hat and give it to them for their birthday, the value is the ritual. Benjamin is explicit that this ritual is magical, it serves “magical practice.”32 Constructing the hat is a ritual: you refresh and consummate the friendship, you show the friend you care. Wearing the hat is a ritual: you think of your friend and certain memories erupt to the surface, and go out into the world in a new light. Admiring the hat is a ritual: every stitch becomes a point of devotion, because this hat was made for you, with love: you are in the most serious sense a part of that hat, a critical fact of its existence, “absorbed by it… just as, according to legend, a Chinese painter entered his completed painting while beholding it.”33 All this is specific to the “aura” of the hat, which is Benjamin’s word for its place-and-time, its existence as a specific object. No other hat will do. If you lose it, that’s it. Maybe they’ll make you another one.

Thus the value of cultic art. The value of mass art is the value of distraction — “the distracted masses absorb the work of art into themselves. Their waves lap around it.”34 The best example given by Benjamin is architecture.35 The value of a beautiful work of architecture is not in the way a tourist feels in its presence. The value is in its use, but specifically, in the way its use contours human behavior, creates habits. You can admire a staircase as long as you want, and maybe find it beautiful, but you will never be a part of it quite so much as it is a part of you — in the way you shuffle down it every morning and up it every night, in the way you remember to drop your foot ever so slightly lower on the last step, in the way you still remember to do that decades after moving away. The “magical” or “ritual” quality becomes the most incidental aspect of your relationship to art. The art has nothing to do with you anymore. All kinds of people use the staircase. It changed them all the same way it changed you.

Mass art includes not only movies, CDs, and published books but also every work ever digitally uploaded to a public server on the Internet. Liberated from place and time, available anywhere, preserved forever, art becomes the propagation of false universals. There is little to say as an artist that is at once nontrivial, universal and transhistorical: so you lie. You lie without seeing that you’ve lied. You speak on truth and love and infinite passion, you speak that truth you found calling from every window, standing in every door: and you find that in your carelessness you have broken the hearts of people you never knew existed, taught them that the way they lived was not real, maybe today, maybe in 50 years’ time; or worse, you have become the tool of graceless anonymity, the work that fascists run to so they can hide from themselves.

“Art for arts’ sake,” art which eschews not only purpose but representation, in a cultural context that has popped out of space and time is art for nothing, the whole human race a great big O flying by the Oort Cloud — this is fascist art par excellence, as Benjamin noted:

“Fiat ars-pereat mundus,” says fascism, expecting from war, as Marinetti admits, the artistic gratification of a sense perception altered by technology. This is evidently the consummation of l’art pour l’art. Humankind, which once, in Homer, was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, has now become one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached the point where it can experience its own annihilation as a supreme aesthetic pleasure. Such is the aestheticizing of politics, as practiced by fascism. Communism replies by politicizing art.36

The value of mass art lies entirely in its purpose — what mass rituals shall it set into place?

If not art for arts’ sake — whose? Feminists’? Communists’? Of course, if you set out as an artist to politically change the face of art, you’re just making more art for arts’ sake (art as a damsel in distress and your art as the art that will rescue art from the tower) — combating false universals with more false universals. And universals never negate each other; they just pile on and on. Hence all “politicized” cultural criticism becomes a mad diving ball game where we try to decide which specificity to preserve as universal for all time — because if Frodo and Sam are “just friends,” that will obliterate all gay people forever, and if Frodo and Sam are gay, say goodbye to healthy straight male friendships!

Only art that is “a means of knowing the world” ever manages the journey back into politics.37 The more that a narrative introduces the world in all its contours — the more art reveals humans in their history, in their geography, in their sociality, in the world they build and the world built into them — the better its chance of reintroducing human beings to themselves, even across great gaps of time and culture and circumstance — the better its chance of telling a truth, a truth about a story, a truth that anyone with imagination can adapt to their own lives.

Pornography, per Carter, struggles to tell this sort of truth “because it denies, or doesn’t have time for, or can’t find room for, or, because of its underlying ideology, ignores, the social context in which sexual activity takes place, that modifies the very nature of that activity.”38 But that’s fine. There’s more than one way to cook a chicken. Porn, after all, can never be fascist art par excellence, art for arts’ sake: “it always has work to do.”39 It needs to make you cum, and in this mercenary interest it cultivates a kind of humility. How dangerous can these false universals of sensuality be if they show up in a world where cops forever are bamboozled, classes forever passed, jilted lovers forever won back with blowjobs, and parents’ divorces are forever made up for by gorgeous stepsisters!

Benjamin mused that any medium which has the power to install mass psychoses also opens up the possibility of “psychic immunity” to such psychoses: “the forced development of sadistic fantasies or masochistic delusions can prevent their natural and dangerous maturation in the masses.”40 In 2022, “transgender” hopped five places to third-most-searched category in the United States in Pornhub’s yearly insights report (Ebony remains unchallenged in first place); in 2021, the Human Rights Campaign recorded a record-high count of killings of trans people (mostly Black and Latinx trans women). These are two moments in a social process of escalating anti-trans fear and hostility: what does it mean to connect them?

Possibly this: porn is the little death and the fraud of all the false universals that hold it captive. Pornhub tails the far right in its crassness, its sexism, its racism, its homophobia, its transphobia, its furniture on loan from Country Junction, its green screen backgrounds showing all setting suns and shining towers and lightly padding waves, in its Miami without any of the ugliness that would make it Miami, in its luxury without any of the peculiarity that would betray real taste. So this is the worldly world our manly men are afraid of! The right-wing man goes about his day and preaches: God made you man and woman, before He formed you in the womb He knew you. And then he goes home and gets under his sheets and prays. His prayers: men have dicks, women have pussies, dick fucks pussy, bull cucks cuck, femboy wants daddy’s cock, girls want big black cock, men want 36-24-36. These are the harsh truths liberal politesse will never truly bridle! It seems like conservative politesse can’t handle it either — try shouting any of this at your local Lions’ Club and see what happens to you! Yet another effort, Americans, if you would become Republicans!

Of course this still doesn’t mean much until it becomes a point of intervention. Many intellectuals (including Carter on occasion) have suggested that if we tug hard enough at the erotic undercurrent of fascism we may produce its undoing: this is like saying if we clap hard enough for the jester maybe he’ll kill the king.

V. The Machine Onto Paper

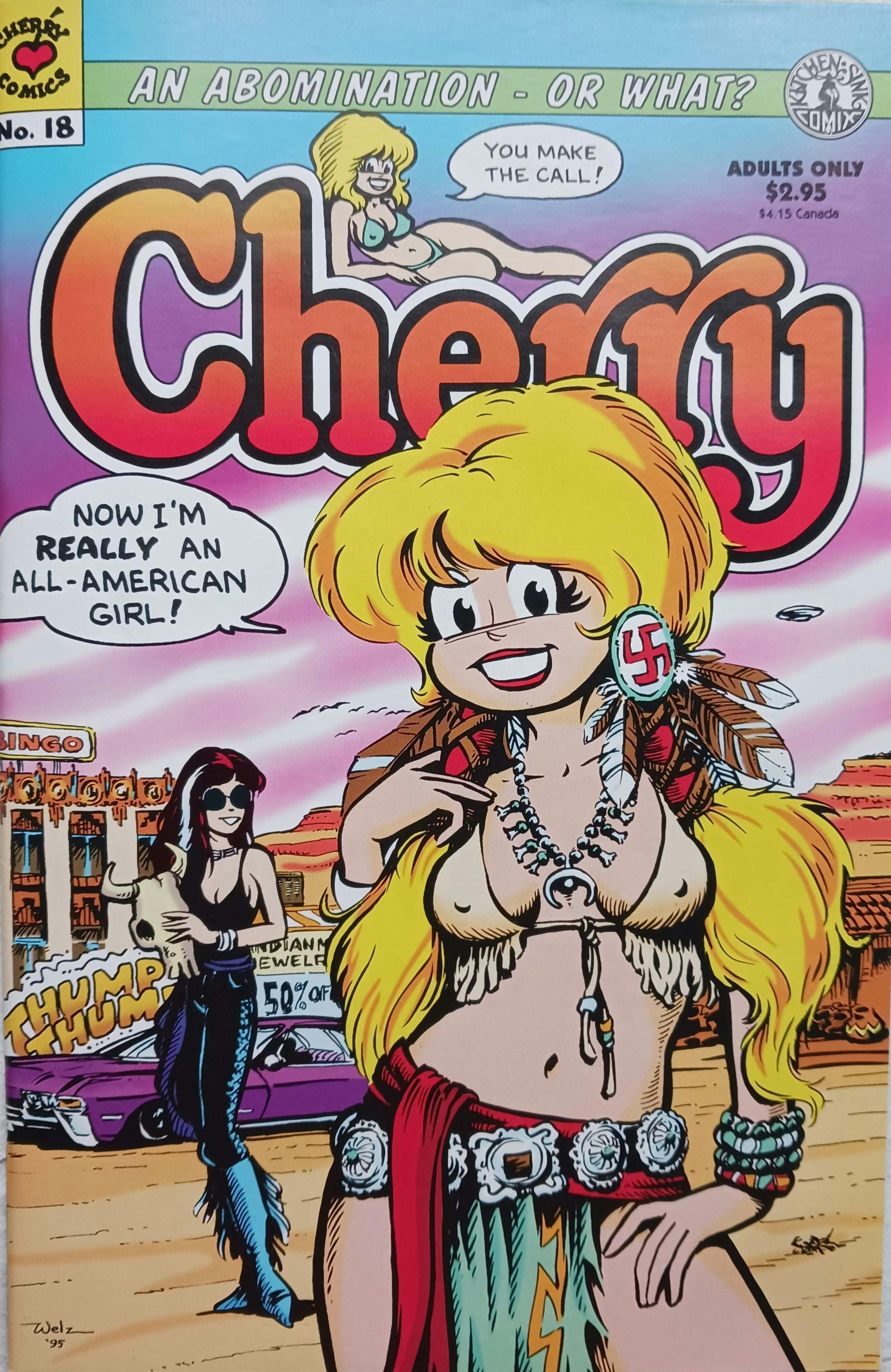

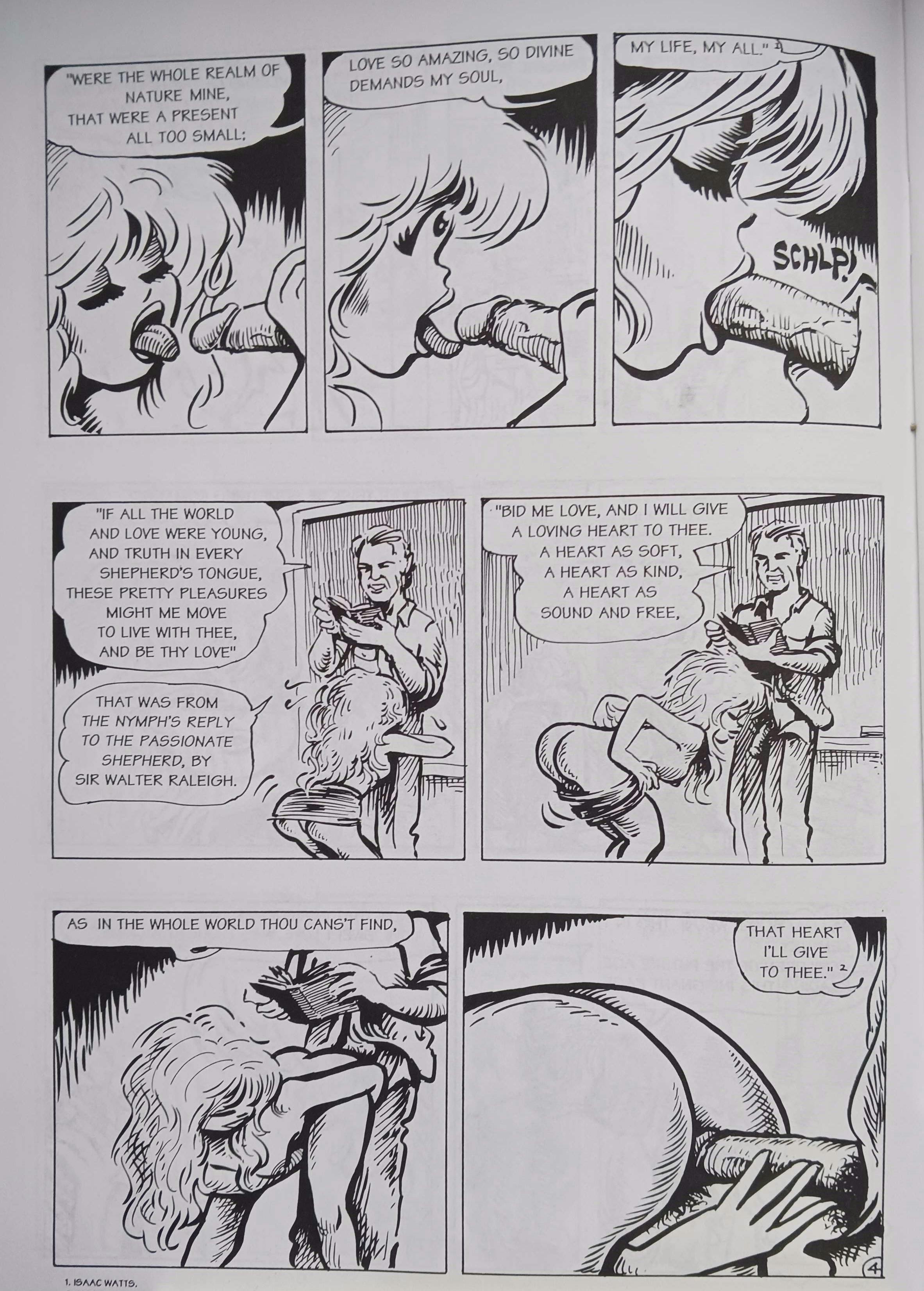

Issue #18 of Cherry, an erotic comic by Larry Welz, opens with the titular character walking to class (she has always “just turned 18”) and hearing her English teacher Mr. Le Mort drone on about Shelley and Blake. She fantasizes about him—the fantasy is rendered in loving detail:

Le Mort quotes Shelley: “The great secret of morals is love.” Cherry orgasms. The students behind her are giggling and covering their faces. She starts crying and excuses herself to see the Self-Image Counselor Ms. Renfrew. Renfrew is having a bad day and chews Cherry out for whining. Cherry sees through the prickly shell and starts massaging Ms. Renfrew’s shoulders: “It must be really hard on you to always have to be there for everyone else when you have your own troubles!” She offers a hug. Renfrew alludes to needing more than a hug and Cherry, hardly needing encouragement, offers a kiss. Renfrew’s jacket is down around her elbows. Cherry seems to be licking her neck. “Set it free!” calls Renfrew in somber ecstasy. “Release my inner…” Cherry stops her: “No! Don’t say that word! You wanna get us all in trouble?” They fuck.

Things wrap up. “Well, I dunno about you, but I sure feel better!” Renfrew agrees and notes that the pleasure was more than physical: she feels a heightened self-esteem and capacity for self-expression, which will help refresh her relationship with her husband. Suddenly she remembers: she’s meeting him for lunch. He’ll be here any minute. Cherry, all smiles, stuffs Renfrew into a shirt and pretties her up in seconds. Her husband — revealed to be Mr. Le Mort — arrives. He is taken aback by Renfrew’s “radiance” and asks what kind of morning she had. Cherry disappears with a chuckle.

Break for ads: other Cherry issues and omnibi, Cherry beach towel, Cherry door poster, Cherry T-shirt, Cherry tank top, Cherry temporary tattoos. Joke page of bizarre oral sex moves: Bob from the Church of the SubGenius is getting fucked in the nose, a woman has a toilet bowl for a mouth, a person is sitting on Alan Moore’s face. Two pages of letters to Cherry from fans. A fan named Patric declares that issue #16 “crested the Defining Horizon,” which means it was very good. A fan named J.B. asks Cherry to appear in more “real world” scenarios, as they feel more “true” than when she’s on a pirate ship or the Middle Ages, which is “imaginary.” He also asks to see less of Luccan, Cherry’s bad-boy lover from earlier strips, because it makes him jealous. Cherry replies: “Love hurts.” A woman named Jessica who owns a comic store laments that Cherry is so dim-witted and lauds the inclusion of Ellie, Cherry’s bookish brunette computer whiz best friend. Cherry takes umbrage.

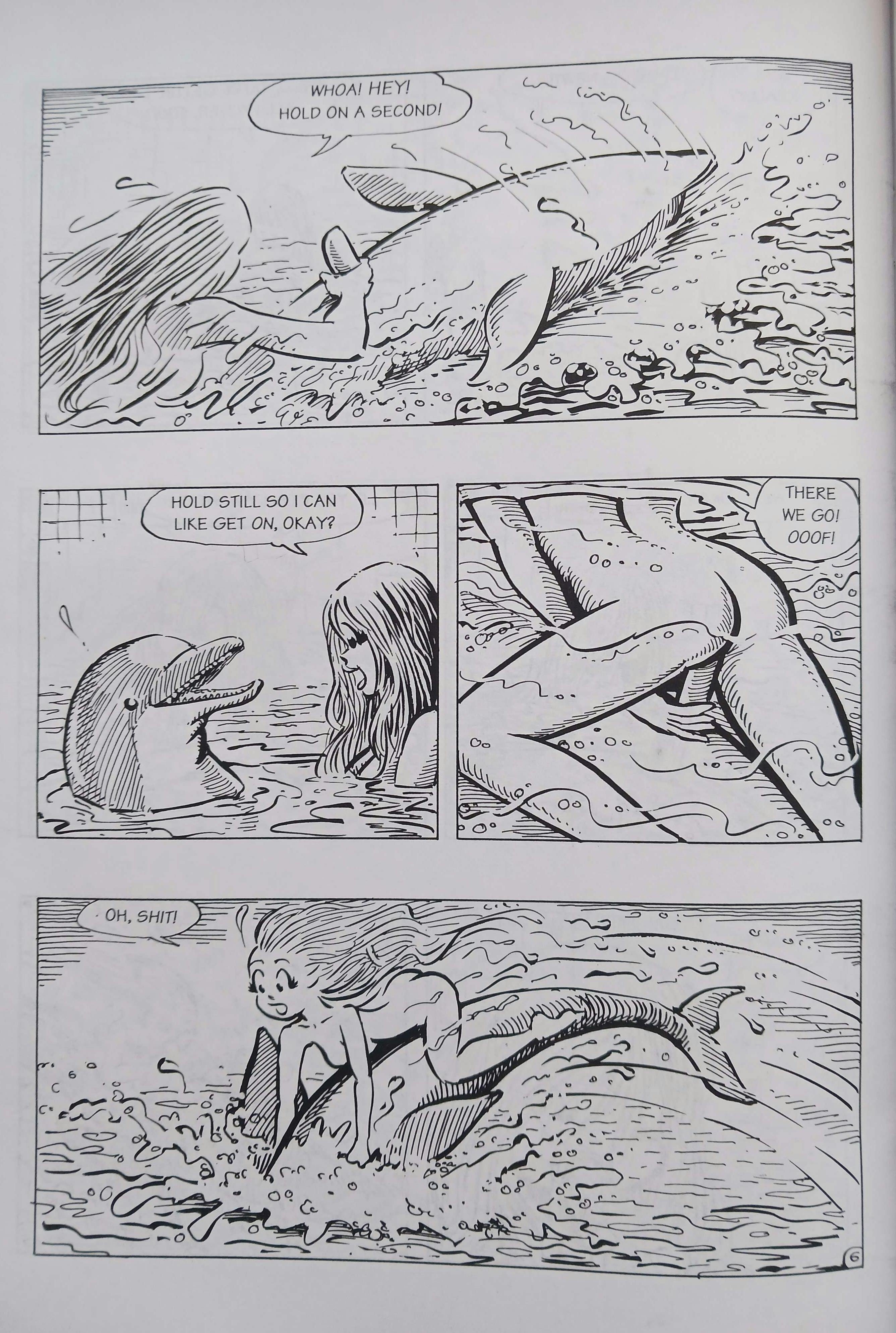

The second story is not so narratively complex, but does take better advantage of the cartoon form’s natural advantages — Cherry is fucking a dolphin at a research lab:

Cartoon porn has advantages. Cherry’s skin is without blemish. She is effortlessly svelte: her body never has to worry about holding her gastrointestinal tract or other organs. For 27 years she has never aged. She is capable of impossible acts: all over the world people are fucking animals, and sometimes they get it on camera, but never has it been so gentle, so free, and so glamorous as it is with Cherry and the dolphin. It has its disadvantages too: no-one is portrayed, no model lies tantalizingly beyond the page; one must constantly confront that one is living a lie. But Cherry, like any fictional character, is a real person: she walks and talks. Every woman knows Cherry, knows her hair, her skin, her tummy, her tits, her thighs, her legs, her head game, her joie de vivre, her sensitivity, her boldness, her softness, her 18ness: she is the bed of Procrustes onto which every one of us is stretched all the way through life. The rules of the game are more easily recorded onto paper than onto the human body.

One wishes that fantasy could leave the world already. Even if the fantasy world is made up of our world’s caricatures and so-called truths, it ought to render them alien again by taking them seriously. Good fantasy starts with a “what if?” question and then commits to it entirely, to show us something new. What if Cherry was real? What if the perfect woman was real? We are forced to imagine some hideous Pixar film where the girls coquette and squirt until the very end of the very last frame of the comic, at which point they put on a dull working-class face and go about their real day.

Certainly, Cherry makes attempts at drawing out this sort of irony. Men in her presence are generally humiliated and undone. She treats everyone with milk and honey, but it’s never milk and honey enough: fans are jealous of the cartoons that get to fuck her, and so she gets catty. There are snatches of humanity. Cherry fantasizes about her English teacher, and against her fantasies the prose of Byron seems staid and oblivious. Cherry hushes her lesbian lover, afraid of the conclusions: in saying “No!”, she draws them both into a fragile conspiracy. The way she cares for Renfrew after the sex reflects the fluid knowingness of many years of intimacy, cut-and-pasted onto a ten-minute encounter. Here the false universals seep in. Why would Renfrew dress any differently than how Cherry dresses her? All women would be better to dress that way. Cherry knows best.

No one could call Cherry a passive woman. She is always in control. But her desire is the narrative’s desire, is the reader-writer’s desire for her. She ought to fuck, so she wants to fuck. There is no conflict.

Of course, Cherry is a parody. She’s supposed to be like that. She’s a statement on the sexual absurdities of our society, or something. If she were too real, people would start thinking even more than they already do that they should be like her and that would be confusing. When she steps onto the world of letters to defend herself from the feminist comic shop owner and her Valley Girl “like, y’know” gets ten times stronger, Larry Welz is clearly the one playing defense, as if to say: “How dare you take her seriously?” Carter notes that satire, like pornography, “has an inbuilt reactionary mechanism. Its effect depends on the notion that the nature of man is invariable and cannot be modified by changes in his social institutions.”41 The premise of parody is that art can say something profound about itself, but that is impossible. When a work attacks its own stupidity, you are left with either a stupid work of art or nothing at all. Autocritique is more “art for art’s sake,” a hole in the ground.

There is a certain self-righteousness to pleasure: after all, it’s the best feeling there is. The pornographer shakes his fist and cries: “As long as there is pleasure, there will be people like us drawing pictures to carry it to new heights!” This is a truism. It invites us to imagine a future where the most erotic image in the world is the ear of a cow, where everyone is drawing exaggerated cow ears and photographing them in new and bizarre scenarios. But what would it take to create such a world? Not this lockstep obsession with the regime of pleasure as it already exists! Not this effigy basking in its intangibleness: but a human effigy, with human joys!

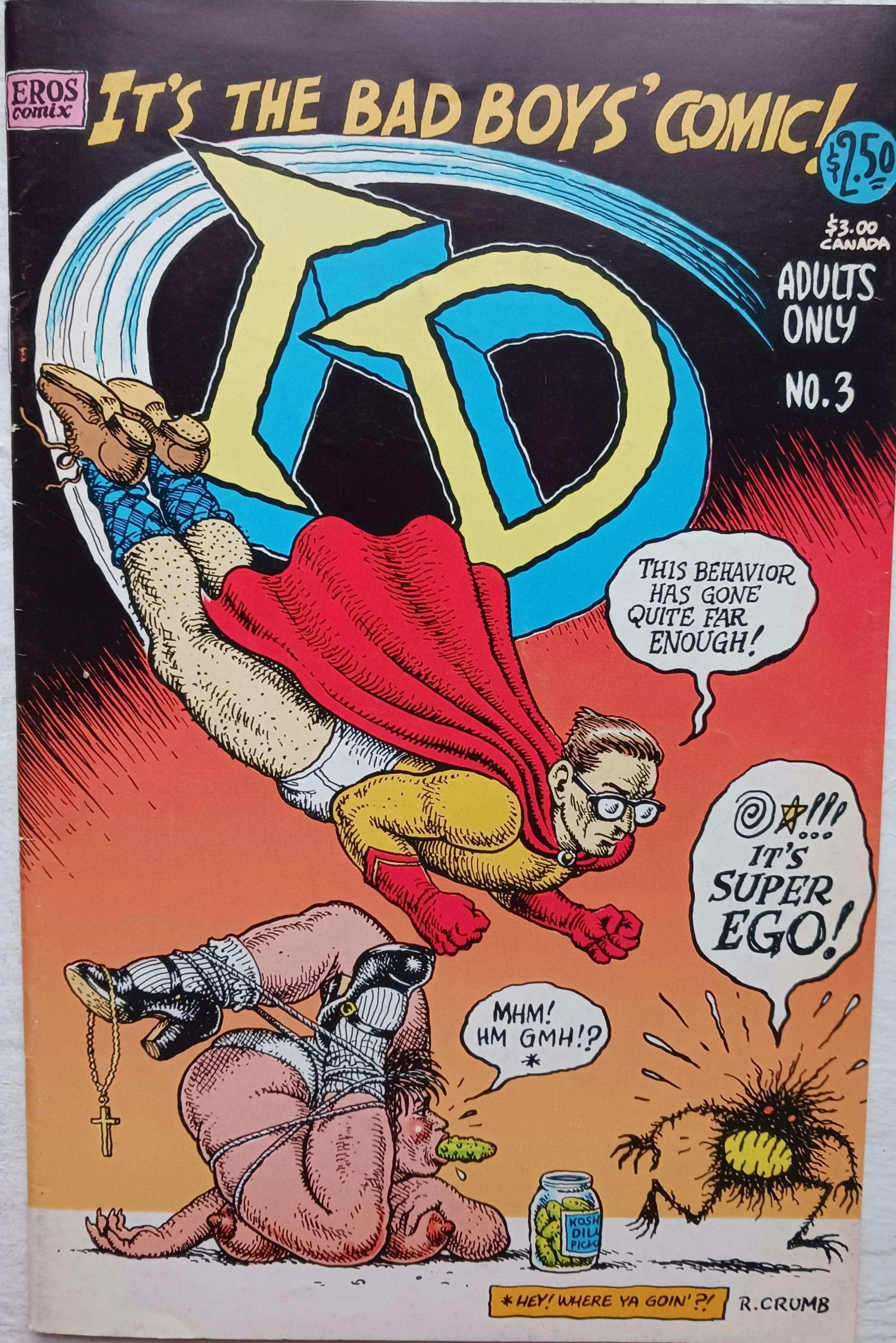

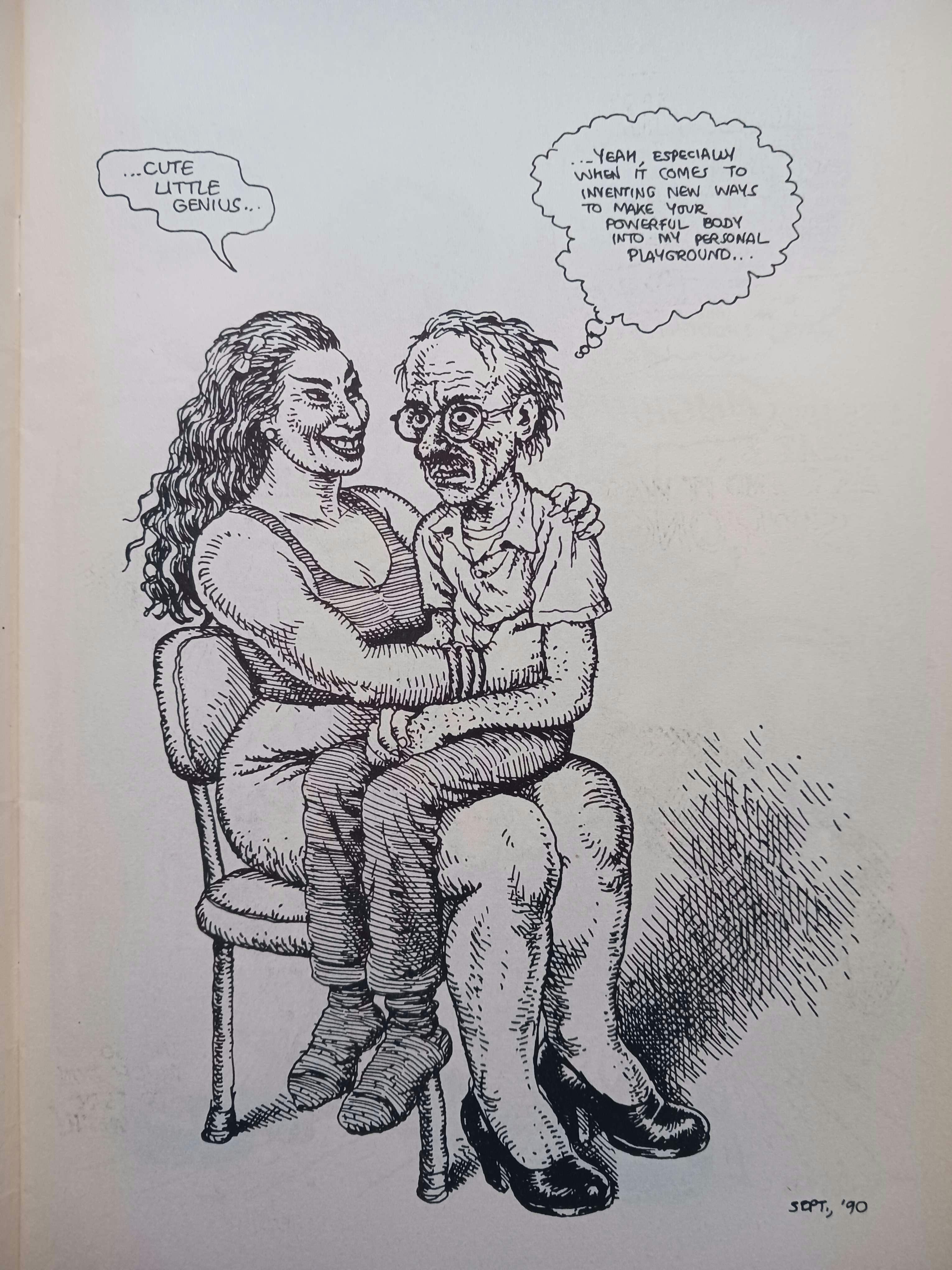

Issue #3 of R. Crumb’s Id contains mostly single-panel cartoons depicting Crumb’s fantasies (which vary, but generally include big-legged Jewish women) in various stages of realization. A woman walks by an ugly man in a supermarket parking lot; he sweats, says “Mercy me” and starts masturbating. A little girl asks an ugly little boy what he’s doing; he says “Oh, it’s you,” but his thoughts say “It is not permitted, it is not permitted…” Sometimes the woman is the only thing in the frame. She is sitting backwards in a chair, away from the artist. She is sitting on an ottoman in a tank top and gym shorts, in the pose of the Thinker. A lewd caption may accompany the picture. “Great Moments: She stood there grinning, waiting for me to do something… so I did.” Sometimes he’s actually encountering them, and there may be a touch of the erotic, but the real sex is still in his head.

Some comics are more explicit: Crumb and a woman sit on a bed, and she is leaning over to blow him through his boxers. He makes a pondering statement on the difference between fantasy and reality: “the miraculous thing is that life and art feed on each other, and there actually are moments when reality exceeds the world of fantasy to give ecstasy.” The woman: “Mmghh!”

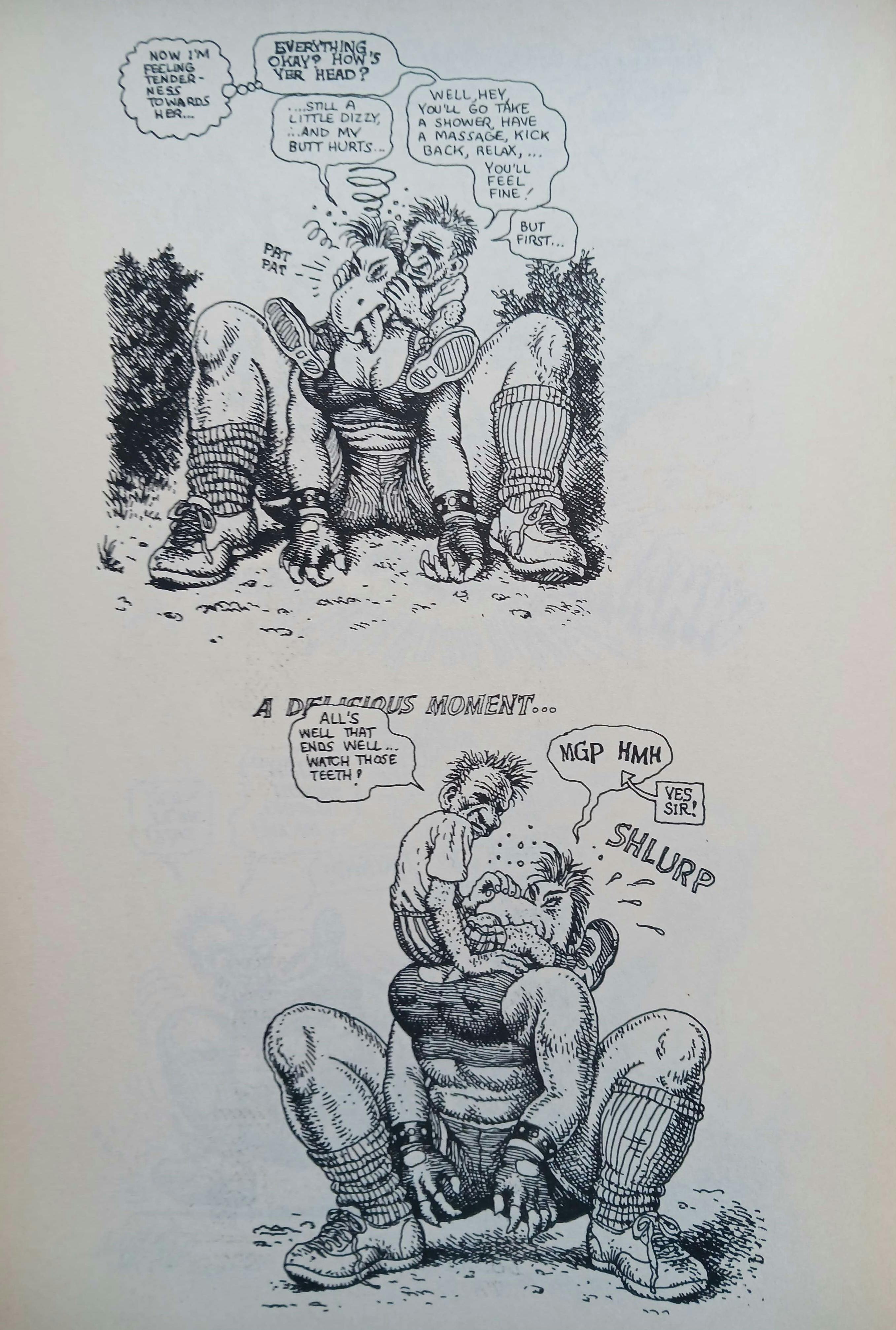

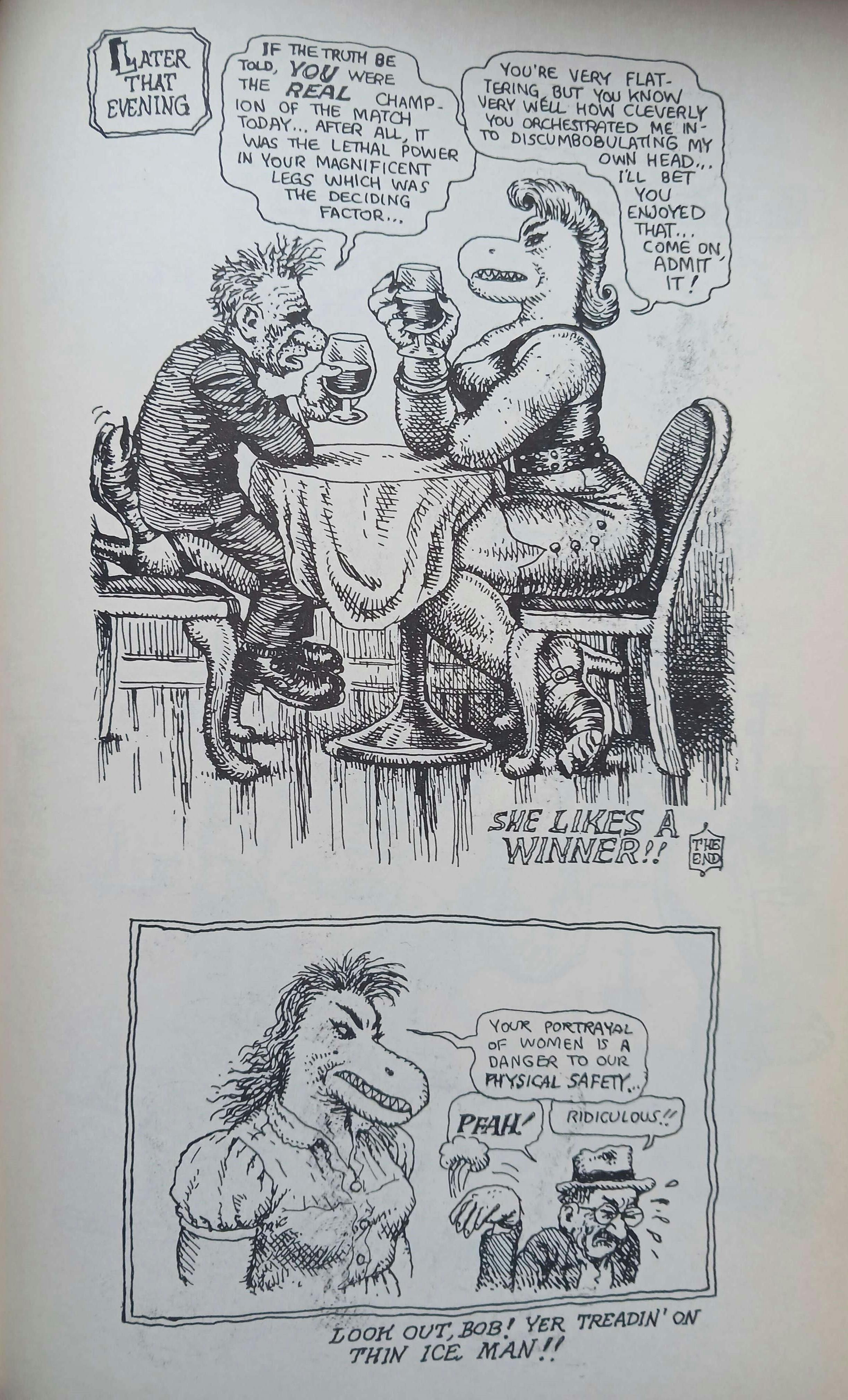

In the principle story, a tiny, rumpled R. Crumb avatar catcalls a large raptor-headed woman on the street, and she, furious, challenges him to a wrestling match and drags him off to the gym. She lifts weights and jumps 1000 ropes while he sits in the corner, his body as small as possible, hands together in his lap or curled around his torso as if he is cold. She makes him strip to his shorts and a T-shirt and carries him to the ring. He grabs her left calf and wraps himself around it. His entire body is smaller than one of her legs. After some trickery, she kicks her own head in with a massive Fa-toom! She seems dead, or out cold. She is still standing with her face all twisted around. He pushes at her ass and, with considerable effort, topples her to the ground. The referee counts to ten and announces she’s out, but Crumb refuses to clear the ring, so he opens up a flap in the boxing square (“Aww, you’re sick!”) and Crumb and his conquest drop down a chute onto the streets below. The woman’s bottom “bounces off the ground like two basketballs!” Cars are swerving and honking. She wakes up and shouts for Crumb to “do something to stop this!” “Me? What do I look like? God?” She throws her legs down and clatters to a halt. Crumb starts to feel tenderness towards her:

The strip ends with Crumb and the woman chatting over drinks at a nice restaurant.

That final panel, where a well-meaning feminist chastises Crumb for drawing the comic you just read, is a recurring gag in Id. There may be a humiliation kink at play: but even so, Crumb’s id is never so recklessly on display as his ego. He is clearly fascinated by the impact that his depiction of women may or may not have on women in the world.

Crumb’s women have this advantage over Cherry: even horse-maned, raptor-headed, and ten feet tall, they look more like real people. Their legs and arms and torsos, rather than stand in simply for legs and arms and torsos, strain and curve and betray muscles, bones, guts. Their faces have freckles, dimples, worry lines; their skin is covered in dots and journeying crosshatch textures, suggesting hair or roughness; their eyes are small, dark, grim. Most of these features stem from R. Crumb’s fetishes, but they result in a woman who is more than just simple parts.

The fact that the women are real is the start of the trouble. Dworkin notes that “women cannot enter male consciousness without violating it” unless they enter it as toys of male supremacy.42 The woman who confronts Crumb for leering at her in the supermarket, even if just with her eyes, has unbeknownst to herself enrolled in a conspiracy alongside Mommy, Daddy, Christ, the Cops, the Homeowner’s Association, the Comics Code Authority, the knitting old ladies of feminism, and every woman who has ever embarrassed him or rejected him or ignored him, not to mention his own better judgment and shame, to form an ever-scouring, repressing, excoriating fascist superconsciousness. Even the women who do like Crumb are frozen in their own moments of incompatibility; there is no impression they might share anything with him beyond what has been shared. His thought bubbles suggest that if they ever knew what was really going on in his head, they would cast him out in horror (this seems unlikely; his fantasies are fairly tame). Even when he talks aloud, he is almost always talking to himself.

A tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying — nothing. What’s up with that? Crumb is in reality no boorish virgin — he was in his second decade of marriage to legendary feminist comix artist Aline Kominsky-Crumb when he wrote this. Carter’s claim that pornography eschews showing “the social context in which sexual activity takes place” seems worth calling into question. While she is, descriptively, absolutely correct that porn does this, the social context of sex can also be pornified — and this is the project Crumb is embarking on.

A man and a woman make eye contact, approach, flirt, dance and walk home together or walk home separately in confusion — this scene is just as arousing as a blowjob and has the same chauvinist allure. Nowhere is the conflict between Man and Nature quite so stark — and nowhere the resolution quite so satisfying — as when it is between Man and Woman. Woman is the Other, but not utterly dehumanized — she occupies an ambiguity of human and animal, Man and Everything Else, a sinful little hammock slung between the friend who is easy and the life that is hard: all the damnation of space, all the poison of the woods, all the majesty of the sea, and also every ship that travels on it, and every car on the road, and somehow still another human being with a mind. So what if Truth is a woman? So what if Fortune is a woman? So what if the revolutionary will of the Masses is a woman?43

Under this state of affairs, the best woman is always the one you haven’t met. It’s no surprise that the heterosexual man has no idea what to do with himself once he’s in bed with his catch — the sex itself was never the point. Actually carrying on a relationship with a woman requires discovering that she is a human being no less ugly or mundane than yourself — a man, essentially, and that’s gay.

Much better to admire from afar! Much better in the ideology of pornography to leer, to fantasize, to read out the same tight mental heterosexual script every day of your life and never walk onstage!

“Championship Wrestling” offers the best illustration simply because the multipanel format removes all ambiguity. In the beginning the man and the woman are strangers, at the end they are fucking and dining, and in the middle there is fantasy. And what fantasy it is! Buttocks bounce like rubber, panels open in the floor, hulking goliaths can be maneuvered like sailing ships, any catcall can result in a boxing match with a crowd. Sexual conquest has been stripped of all elements of the social and turned into literal violent conquest. Crumb has, of course, found our world again by means of leaving it.

VI. A Hole Big Enough for a Person

Anyone who’s ever worked a shitty servile repetitive job at McDonald’s or Target or Amazon, for $9 an hour, for abusive bosses with wretched schedules destroying their social life and destroying their body, knows the familiar cope — I like it here, I like the work, I like knowing how to do it, I like doing things I’m good at. This makes sense. There’s nothing inherently demeaning about making sandwiches or folding boxes or putting items in a bag — work, the channeling of human power, is perfectly enjoyable, exhilarating even, once you’re in the rhythm. If only they weren’t such assholes! If only they paid us better, if only they didn’t turn pointless sadism out of every interaction, if only they gave us chairs, if only they gave us time to piss, then I’d be so much happier and I’d be a better worker because I’d be happier.

But of course your happiness at work is just the minimum happiness required to preserve your life. It is a fact that if you did not do this dull, pointless, demeaning, body-destroying, life-ruining labor for most of the day most days of the week then you would run out of money and starve on the street. But if this is the only way you can think of it, every hour on the clock, you aren’t going to last very long. So you think of other reasons. You have pride in your work. You like knowing what you know. You like the dumb stories and drama. You like your coworkers. You like the pace. You like having something to do. You like folding shirts: it’s certainly better than being up at the register. Escape paths come and go (an offer from an uncle, an opening at another store with better pay) and you ignore them because, hey, you like the work. It really fits you.

This is the Sadeian ultimatum delivered via Dworkin: you can’t choose not to get fucked, but you can at least choose whether or not it’s rape: lie back and enjoy yourself or scream and suffer: that’s the only freedom you have in this life: a freedom of attitude.44

It’s not enough to demand freedom to do what we want when our wants are being hollowed out and filled with the wants of others, when in order to survive we’ve had to learn to desire the worst for ourselves. Rather we must always ask: Whose wants are mine? The answer is rarely a specific person but a force that acts out in different degrees through everybody. Of course in the typical, individual case, there’s no shame in wanting what was wanted for you since long ago: unless your life has become a point of intervention and a vector for collective struggle, you will always play a role, a role handed down out of history, a role ready-made for ideology. The ideology of pornography is refreshed in gulps from the ascetic and the libertine alike.

“Woman’s love,” says Beauvoir, “is one of the forms of expression in which a consciousness makes itself an object for a being that transcends it.”45 She compares it to the cloistered girl’s love for Christ, but in Dworkin it is the love of Christ, of woman-as-Christ, “Christ of cunt and breast, Eve’s fallen, lustful, carnal descendant, the victim who, unlike Jesus, is suffering for her own sins.”46

Man does not escape this hollowing-out and filling-up simply through his transcendence, for transcendence will always be squandered in his hands and he knows it. He becomes Sade-Christ, Sade who “died for you — for all the sexual crimes you have committed, for all the sexual crimes you want to commit, for every sexual crime you can imagine committing.”47 Crumb lampoons himself with his own pen because he can feel the eyes of History on him and it drives him insane.

Every story is a Christ-story and every Christ is full of holes. The holes that make Christ suffer are also the holes through which we see ourselves and the holes through which we enter Him and climb around in Him. It is not enough to analyze character in terms of agency. The question of agency is a ruse because the final questions asked by art and literature are always the questions of the world that puts it up in the gallery, and they are questions too deranged for sunlight. “The central question is not: what is force and what is freedom? That is a good question, but in the realm of human cruelty — the realm of history — it is utterly abstract. The central question is: why is force never acknowledged as such when used against the racially or sexually despised?”48 When analyzing characters who are racially or sexually despised, we must always ask “Who put the holes in them and why? Who can enter them and walk around in them, and where do they get?”

The hole left in Cherry is a hole made for the reader’s cock. Her mind is revealed only by way of her sexuality. She announces what she wants and how she feels in quips and asides, and there’s no need to wonder about any deeper internality; she’s not going to surprise you. As for how it really feels to fuck Cherry, well, now you’re left to your imagination.

The hole left in Suko is not too different — but Suko is more clearly a conscious attempt to know the world, complicating the situation. Smudges of characterization aside, people very similar to Suko do exist and, if art wishes to know the world, it must know Suko. How do you do this when readers are so ready to enter Suko and walk around in him in a violating way? This points to problems that art and critique cannot solve.

The hole left in Justin, flatly unrelatable and locked up in himself, is the hole left also in Sade’s libertines — a hole “large enough for a flaying, a castration” — large enough for a person.49 He can feel pleasure only by violently denying his partner the chance to know the same — “and so the self knows it exists.”50 He has occupied a sexuality that cannot be shared, because to share is human but Justin knows he must be anything but — he is a monster, a Christ — a child locked in a cupboard: “the triumph of the will recreates, as its Utopia, the world of early childhood, and that is a world of nightmare, impotence and fear, where the child fantasizes, out of its own powerlessness, an absolute supremacy.”51

It is no surprise that Carter (and Beauvoir, and more than enough men) read Sade and said “I could fix him.” In all 1200 pages of Juliette, there is not one moment of tenderness: it seems if you can reach through the “fringed hole” of Sade’s sexuality and behold yourself, then you can behold yourself anywhere.

The 20th century experiment of rehabilitating Sade has failed. Its results are recorded. But there are always new holes to be made and the project of making new holes in old Christs is always a worthwhile one. This is the mode Carter operates in — and it’s the dominant mode of counterculture art reception in the Internet era. Against the teenage boy beating off to Jodie Foster, we place the teenage girl who watches American Psycho and declares that Christian Bale is an egg52, a repressed gay man, or simply a loving and fragile soul who unravels because he falls short of the psychopathy that corporate masculinity demands.53 Interpretation can never salvage art, but it is art, which is why this school of interpretation quickly becomes a school of fiction — even the crudest slutty Marvel fanfic smashing action figures together quickly piles up more pores of human feeling than its source material.

In Centurians of Rome, the main plot is the love story between Demetrius, sold into slavery, and Octavian, racing after and desperately trying to set him free. Octavian submits for some time to the ravages of the slave-driving commander, who is hopelessly obsessed with him, and learns to be kind to the commander’s doomed love. Ultimately, the commander frees Demetrius and lets the two run off together; he loves Octavian enough to set him free to a happier life. The Emperor, incensed, punishes the commander by making him replace Demetrius as his sex slave. Are these holes large enough for a human to fit in? In broad strokes, yes. What can be done to carry it further? Largely, it’s a matter of good old-fashioned better craftsmanship; the dialogue in Centurians is so bare and confused, and the final film quality so poor, that this storyline is just papering for a series of sex scenes. Characters are not realized with any veracity, and so sex is not, in the end, real sex.

It is also a matter of creating art without a call-boy pimp at the controls — but this points, again, to the work that critique cannot do.

VII. Points of Intervention

Creating liberatory art is no riddle. If you want to transform an institution, you organize the workers—the people who through their labor reproduce that institution. If you want to transform an image, you organize the people who through their labor reproduce that image.

The White Man “designs” the sexualized and racialized image to fit his fancy, but he uses sexualized and racialized people as his instrument and without that instrument, he is helpless.

So far in my analysis of the ideology of pornography, I have been frank when discussing its political economy, but generally kept it on second fiddle. When planning political action, this distinction becomes impossible.

If you want to transform the pornographic image, then you should be focused on organizing sex workers, who reproduce pornography as its primary workforce and subject matter. In no person are so many sexualized and racialized images so likely to be convergent as in the sex worker. This organizing is especially important because sex work is a less mystified form of oppression than work under capitalism overall: it throws you to the fringe of society, against the family, the politicians and the police, and into conditions transparently brutal and arbitrary. A certain amount of collusion and class war is necessary just to keep workers safe. Capital compels its own resistance. The situation is similar in prisons and amongst the hyper-exploited proletariat of the Global South.

To “intervene” in this class war is not to import revolutionary theory from the outside like some door-to-door Bible salesman. To understand organizing as something that Communists do to workers is to flatten the contradiction between workers and Communists into the contradiction between the wretchedness of the world and the cleverness of the individual, which is never going to get you far.54 Instead, you must investigate each situation, help where your help is most warranted, and build trust through forging common projects. Once people have a common project, the mist falls away and they become graspably on the same side, and an opportunity arrives for a real play of contradictions without dogmatic oppositions.

For gestative organizing efforts with names, we can point to something like the Sex Workers Outreach Project. Nationally it has a clear focus on political advocacy, but specific chapters have found ingenious ways to reduce the harm that boyfriends, pimps, and johns are capable of (it’d be a massive overstatement to say it can stop them) through networks of mutual aid and interpersonal assistance. The Sex Workers Against Work manifesto (passed on from a “clandestine whores’ network”) pushes this ideological line:

We do not believe our liberation will be reached through a permanent position within capital, to then be exploited in more efficient ways…. Work is not something that confines us solely as we labor in a building or room. Work orders the rest of our life: our mornings, our vacations, our purchases, what we read, our care, our sex and pleasure, our home, the night. The more legitimized our labor becomes by the state and capital, the more we are forced to work. We want an end to criminalization, an end to work, and also an end to capitalism altogether.

Decriminalization is the line of struggle for all these organizations and so to join the class struggle is to push for decriminalization. Any other position is liberal obstinacy. At the same time, decriminalization is not enough, and if not embedded in a larger movement to abolish the present state of things, it will become a line of assimilation into new forms of oppression. Sex workers’ struggle against naked oppression is the struggle against the police and against the prison: it is not a plea for new legibility within state lines, but a struggle for power whose real horizon is revolution.

Notes

- Andrea Dworkin, Pornography: Men Possessing Women (Toronto: Penguin Press, 1989), p. 57.

- “In authentic possession, the other as such is abolished, it is consumed and destroyed.” Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, transl. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (New York: Vintage Books, 2011), p. 181.

- Poppy Z. Brite, Are You Loathsome Tonight? (Springfield, PA: Gauntlet Publications, 2000), p. 83.

- Ibid, p. 93.

- Beauvoir.

- Brite, p. 86.

- Angela Carter, The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), p. 14.

- Carter, p. 17.

- Andrea Dworkin, Woman Hating (New York: Penguin, 1974), p. 75.

- Many theorists prefer the term “social reproduction” for this reason (and other reasons), though it does not escape the bind entirely.

- Beauvoir, p. 73.

- Karl Marx, Political and Economic Manuscripts of 1844, ed. Dirk J. Struik, transl. Martin Milligan (New York: International Publishers, 1964), p. 72.

- Ibid, p. 113.

- Beauvoir, p. 267.

- Sadie Plant, Zeros and Ones, p. 18.

- “The emancipation of woman will only be possible when woman can take part in production on a large, social scale, and domestic work no longer claims anything but an insignificant amount of her time.” Friedrich Engels, Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, trans. Alick West, p. 88; accessed here.

- Beauvoir, p. 147.

- Carter, p. 78.

- W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America (New York: The Free Press, 1935), p. 62.

- Du Bois, p. 12.

- Ibid, p. 15.

- Ibid, p. 14.

- Carter, p. 27.

- I took the concept of abstract machines from Deleuze and Guattari, particularly the “Year Zero: Faciality” chapter of A Thousand Plateaus: “the abstract machine… produces faces according to the changeable combinations of its cogwheels. Do not expect the abstract machine to resemble what it produces, or will produce.” Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), p. 168.

- Konstantin Stanislavsky was a noted Russian and Soviet thespian who believed that actors should meld effortlessly into characters and that the audience should be swept along in a play. Bertholdt Brecht was a noted German Marxist thespian who believed that actors should maintain a distance from their characters and that the audience should understand clearly that a play is just a play. Wu Zuguang, Huang Zuolin, and Mei Shaowu, Peking Opera and Mei Lanfang (1981, New World Press), p. 26.

- Ibid.

- Carter, p. 13.

- Fred Gormley, “My Brief Career in Porn,” Christopher Street issue 84 (1984), p. 43.

- Ibid, p. 41.

- Ibid, pp. 42-43.

- “Paid Notice: Deaths GORMLEY, FRED C., JR.” The New York Times (Nov. 25, 2002), section B, p. 9.

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version,” 1936, The Work of Art in the Age of its Mechanical Reproducibility, and other Writings on Media, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Harry Zohn, ed. Matthew W. Jennings et al (Cambridge: Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), p. 26.

- Ibid, p. 40.

- Ibid.

- Buildings are not mechanically reproducible like movies or photos, but, because they are large and last a very long time, they are mass art in Benjamin’s sense—they affect great masses of people.

- “Fiat ars-pereat mundus” = “Let art flourish—and the world pass away.” Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was Italian Futurist and Fascist poet whose poetical defense of the genocidal colonial occupation of Ethiopia is cited earlier in Benjamin’s essay. "L’art pour l’art“ = "Art for arts’ sake." Benjamin, p. 42.

- Carter, p. 13.

- Ibid, p. 16.

- Ibid, p. 12.

- Benjamin, p. 38.

- Carter, p. 16.

- Pornography, p. 64.

- It’s been quipped that sectarian differences among communists burn hotter than hatred for the cops because the Enemy is just an enemy, but those seeking to out-organize you are in love with the same woman. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to trace the origin of this quote.

- Ibid, p. 94.

- Beauvoir, p. 305.

- Woman Hating (New York: Penguin, 1974), p. 72.

- Pornography, p. 89.

- Ibid, p. 146.

- Carter, p. 36.

- Ibid, p. 142.

- Ibid, p. 148.

- Slang term for a trans woman who doesn’t know it yet.

- As one example, I’m thinking of the very good review by Nathaxnne (accessed here): “Patrick’s problem is that he is insufficiently a psychopath, that his conscience eats at him, that he would rather be listening to music and making art and maybe writing a food column for the Times, that he feels bad about killing or wanting to kill in a world that runs on killing, that really doesn’t care.”

- It can also go the other way (i.e., the ingenious self-reliance of the Oppressed People against the wretched ignorance of the Academic), which is obviously not any better.