A Constellation of Reactions to History

Part 2 of 6

April 2021

Table of Contents

Fidelity

- Ethics of Transcendence

- Self-Destruction and Rebirth

- The Human Body

Good Faith

“There exists no stronger a transcendental consequence than that of making something appear in a world which had not existed in it previously.”

— Alain Badiou, Logics of Worlds, 2006

“Late at night sometimes it helps

If you don’t have to be all by yourself

In a moment life could end

And this could all be over with

I know you’re in here somewhere

You came out alone

Something you need

It’s been so long

Gotta find the one

Who’ll hold you tight.”

— Frank Ocean, Endless, 2016

There are only two tenable ethical systems. The first one completely denies the truth-value of ethics, relegating all ethical claims to the sphere of opinion. The second one assigns ethical status to transcendence.

The difference between the two systems begins with a fundamental question: is it “better” to exceed matter than to remain at the default level of Being? If you deny that universal validity could be attributed to the assertion that there is something “good” to be found in the two objective modes of transcendence over matter — life and subjectivity — then you can safely respond that there are no differences in value between matter, life, and subjectivity, and that the ethical claims I am about to make are no more valid than those of anyone else. But if you believe that living things and subjects have unique access to anything that can be truthfully described as “good,” then you must affirm life and subjectivity as the only universally-valid foundations for ethics.

Life is what elevates a lump of matter beyond its existence as an arrangement of particles. Living beings practice self-preservation and ceaseless change in a manner that distinguishes them from their constitutive elements: they methodically import and export matter and energy, alter themselves and their surroundings to suit their interests, and perpetuate themselves in new configurations. It is this activity in excess of the laws of physics, this deviation from material monotony, that allows The Good to be born in its primordial forms: creativity and generation, endurance and consistency, transformation and novelty, dynamism and discontinuity. To say that these tendencies of life are truly good is to say that it is truly better for there to be something more than for there to be nothing other.

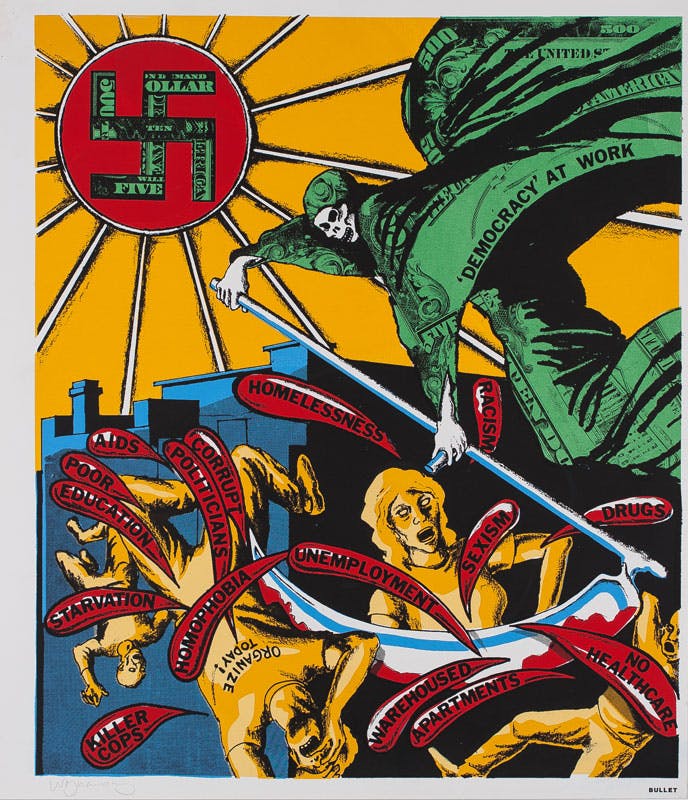

Every living thing eventually loses possession of life and reverts to mere matter, but I claim that it can still be truthfully asserted that it is “better” for the return to dust to be delayed. Ignore the silly panpsychist fetishism of the Speculative Realists and New Materialists — to become a lifeless object is to lose everything worth having. Only if life truly matters can the existence of a “surplus” population and avoidable instances of the mass destruction of life such as climate change, imperial conquest, and the uncontrolled spread of coronavirus be described as “unethical,” outside of the register of fickle personal opinion and contingent social consensus. This valorization of life contradicts the moral code of the capitalist system of social relations, which is always forced to rationalize the death it creates, the starvation, treatable illnesses, State violence, and other sources of life-destruction that bourgeois morality must allow itself.

Pleasure, which was introduced when animals attained consciousness, is certainly not the Highest Good, or even particularly high up, but it is indeed one of life’s good attributes. Although pleasure, as an animal trait, is not a source of ethical action, the unnecessary deprivation of pleasure, just like the unnecessary deprivation of any other good thing, is unethical. Capitalism does encourage the proletariat to pursue certain types of pleasure —the pleasures most useful for the purposes of profit-making and political docility — but in order to reproduce itself this unnecessary social form must deny the people who comprise the proletariat other pleasures: the pleasure of spending free time with loved ones, the pleasure of abundance, of manysided life, of genuine novelty and experimentation.

So where does ethics come from, if not from pleasure, or from the emptiest of signifiers, “happiness”? Ethics enters into Being as the Truth of the Becoming of the subject. In Logics of Worlds, Alain Badiou put forward the following formula: “There are only bodies and languages, except that there are truths”. In Badiou’s system, a transcendent Truth induces a subject, and each individual has an ethical obligation not to “give ground” relative to the Truth that birthed their subjectivity. With all due respect to Badiou, I would like to propose a modification of his order of operations. In social reality, there are only bodies and languages, except that there are subjects. The transcendent subject-in-development is forced to carry the weight of a foundational ethical truth, which can be formulated as the obligation not to give ground relative to subjectivity. There is nothing inherently ethical about Truth; it is ethical to be truthful only with regard to the truths of subjectivity.

But what is the relationship between the subject and the human being? In other words, what of the “Mind-Body Problem”? There is no problem. It is true that subjectivity cannot be reduced to life, that its contingent advent introduced something truly new into the universe, but there is no clean split between Body and Soul, between Nature and Homo sapiens. When the signifier rudely tugs the featherless biped’s head out of the soil, this special animal does not escape the earth, and there is still some dirt in its hair. Hegel, that notorious Idealist, taught that “Spirit” can only participate in Being through physical, life-sustaining things like “bones” and “brain fibers,” and yet Spirit is not only a bone, it remains “something more and other than these bones”. Rimbaud’s hellmate was right to exclaim “I wasn’t born simply to become bones!”. There is no subject without objects, there is no subjectivity without bodies and languages, without life, yet the subject is not only its constitutive objects, subjectivity is not only the effect of the central nervous system and the alienating signifier, is not only an attribute of life. Life participates in Being through matter, and the subject participates in Being through both life and matter, but the three levels of existence do not coincide. We are in, of, and beyond our worlds.

The subject is not “transcendent” in the sense of an unthinkable Absolute Other, something that comes from nowhere and cannot be deduced or experienced. The link between the brain and subjectivity is not mystical or unknowable. Through her engagement with advances in neuroscience, Catherine Malabou has elaborated and further theorized the nature of the reciprocal, “plastic” connection between the “brain fibers” and the strange remainder that they anchor. Subjectivity is “transcendent” in the vernacular sense: ascending above its origins, immediately distinguishable from everything regular, impossible to contain within the usual limits, forcing a total reassessment of that which came before it. A radical exception to the ordinary. The infinite value of this exception is the reason Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata declared “I would rather die on my feet than live on my knees!” — and who knows how many Zapatas there have been, how many people throughout time have willingly let go of their claim on life for the sake of subjectivity?

The logic of that sacrifice is the logic of Jacques Lacan’s famous conclusion to Seminar VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis (1959-1960): “the only thing you can be guilty of is giving ground relative to your desire”. Lacan’s teenage rebellion against his petit-bourgeois family’s devout Catholicism was encouraged by the life and thought of Baruch Spinoza, whose courageous rebellion against the stifling orthodoxy of the leaders of Amsterdam’s Jewish community earned him an assassination attempt and a writ of excommunication. Lacan’s Ethics of Desire stems from Proposition 57 in Book 3 of Spinoza’s Ethics (1677), which equates the discordance between the different desires of different individuals with the discordance between the essences of different individuals; from Spinoza, Lacan learned that you are what you desire, which means that betraying your desire in response to a command from your reactionary Catholic grandfather or from the dogmatic elders of your synagogue is tantamount to ceasing to exist as a subject. Traitors die a thousand times before their deaths. In Samurai Rebellion (1967) — directed by Masaki Kobayashi, cinema’s greatest advocate for rebellious subjectivity — Ichi, Yogoro, and Isaburo decide to disobey their rulers, defy their relatives, and sacrifice their own lives rather than succumb to the overwhelming social and political pressure to turn their backs on love; before fighting a battle he knows he will lose, Isaburo joyfully shouts: “For the first time in my life, I feel alive!”

To give ground relative to your desire is to “return to the common path,” to be sent back to what Lacan called the “morality of power, the service of goods,” goods as defined by your ruling class (satisfaction, wealth, stability, productivity). In Leon Trotsky’s definitive essay on the Ethics of Bolshevism, “Their Morals and Ours” (1938), he wrote that “morality is one of the ideological functions in the class struggle,” as “the chief function of official morality” is to help “the ruling class force its ends upon society” by defining its interests as “good” and construing any ideas, organizations, or mass movements that threaten its interests as “evil”. Thomas Hobbes said that “authority, not truth, produces law,” and his aphorism does not only apply to written laws — the Sovereign Good is the good of the sovereign. Michel Foucault, the great scholar of the genealogy of ethics, has much to teach us about the roles played throughout history by relations of power in the constitution of the subject-as-ethical. In Lacan’s Ethics of Desire, it is imperative to protect your subjectivity from these impositions by questioning the truth of the moral laws propagated by those who try to control you, by rejecting the desires prescribed by your ruling class. The contrast between subordinating yourself to the service of official goods and standing firm with regard to your own principles is the contrast between living on your knees and being willing to die upholding your values, the sacrifice that immortalized Antigone.

Self-determination is possible because interpellation into ruling class morality does not go off without a hitch — during the process of social subjectivation, something escapes. The powerful operator tries and fails to totalize because the One is not; State knowledge can never fully absorb and obscure disruptive Truth. There is always something of the Real that the producers of official meaning cannot account for. Lacanian theorist Joan Copjec faulted Foucault for failing to perceive this “surplus existence that cannot be caught up in the positivity of the social”.1 If subjectivity is the surplus over life conditioned by the autonomy of the signifier, then ethical subjectivity, which can only be actively-exercised subjectivity, is the surplus over State-sanctioned consciousness conditioned by the cracks in the foundation of a given Symbolic Order, the Real pressure points between a social form’s tectonic plates.

Ethics exists insofar as the “Big Other” does not. We could not act ethically if there were no limits to the power of the moral authorities of our societies. Yet this lack of the Other is equal parts liberating and horrifying, because it denies us the comfort of an Other capable of relieving us of ethical responsibility by serving as a guarantee for the ethical validity of our actions. The essential relation between the absence of an Absolute arbiter, the possibility of active subjectivity, and the difficulty of ethical action is a core principle of Jewish Ethics. As Aharon Lichtenstein explained, there are innumerable questions regarding right conduct which Jewish religious law (Halakha) is not equipped to answer, and this limit is the source of the requirement imposed on autonomous Jewish subjects to find ethical “complements” or “supplements” to Halakha, a process the Talmud describes as going “beyond the line of the law [lifnim mishurat hadin]”. Walter Benjamin singled out the contradiction between “Thou shalt not kill” and the Jewish license to kill in self-defense as an emblem of this power/burden: God’s Commandment “exists not as a criterion of judgment, but as a guideline for the actions of persons or communities who have to wrestle with it in solitude and, in exceptional cases, to take on themselves the responsibility of ignoring it”.2

In one of the most well-known fables of the Talmud — set in the aftermath of the failed Jewish rebellion against the Roman occupation and the Roman destruction of the Second Temple, a time when Jewish religious authority shifted from aristocratic dynasties of priests to community leaders and teachers — the high council of Jewish sages deliberates on the kosher status of the “oven of serpents”. Rabbi Eliezer ben Hurcanus argues forcefully in favor of the oven’s purity, but the majority rules against him. Eliezer calls on God to intercede on his behalf, and He does, three times: He sends a carob tree flying, He causes the water in a stream to turn backward and flow in the opposite direction, and He caves in the walls of the rabbis’ study hall. The rabbis are not impressed. The Talmud says that as the walls are collapsing, Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah “scolds” them: “If Torah scholars are contending with each other in matters of Jewish law, what is the nature of your involvement in this dispute?” The walls stop falling. A divine voice then calls down from Heaven to support Eliezer’s position. Joshua stands up and quotes the Book of Deuteronomy: “The Torah is not in Heaven”. The oven is ruled impure. Years later, a member of the high council encounters the prophet Elijah and asks him how God reacted to Joshua’s bold disobedience. Elijah replies that God smiled and said: “My children have triumphed over Me; My children have triumphed over Me”. Joshua’s fearless avowal of his access to Truth in the face of literally-miraculous counter-evidence should be read as the ultimate endorsement of subjectivity’s status as the portal to infinity. Subjectivity is Jacob’s ladder (my Bar Mitzvah Torah portion), binding Heaven and Earth together.

The existence of this link is what enabled a regular guy like Enoch to become Metatron, King of the Angels, Celestial Prince of the World, Guard of the Divine Throne.

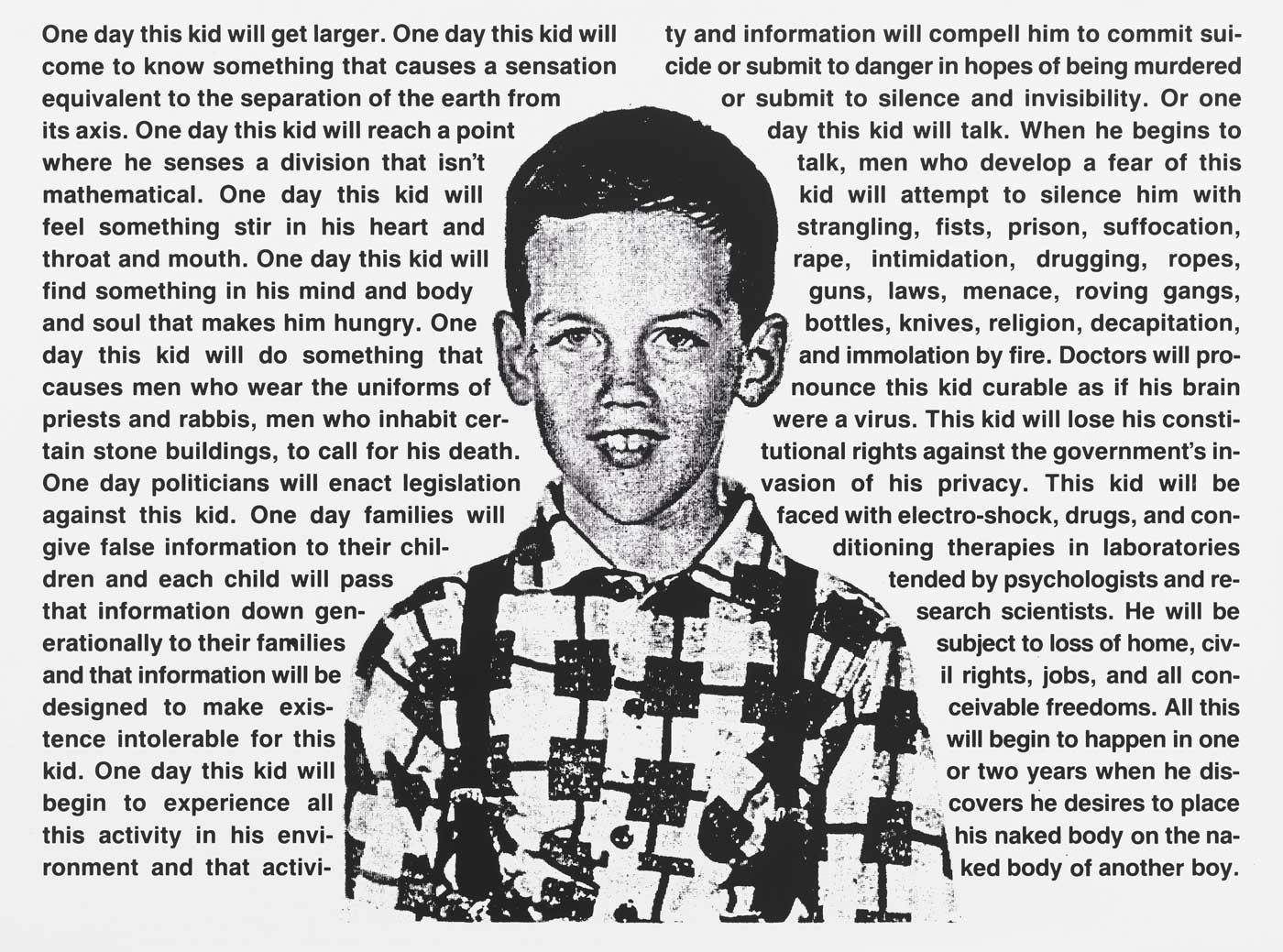

It is therefore not enough to preserve static Being-in-the-World; unlimited space must be allotted for dynamic ascension into the celestial. The word “dehumanization” signifies the reduction of human-as-living-thing to human-as-number, human-as-machine, or human-as-parasite, but it also signifies the reduction of human-as-subject to human-as-animal, or human-as-infinite to human-as-finite. The contemporary declaration of the ethical imperative to protect threatened “bodies” and center marginalized “voices” is correct but incomplete, because it does not properly emphasize people in their capacity as thinking, deciding, acting subjects. When Frantz Fanon was encouraged to “get used to” racial oppression, to adjust to his social status of “Nothingness,” of being nothing more than “a toy in the hands of the white man,” he wrote: “I refuse to accept this amputation. I feel my soul as vast as the world, truly a soul as deep as the deepest of rivers; my chest has the power to expand to infinity”.3 The highest ethical violation is the violent denial of access to infinity, the forcible suppression of the expansion of subjectivity, and throughout history, in every single context, every single system of social relations, this violation has provoked the same reaction: rebellion.

/

/

/

What makes the desire of the rebel any more legitimate than the desire of the reactionary; why is it “right” to rebel against reactionaries? Plenty of fascists have been loyal to their beliefs to the bitter end — does that mean the unwavering combatants on both sides of the class struggle are equally ethical, or that you could flip a coin to pick a side as long as you stick to your commitment (Chigurhian Ethics)? Is there no ethical distinction to be made between an anti-colonial rebel and a colonial soldier if they are both true believers in their respective Causes? “Say what you want about the tenets of National Socialism, Dude, but at least it’s an ethos.” Lacan denied offhand that his ethics offered the “moral cleansing” or “disturbing alibi” of a do-whatever-you-want mentality, but what basis is there to deny that a cattle-gun murder or an attack on protestors can be ethical so long as it is truly in accordance with the desire of the actor? The police certainly are not giving ground relative to their convictions when they shoot into a crowd, and they are cowardly and delusional enough to believe that these crackdowns in service of Law and Order truly put their lives on the line — does this make them paragons of virtue?

In 1961, captured Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann professed that he had tried to live his entire life according to Immanuel Kant’s maxim, which Eichmann interpreted as the obligation to “be master of my free will and volition” by “organizing my life” “according to my wishes”. The following year, in his essay “Kant avec Sade,” Lacan pointed out that there is no way for Kant to prevent D. A. F. de Sade from installing his own perverse maxim as the categorical imperative (a point Lacan had been making since Seminar VII in 1959), because the degenerate marquis presented the ethical duty to maximize selfish pleasure in a way that was unconditional, generalizable, and “apathetic”. In fact, the Lacanians argue that the Sadean commandment to enjoy has been installed as a categorical imperative in the form of consumerism, the moral obligation to make yourself an instrument of the Invisible Hand by pursuing pleasure in the form of commodities.

Here is the fork in the road between my ethical perspective and the skeptical position. The skeptic argues that there is no way out of this dilemma Eichmann and Sade impose on Kant, their discrediting of the empty formalism of Kant’s deontology, because any ranking of desires or determination of duties could only base itself on a baseless First Principle, an arbitrary subject-dependent object raised to the sublime level of the Freudian “das Ding”. Kant’s explicit object was his personal conception of the Highest Good, attainable only in the Christian afterlife. But Lacan argued that he implicitly posited another object, which he was forced to “send off into the unthinkability of the Thing-in-itself” in order to seamlessly merge the Will with the Law: the “voice of Reason,” the “voice of the conscience,” which Kant was far too Enlightened and prudish to associate with the voice and desire of God, as so many others do, determined as Kant was to maintain that “his God is faceless,” incapable of the bitter passion attributed to Him by Christian mystics like Jakob Böhme. Sade, too, conjured the voiced desire of a Big Other to authorize the actions of his ethical subjects: the monstrous instructions of Nature. While Kant wanted to use the disembodied voice of Reason to bring his desire into alignment with his Law, in service of his vision of “virtue and happiness,” Sade wanted to use the sinister Call of Nature to bring his Law into alignment with his desire by presenting the “transcendent wickedness” of ecstatic passion as the Highest Good.

And why not? If there is no ethical truth, the source and content of a moral law obviously provide no insight into the truth-value of that law. A theory of ethical subjectivation that makes it a duty to freely decide to become the obedient instrument of a mythical Other (Chance, Reason, Nature, the Fatherland) might lack some internal consistency, but this is of no concern to the skeptic. If The Good does not truly exist, if life and subjectivity have no inherent value, if the universe would be neither better nor worse were both to blink out of existence, then every moral law, consistent or otherwise, is just a deeply-held opinion. Therefore the claim that “capitalist exploitation and social oppression are ethically acceptable” is neither universally true nor universally false, in the same way that a simple statement of preference like “chocolate is the best flavor of ice cream” is neither universally true nor universally false. The ethics-atheist can strongly disagree with a justification of exploitation and oppression, but they cannot call it “false”.

Dispiriting as it may be, there is nothing illogical about the skeptical position. But if it is true that living beings and subjects, which both objectively exist, are the only possible sources of “good” things, that a universe in which life and subjectivity have emerged is “better” than one in which nothing is different from matter, then there is a bridge to cross David Hume’s is-ought gap between ontology and ethics, because there is an objective guideline for determining the ethical status of a decision, consequence, or moral character: does it serve the transcendent conjoined-twin Causes of life and subjectivity? This guideline is restrictive enough to be meaningful and useful but broad enough to allow for situational considerations which weigh the specific factors at work in a given case. An Ethics of Transcendence is the only basis that allows us to justify the claim that “exploitation and oppression are ethically acceptable” is an eternally-false statement, not just a provocative attitude or a questionable belief.

What about a religious condemnation of mistreatment? Moses was given a few messages to relay to the masses, among them: “You shall not oppress your neighbor or rob them” and “you shall love your neighbor as yourself”. Why? Moses is told: the Israelites must be holy “because I, the Lord your God, am holy”. Our duty is imitatio Dei. The Jewish religious tradition locates The Good of life, subjectivity, and the physical universe (“light is good”) in God, but unlike the existence of life and subjectivity, which is certain, the existence of God is not certain, and must be predicated on a leap of faith. Faith in lack-less God’s guarantee of goodness is the ultimate foundation of right conduct, abandonment of that faith is Evil, and justification comes much later, perhaps after we die, maybe not until the world-ending Messianic Redemption, when the secrets woven into the celestial curtain spread before God’s throne will be revealed. “All that the Lord has spoken,” the wandering Israelites called out in unison, “first we will do, and then we will understand [na’aseh v’nishma]”. Ours is not to reason why, ours is but to do and die — we are nothing more than the temporary instruments of the Divine Will. The “ethics” of religion is wholly immanent to faith in God, which means religion can only answer ethical questions through recourse to theology — an entirely different discourse involving entirely different conceptions of Truth and subjective power. Like it or not, in the search for a universally-true ethical foundation, these are your only viable options: the void, transcendence, and the substitution of theology for ethics.

If we forge forward with an affirmation of ethical truth, Lacan’s Ethics of Desire will be necessary but insufficient. For a subject to act ethically, they must first refuse to allow authority figures to determine their actions, but without a valorization of transcendence, there is no non-arbitrary reason for this resistance, and there is also no non-arbitrary basis for claiming this resistance should or should not take any given form. The subordination of the desires of the individual to the dictates of the State is bad because the universal freedom to desire is good. Rather than reducing ethical values to corresponding individual desires, as the sophists would instruct us to do, individual desires should be measured up to the ethical value of the ability to freely desire, which is the ability of every subject to maintain their own rapport with their subjective lack, free from the restrictions and manipulations of a society’s economic elites, its patriarchs, its dominant racial/ethnic group(s), all of its power structures interested in “enclosing” or “controlling” desire, as Deleuze warned us, through “molds” or “modulations”. Of course, the only way to be truly free of those structures is to annihilate them.

Why would one individual subject’s ability to desire be any more important than that of another? The freedom to act on your desire to destroy another subject’s ability to desire is not universal freedom; Sade acted on his desire by using his aristocratic family’s immense wealth and power to turn beggars, sex workers, and servants into objects of his pleasure. The capitalist can only act on their desires by robbing the proletarian of their ability to do the same. True freedom demands more than the rejection of the authority of an abstract Big Other — it also demands recognition of the subjectivity of the concrete “little other,” the other person. “Recognition” in the full Kojèvean-Hegelian sense of respecting and promoting the boundless Becoming of the other, not in the sense of that laughable “we hear you, we see you, we feel for you” liberal lip service. A universal expectation of mutual recognition is impossible in a society that reproduces itself by dominating the people assigned to subordinated social categories and by turning the people assigned to the proletariat into instruments of profit-generation for the capitalist elites. Fanon wrote: “I acknowledge one right for myself: the right to demand human behavior from the other”.4 In addition to this one right, Fanon added: “I, a man of color, want but one thing: may man never be instrumentalized. May the subjugation of man by man — that is to say, of me by another — cease.”5

When he was attacked by an angel, Jacob wrestled with him through the night, and refused to release the angel at dawn unless he gave him a blessing. Because Jacob struggled and prevailed, the angel was forced to grant him a new name: Israel, etymologizable as “he triumphed over God”. Jacob’s righteous victory demonstrates the ethical justification for rebellion — we all possess one right as subjects, the right to have our subjectivity recognized and not infringed upon, and violent struggles like the one Fanon participated in, the Algerian War of Independence (which influenced Lacan’s analysis of Antigone’s heroic intransigence), can sometimes be the only way to ensure that our right is respected. It is a bitter historical irony that righteousness resides not on the side of the modern nation-state that bears the holy name that Jacob earned but on the side of the rebellion against it.

The recognition granted to Jacob in the form of a new name finds a contemporary echo in the right of transgender people to be recognized by the name and pronouns that they select in accordance with their “strategy of Being,” as Lacanian psychoanalyst Patricia Gherovici phrased it. The affirmation of a gender identity that contradicts the one assigned to you at birth is a good example of what can be called “Lacanian virtue ethics”. What makes the cultivation of ethical subjectivity Lacanian is its dual nature — the war must be waged on two fronts. The fatal flaw of Herbert Marcuse’s Ethics of Desire was his failure to recognize that the direct interference of The Powers That Be, the set of moral dictates which he called the “performance principle,” is not the only threat to the subject’s ability to desire freely; the subject is, before anything else, the subject of the unconscious, and the desire of the subject is, before anything else, the desire of the Other. Contra the fear that “if there is no God, everything is permitted,” Lacan repeatedly suggested that “if God is dead, nothing is permitted” — the restrictions and punishments our unconscious encourages us to impose on ourselves are no less repressive than the rules of the Church and State.

The unconscious functions as the locked boiler room of the subject, a set of automatic mechanisms and structures that respond to the Real ontological lack at the core of the subject by accumulating and processing the Imaginary and Symbolic material piped in from the outside world, condensing and displacing inoperative signifiers into effectual meanings, and organizing and releasing excess excitement and enjoyment through its pumps and radiators. This dynamic, invisible labyrinth facilitates the conscious and rational operations of the subject, but its power is a double-edged sword: the unconscious provides the subject with autonomy from their social environment, separating cause from effect, but its consistency traps the subject in an endless loop, Hegel’s “bad infinity”. Out of the frying pan of hard determinism and into the fire of the repetition compulsion. The unconscious teaches the subject to identify with the same prefabricated web of signifiers, chase the same chain of socially-constructed objects of desire, and wait for the same rushes, again and again. As if that programmed monotony were not bad enough, the unconscious also operates through deception: Kant’s voice of Reason — the angel on your shoulder — is a fraud, the superego in disguise, the cop in your head, ordering you to hate yourself.

However, even if we can never escape or master our unconscious, we are not doomed to drift through life as its helpless puppets. According to Mari Ruti, my favorite contemporary critical theorist, “psychoanalysis presupposes that we can productively intervene in the disclosure of our destinies”.6 For Ruti, the practical value of Lacanian psychoanalysis lies in its capacity to help us “transition from merely having a future to having a say in how that future is to be lived,”7 and the process she describes — the transformation of a passive existence decided by our social and unconscious history into an active, self-determined existence — is the only path to achieving a virtuous character. Alenka Zupančič is more of a Kantian and Orthodox Lacanian than Ruti, but they agree on the question of the possibility of ethical agency; Zupančič argues that the decision of the subject “subservient to their unconscious” to simultaneously “choose their unconscious”8 is the “forced choice” which serves as the “psychoanalytic postulate of freedom”.9

In 1960, Lacan presented Antigone as the supreme ethical figure because she never wavered in her decision to elevate her object-cause of desire to the level of the Highest Good, the only good. For the sake of her brother’s corpse, an object that she transformed into a sublime embodiment of her royal family’s honor, she became inhuman, sacrificing every other desire, every possible social and personal good. Through her tragic, fatal commitment to this desire, Lacan claimed that Antigone had incarnated “pure desire”. But his thinking changed after the French revolts of May ‘68 and his subsequent study of Marx,10 and he began his 1972-1973 seminar, Encore, by expressing dissatisfaction with his earlier Ethics of Desire and analysis of Antigone, which were too distracted by Beauty, by Antigone’s reified splendor, to plunge all the way forward into ugly Truth (“beauty is truth; truth beauty,” John Keats wrote, incorrectly). Over the final decade of his life, Lacan pushed through the barriers of blinding images and enchanting symbols to finally confront the maddening Real (and judging by the rabbit hole of Charlie-Kelly-esque formulae and diagrams that it sent him into, the Real succeeded in driving Lacan insane). This confrontation allowed him to theorize an Ethics of the Not-All, which posits an ethical obligation to admit to your lack, to stop lying to yourself about your limits, to rid yourself of your comfortable illusions of completion and dominance, and, most importantly, to create Gherovici’s “strategies of Being” — which Lacan called “sinthomes” — through a series of conscious and rational subtractions, additions, and alterations to the array of positive images, identifications, and values that orbit the pure negativity at the core of your Real self.

Deploying Late-Career Lacan’s advancements, clinical psychoanalyst Sophia Papadopoulou refuted Mid-Career Lacan’s Romantic assertion that Antigone’s desire to “preserve the myth of Oneness” through the neverending pursuit of a “beautiful object” that “constitutes the Other as whole” could be truly considered “pure”.11 Then Papadopoulou revised the conventional Lacanian reading of Antigone, contending that Antigone, condemned to die, abandoned by her gods and her people, actually experienced a crisis of faith and confronted the futility of her particular desire, “devaluing this crown that supported her desire for so long,” “transgressing the limits of her fantasy,” “killing the object of her desire,” and “getting rid of the possibility of becoming, once more, the victim of an illusion”.12 If we accept Papadopoulou’s interpretation of the play (which I consider to be more useful than convincing), Antigone purifies her desire and becomes an ethical subject precisely by wavering, successfully transforming her self-understanding by taking the object of her moral law down from its pedestal, rejecting her former faith in a lack-less Other, and separating herself from the identifications and values handed to her by the Labdacid dynasty. Friedrich Schlegel wrote that “we must elevate ourselves above our own desires and be able, in thought, to annihilate what we adore, otherwise we lack the sense for the infinite” — Papadopoulou’s Antigone gains a sense for the infinite when she elevates herself above her own desires and annihilates them.

If Lacan is correct that “it is the law of the relation of the subject to themselves that they must make themselves their own neighbor as far as their relationship to their desire is concerned,” then ethics requires that we get to know our neighbor, but instead of unconditionally loving them, we may need to kill them. The ethical status of a subject’s desire is determined by the real impact it has on them and on other living things and subjects, but it is also determined by the desire’s relation to the Real; it is wrong to live, fight, and die for lack-denying, Truth-less abstractions like Honor, Glory, and modern ruling-class ideologemes: the Free Market, the White Race, Bourgeois Democracy. Rimbaud wrote that “our desires lack an inner music”; we cannot write the notes from scratch, but we can compose new melodies. To become virtuous, detach your desires from the imperious, fictitious laws of the Other and dictates of the unconscious and submerge those desires in the positive and negative substance of subjectivity — your own and the lowercase-o other’s.

Self-transformation starts with self-destruction, but if you want to avoid Antigone’s fate, it cannot stop there. The thirteenth-century Jewish mystic Abraham Abulafia wrote that the aim of Kabbalistic practice is to “unseal the soul, untying the knots which bind it,” and this is a perfect description of the first step in the struggle to transcend the unconscious. But once the knots are untied, the subject experiences destitution, “the crack-up,” flickering between infinity and the void, an unsustainable state. We dissolve without something to cling to, something to lend us coherence. Novalis wrote that “the ‘I’ is fundamentally Nothing… Everything must be given to it”. Accordingly, Novalis urged us to create “necessary fictions,” self-unifying Highest Principles that can serve as an “Absolute foundation” for our subjective Being, even though they are “something invented, something devised”. We cannot last unless we invent our own durable, artful mediators between our fundamental Nothingness and Everything we are exposed to. This is the source of the strength of the bond between the Jews and the Torah.

The ultra-aggressive Assyrian Empire had already conquered the Aramean Kingdoms, the Kingdom of Urartu, the Hittite city-states, and the Kingdom of Babylon when it invaded Samaria, destroyed the recalcitrant Northern Kingdom of Israel, and deported its educated elites in 722 B.C.E. Those displaced Israelites are now thought of as the “Ten Lost Tribes,” but this is a myth — many of the Samarians simply joined their estranged, isolated cousins in the less-advanced Southern Kingdom of Judah. The cosmopolitan and diverse Northerners, cut off from their roots, participated in the production of the early religious texts that would form the basis of the Torah, and their theological efforts to explain their devastating military defeat infused Judean thinking with vitality and breadth [a general dynamic that has arguably defined the contributions of the Jewish Diaspora to non-Jewish philosophy]. The disaster the Samarians experienced, however, was only the forerunner of the potentially-fatal blow dealt to the Israelites several generations later, when the Kingdom of Babylon reclaimed its independence from the Assyrians and launched its own imperial expansion campaign. In 586 B.C.E., the Babylonians crushed a Judean revolt, razed the city of Jerusalem, demolished Solomon’s Temple, and exiled the country’s upper class.

Bereft of political and geographic unity, the Israelites faced dissolution. If they could not build a collective body capable of resisting the forces of social entropy, they would melt into their world. What differentiating factors could prevent them from suffering the same fate as their neighbors, who lost their distinct identities after their respective states were destroyed by regional superpowers? The Israelites spoke a Northwest Semitic language, worshipped a Canaanite religion, and practiced circumcision — all of that also held true for the Moabites (conquered by Babylon, assimilated into Arabian tribes), Ammonites (disintegrated when the Assyrians stopped protecting them from desert raiders), Edomites (lost their kingdom to the Babylonians and Nabataeans, later forced to convert to Judaism by the Hasmonean Dynasty), and Phoenicians (dissolved after the Greeks and Romans conquered their city-states). The Israelite faith was no more reliable than that of their extinct rivals. The God of the Bronze Age Patriarchs, “Ēl/Elohim/El-Shaddai,” was a standard Canaanite deity spanning all the way back to the Ancient Ugarits, a paternal creator-god at the head of the pantheon worshipped by the other ill-fated groups in the Levant. Yahweh, who gradually and ambiguously merged with Ēl in Israelite consciousness, was introduced to the Hebrew-speakers at the beginning of the Iron Age, possibly by the Midianites, who lived in the deserts southeast of modern-day Eilat. Just like their neighbors, it was not uncommon for the Israelites to create icons depicting their God, as well as His wife, the maternal fertility goddess Asherah, the Queen of Heaven in all of the Canaanite belief systems, associated with sacred trees of life, traceable to the Ancient Sumerians, who depicted her as “Ishtar” in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Despite the efforts of centralizers like King David and King Josiah, the Israelite religion was thoroughly pluralistic, not monotheistic, prior to the Babylonian Exile. Even those statesmen were not arrogant enough to ask their people to purify themselves of belief in the existence of other gods — all they wanted was for the Israelites to refuse to give ground relative to Yahweh. This prioritization of one supreme national god did not make the Israelites special, either: they were Yahweh’s chosen people, just as Kemosh was the patron deity of the Moabites, Milkom was the patron deity of the Ammonites, and Qos was the patron deity of the Edomites.

When they were deprived of the objective or “empirical” unity that comes with geopolitical power, the broken Israelites transcended their unremarkable origins and recomposed themselves through remarkable subjective or “metaphysical” bonds — words, beliefs, institutions, and rituals designed to construct and reproduce a durable communal identity. The completion and transmission of a standardized written canon in the years following the destruction of Judah was a revolutionary transformation of collective self-consciousness that pulled the obsolete Israelites back from the brink of the abyss by giving them a future as Jews. The intellectual leaders of this endangered group worked together to craft a sturdy, coherent, monotheistic Jewish subjectivity out of the material provided by their people’s customs, cultural memories, ancient legends, and political history. As Bertolt Brecht said, “nothing comes from nothing; the new comes from the old, but that is why it is new”.

The old pantheon was compressed into a single, unifying/unified deity: “Hear, O Israel [Shema Yisrael]! Yahweh is our God, Yahweh alone/Yahweh is one”. The old elements which did not promote the harmony of the new system were purged or repressed — Queen Asherah can be discerned in Eve, the “mother of all the living,” in the sacred trees of the Garden of Eden, and in God’s Shekhinah, the “Great Mother,” the feminine attributes of His divine presence. An elegant and intuitive solution was found for the problematic co-existence of Ēl and Yahweh — the authors of the Book of Exodus (a story that promised the Jews that they could survive exile) wrote that God told Moses: “I am Yahweh. I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El-Shaddai, but I did not reveal my name, Yahweh, to them”. Before the Babylonian invasion, God’s image was depictable, His name was not taboo, and it was taught that He was physically manifest in the Holy of Holies as a cloud of glory. But after the destruction of Solomon’s Temple and the crisis of faith caused by the defeat of both Israel and Judah, a radical revision of the people’s relationship with their deity was in order. The letter and the voice were to replace the icon and the statue; the resilient signifier triumphed over the fragile image. God’s earthly presence became much more “faceless,” as Lacan phrased it, much more abstract and spiritual. His name could only be alluded to, not spoken (HaShem, a common title Jews use to refer to God, literally means “The Name”). It was explained that the loss of God’s own country and temple could not diminish His strength, because He is fully transcendent and immaterial, too powerful to represent in a name or an anthropomorphic figure, impossible to contain within the limits of an ark or a nation. Where you are, He is; God and His teachings are universal and eternal, exceeding any and all historical-particular boundaries. And the Jews, like their God, could be confident that they would withstand geographic dispersal, military defeats, and political collapse, because their strength came not from their physical proximity, common gene pool, or State power — factors which failed to keep their neighbors intact — but from their shared texts, values, congregations, and practices. Fidelity to this self-conception has allowed the Jews to maintain our identity in the midst of chaos and catastrophe for the last 2,500 years.

/

/

/

Is my conception of The Good too diluted, too of-this-world? My theory of transcendence primarily comes from the Kabbalistic Vitalists, but as it pertains to the natural world, I am closer to F. W. J. Schelling than to Oskar Goldberg and Erich Unger — I do not share their mystical disdain for “corporeal reality”. Alain Badiou does. In Badiou’s Gnostic arrangement, human bodies are husks, valuable only to the extent that they serve as containers for pneuma. While I value life itself, Badiou values humanity insofar as it strives for the Absolute which the Gnostics associated with Sophia, who was the female personification of God’s wisdom, an idea the Early Christians took from Kabbalah, which positions wisdom as the second divine attribute, the feminine Sefirah “Hokhmah”. In a poem entitled “Three Rendezvous” (1898), Russian philosopher and Spinozist-Hegelian mystic Vladimir Solovyov recounted his supernatural visions of Divine Sophia, who gave him the power to become something more than “this vain world’s captive,” stuck in an “illusive” realm of “mundane things,” by allowing him to “sense the glow of the flawless mantle” “underneath matter’s coarse shell,” enabling him to “triumph over death” and “vanquish time”. Badiou’s goal is also to escape mundanity and become something immortal, something eternal, and even though he would not follow the voluntarily-celibate Solovyov in asserting the necessity of “becoming forever blind to earthly joys,” Badiou enjoins us to resist becoming the captive of the hylic “enjoyable life”. It seems to me that this is the most logical position to hold for a person who has devoted their life to the search for infinite truths, whether their quest takes the form of philosophy or mysticism. Badiou wants us all to join him on the path to transcendent wisdom, and he sees vitality (which he distinguishes from worthier affects like love, enthusiasm, and joy) as a potential obstacle; avec Sade and Kaczynski, Badiou is quite pessimistic about “human nature” — he believes that the human animal, the human as nothing more than a “living being,” is “in reality contemptible,”13 a “systematic killer” which “pursues interests of survival and satisfaction neither more nor less estimable than those of moles or beetles”.14

The interests that Badiou considers to be estimable are the interests of subjectivity, but not subjectivity as I have presented it. I have conflated the subjectivity of the individual, which Badiou refers to as the “psychological subject,” with political subjectivity and collective subjectivity in general. Unfortunately, the desiring subject-of-lack “falls within the province of human nature, within the logic of passion,”15 and Badiou holds the natural and the irrational in contempt. He is driven by the same “sense for the infinite” described by Schlegel, and he believes that the only infinity available to life itself is a dirty semblance, Lacanian “jouissance,” destructive, meaningless, excruciating pleasure, the plane connecting Eros to Thanatos. Badiou distances his chaste Platonic subject from the lascivious, pleasure-seeking human animal as conceived by Sade, who can only understand infinity in terms of an Absolute Zero of ceaseless ecstasy. In Sade’s Juliette (1797), Saint Fond imagines an Anti-Messianic end-time in which the “monstrous molecules” that constitute human nature “assemble” for a demonic Redemption that Lacan characterized as “spintrian jouissance,” the painful enjoyment of the sphincter, Sade’s favorite example of extreme, unbearable pleasure completely divorced from reproductive and “rational” purpose. For reasons Badiou has failed to properly justify, this experience is of zero value to him — perhaps he never tried it. Badiou is looking, for right now, to stimulate the pro-State versus anti-State political antagonism, and his top social priority is always the subject’s immortal power; bottom position on his list is assigned to simple pleasure, no matter how versatile it may be.

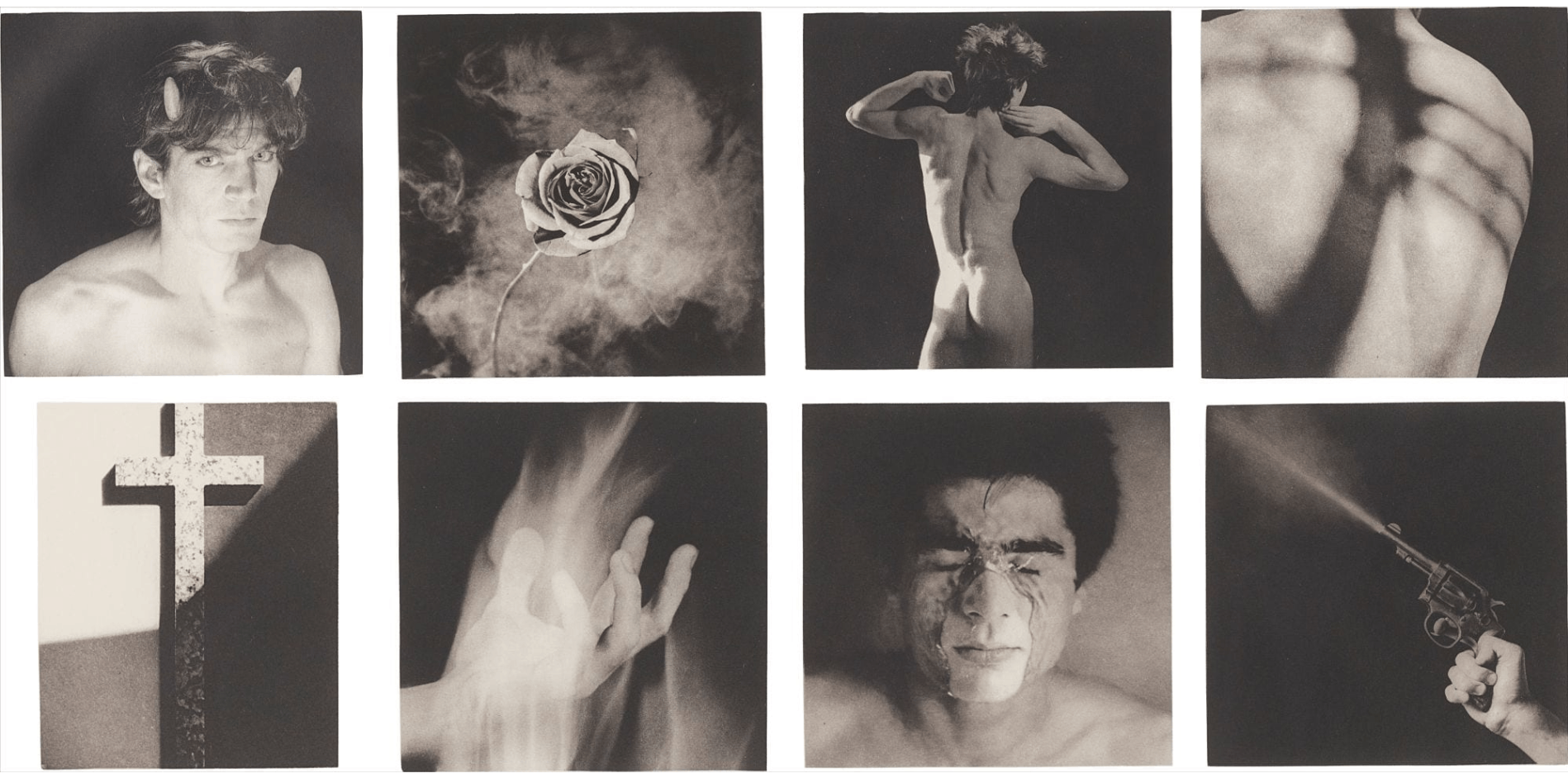

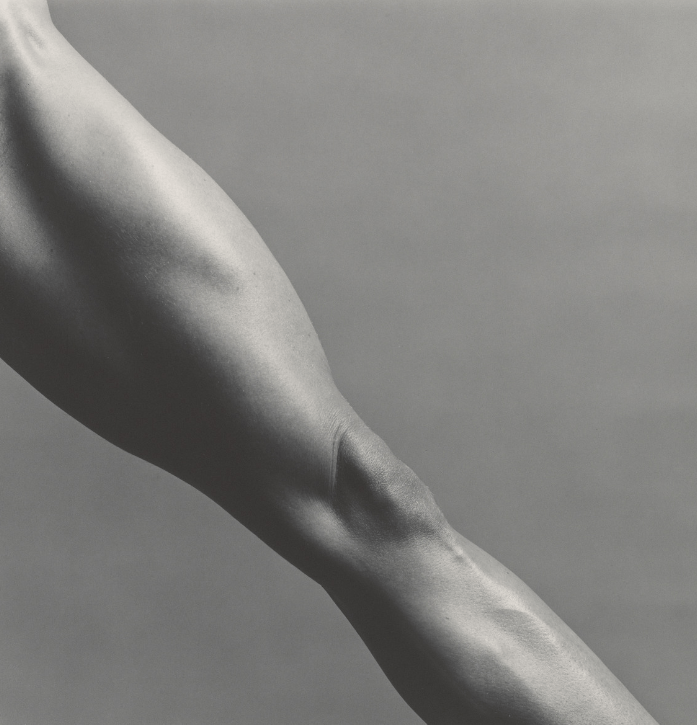

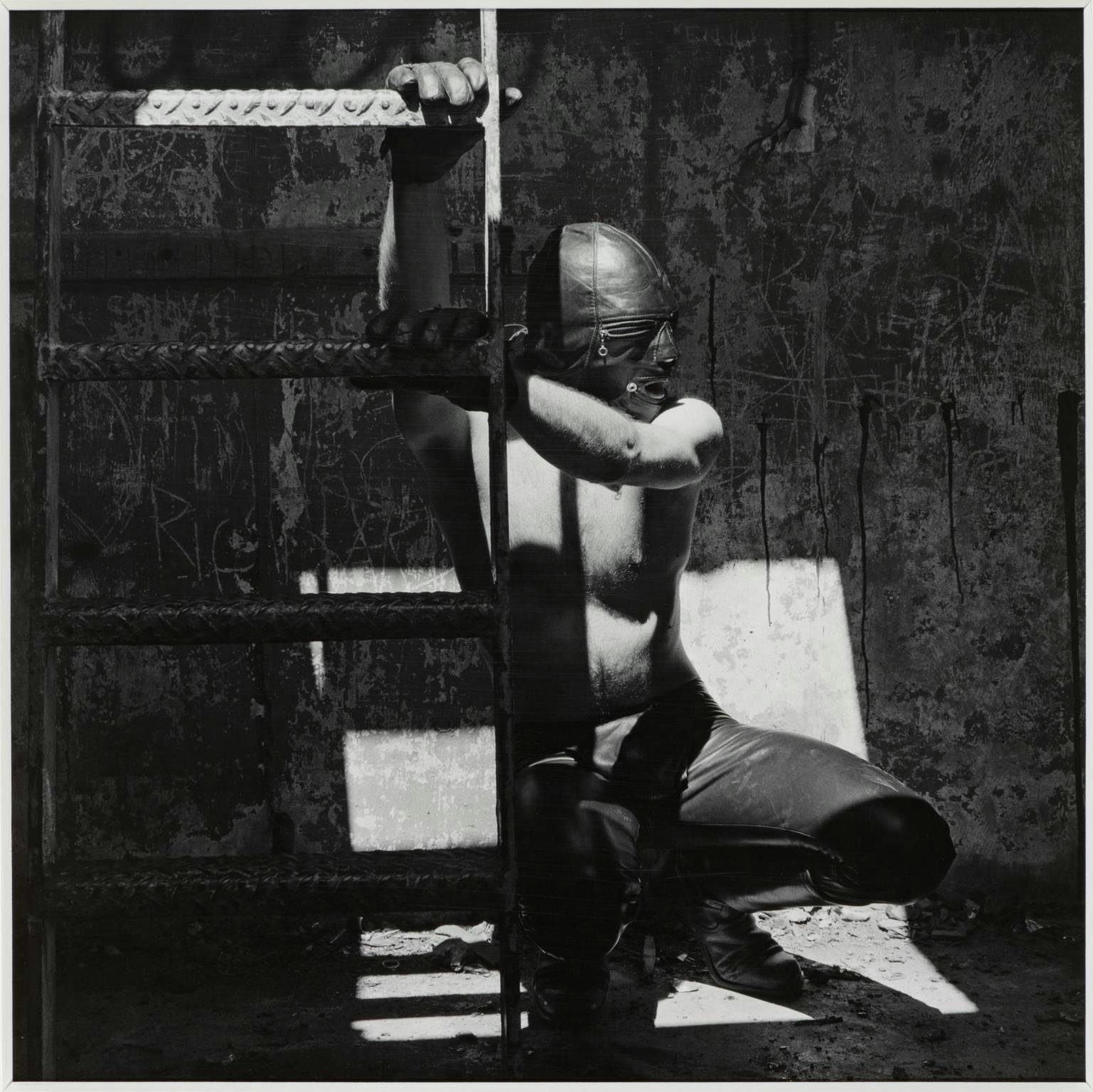

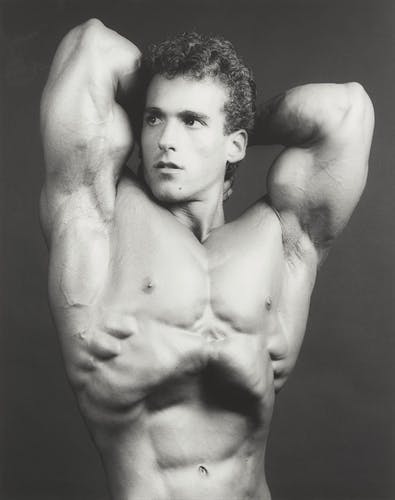

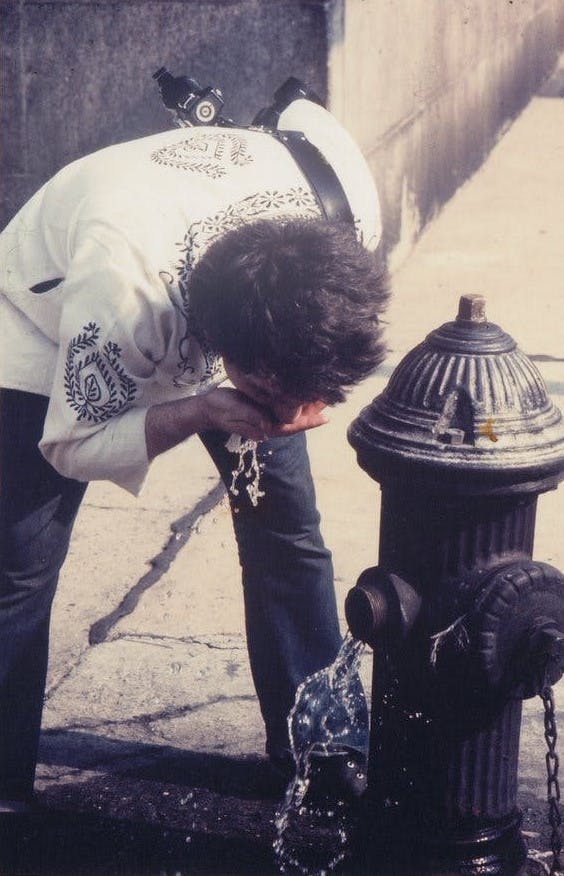

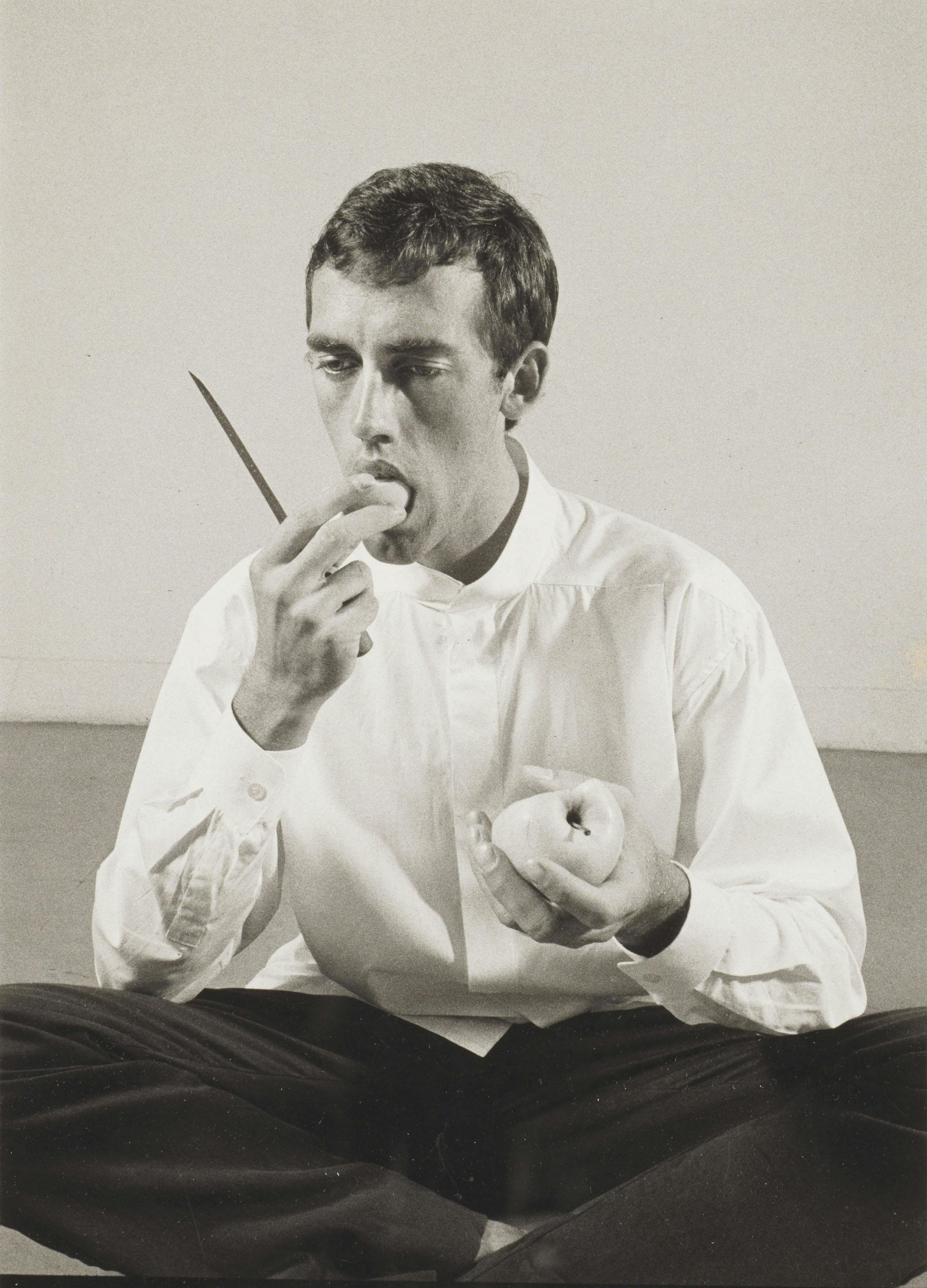

Puritanical or not, it is impossible to deny that Badiou’s anti-hedonism holds some water when you consider the example of the “radical” desire-enshrining photography of Robert Mapplethorpe [“Mapple” is pronounced like the syrup; an irrationally-spelled last name, something I can relate to]. In the 1970s and 1980s, Mapplethorpe became a celebrity by making High Art out of the lurid New York underworld of gay sexuality. At the end of his unhappy adolescence, Mapplethorpe re-enacted Rimbaud’s flight from suffocating, conservative, Catholic suburbia into the libertine avant-garde of the metropolis, where he was free to experiment with his art and his sexuality.

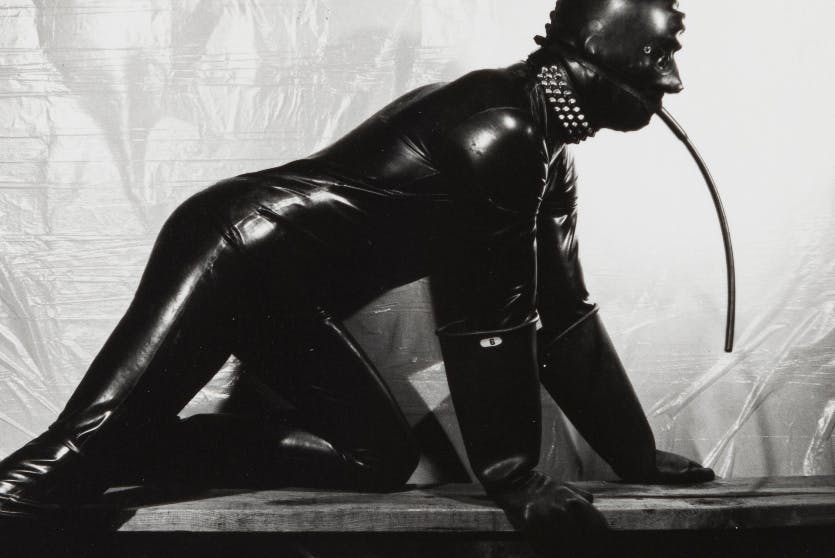

Throughout his career, Mapplethorpe attempted to shock and outrage the repressed, squeamish society that raised him by violating its sexual taboos, celebrating the desires it designated as transgressive, and spotlighting the explosions of jouissance that Nixonite-Reaganite America considered the most disgusting and obscene.

Unlike Rimbaud, he did not produce art that could stand the test of time, but he did succeed in provoking controversy and profiting off of his sacramentalization of profane sex acts. The lawmakers and advocacy groups of the white Christian Right fought to prevent his photographs from being exhibited and the white Sophisticated Bourgeoisie showered him with praise, attention, and money — after he died, his estate was worth $228 million. His apolitical narcissism was perfectly compatible with the conception of individualistic sexual liberation that proliferates among bored, open-minded urban elites. For Rimbaud, libidinal and cultural liberation were inseparable from collective political liberation, as evidenced by his Messianic vision of “harmony undone” by the “fiery whirlwinds’ fury” in “Blankets of Blood” (1872) — a poem shaped by the ephemeral revolutionary victory and hellish counter-revolutionary slaughter of the Communards — which called for a “march of vengeance,” “blankets of blood and golden flames,” “war and terror” brought down on the “industrialists, princes, senators, and emperors” by the global forces of humanity in order to create a world where the masses are freed from repression and toil; Mapplethorpe enjoyed drinking expensive champagne and eating beluga caviar with literal European princes and princesses at his haut monde cocktail parties, staffed by armies of black-jacketed waiters and hosted in his vast, lavish Manhattan loft-studio. You could make the case that Rimbaud’s “Sideshow” (1874) anticipated this “grim onslaught of pretense” — Mapplethorpe fits that poem’s description of a “self-satisfied” man “in no hurry to devote his faculties to understanding another’s mind,” exclusively interested in “heading to town to take it from behind, all decked out in sickening luxury”. His glorification of subversive desires disrupted harmony only in order to force the ruling class to acknowledge him. Mission accomplished.

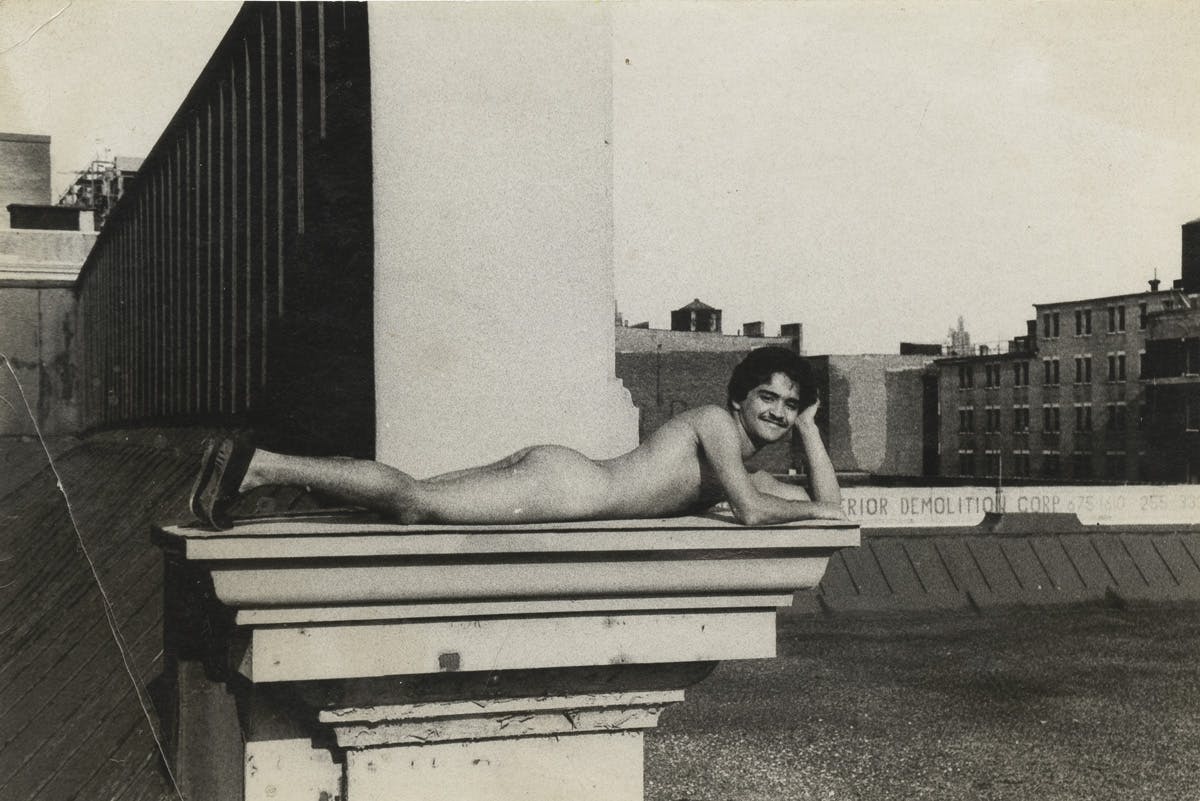

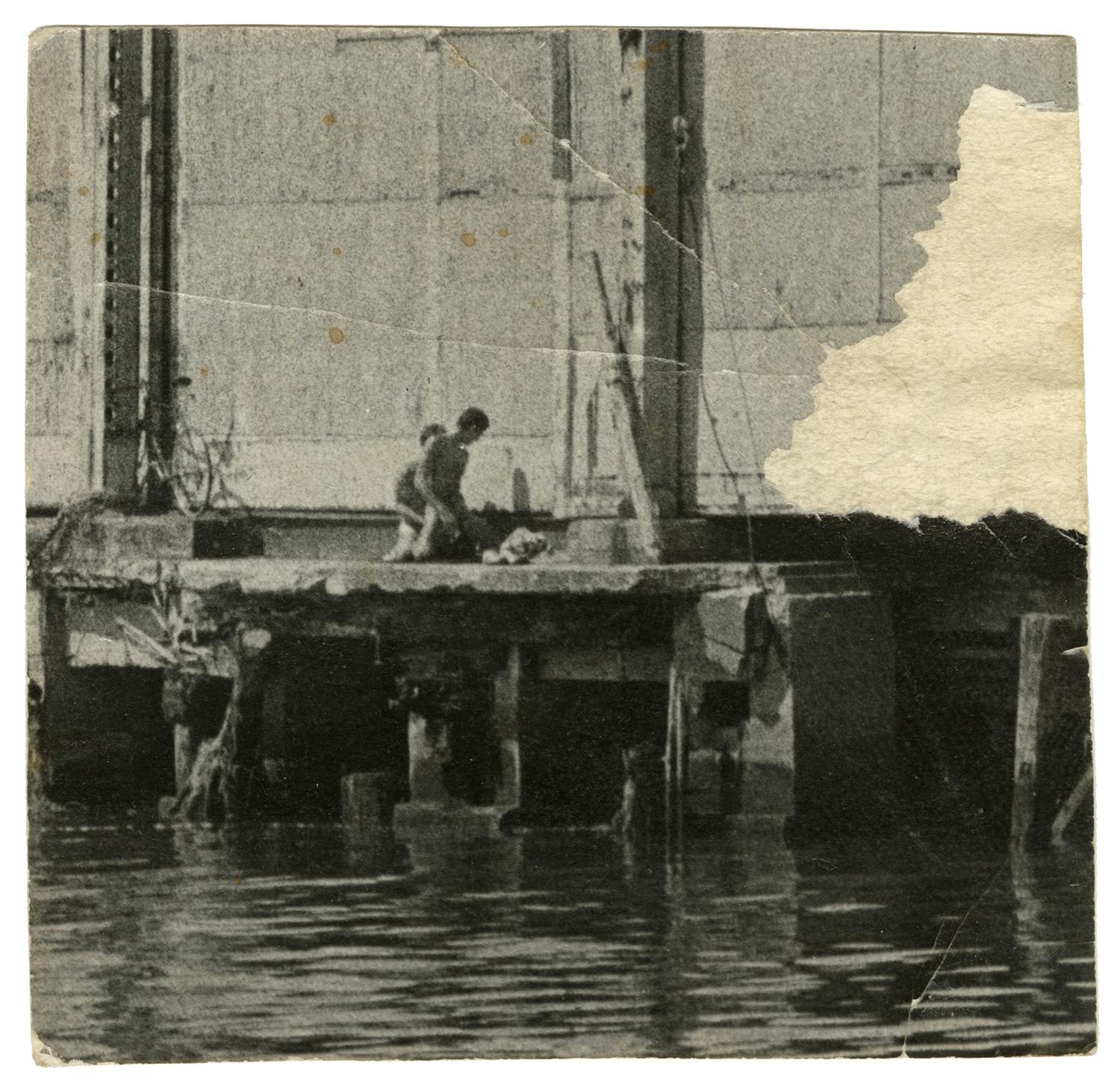

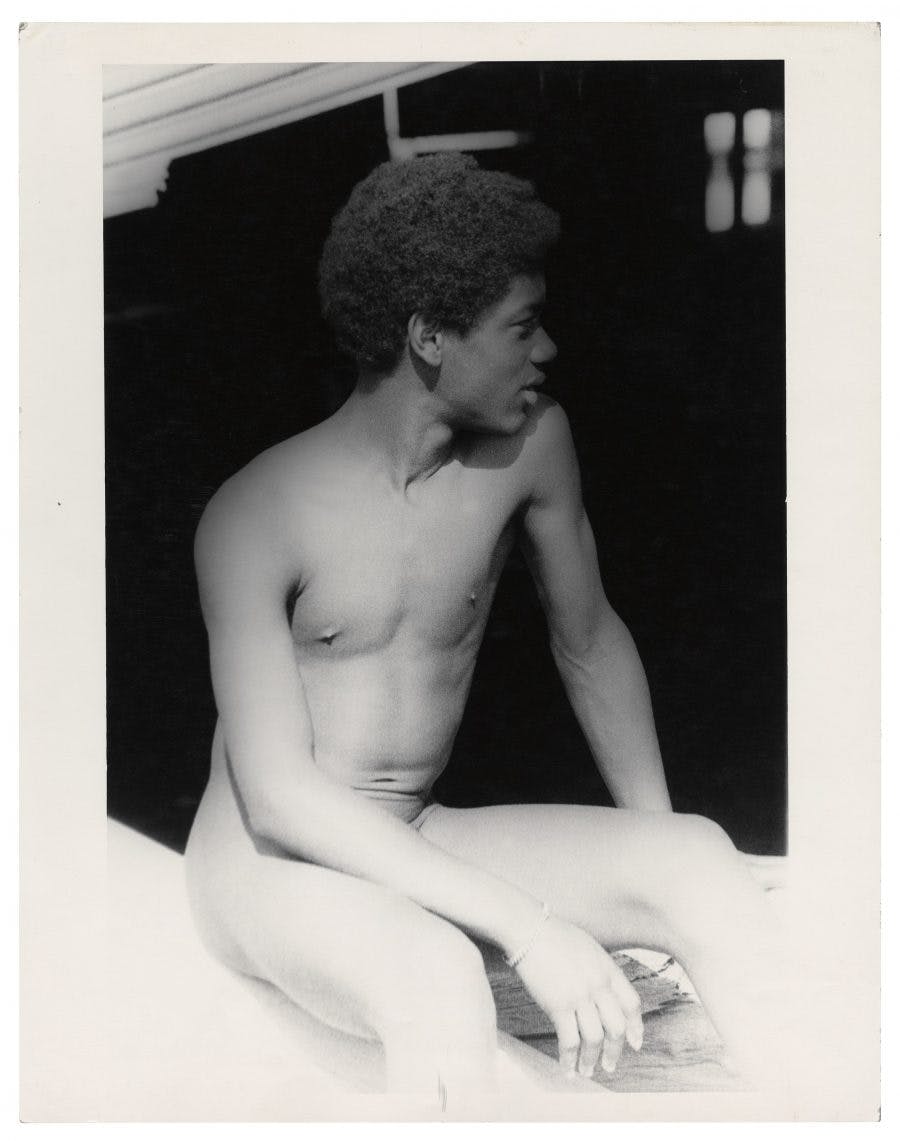

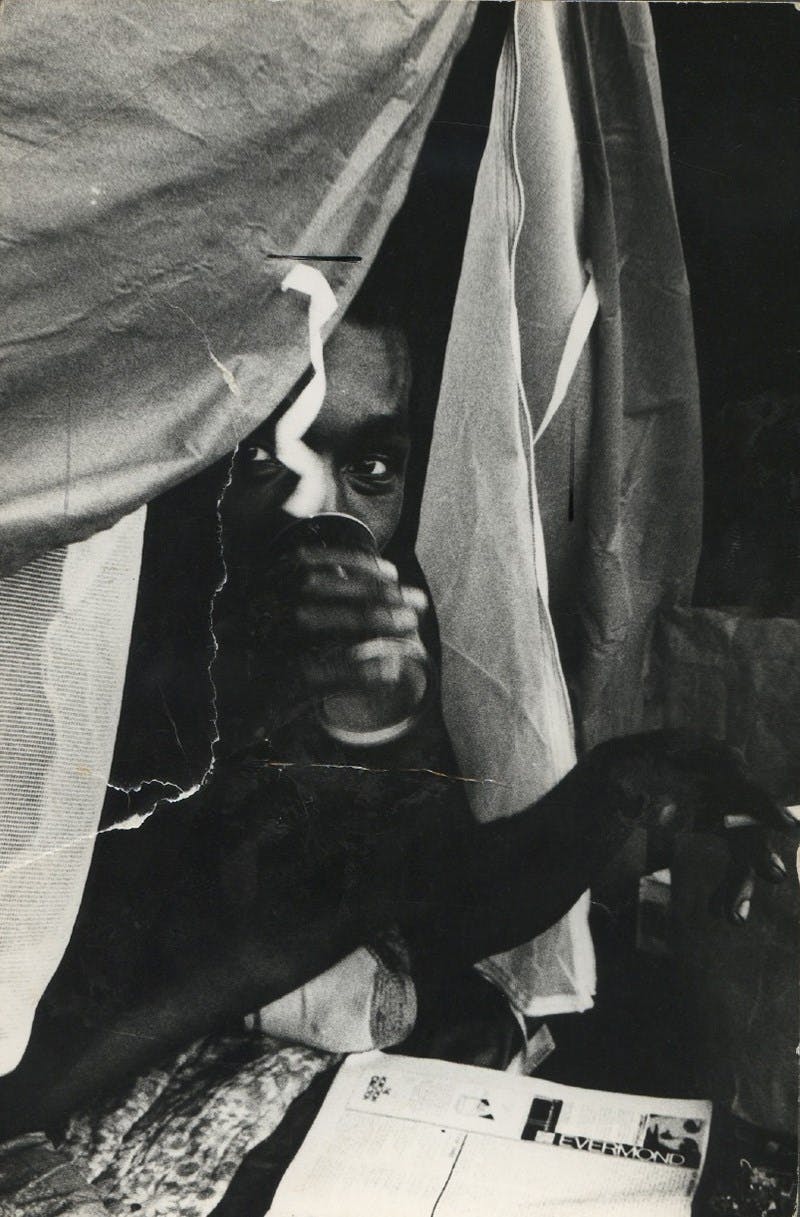

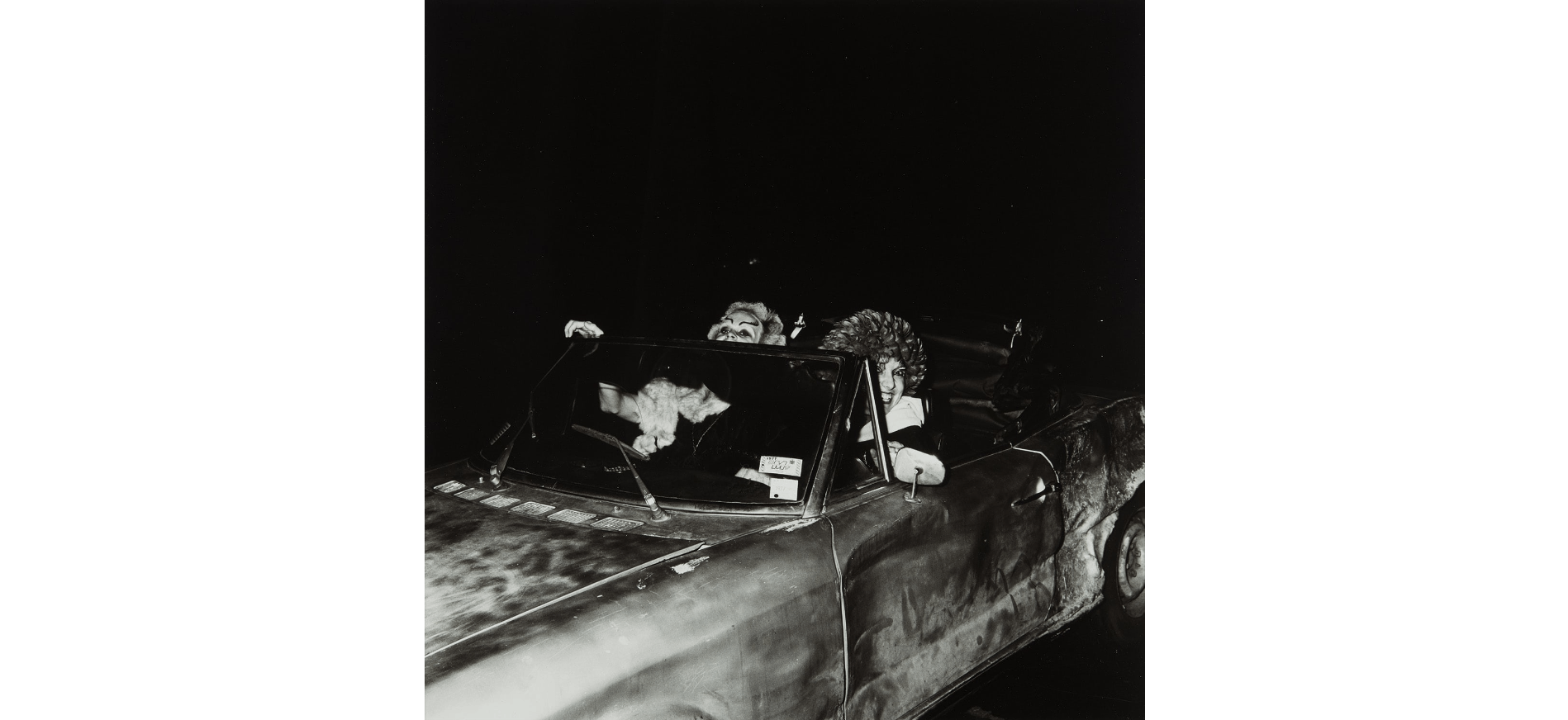

Mapplethorpe is a notch in Badiou’s incorporeal-transcendence column, but I will try to even the score with a counter-example: the art of Alvin Baltrop, another bisexual man (although he considered the term “bisexual” to be too politically correct) who escaped from an intolerant Christian home and spent his twenties and thirties photographing the hidden realm of gay sexuality in New York in the 1970s and 1980s. The similarities stop there. Mapplethorpe confessed that the identities and lives of the models whose bodies he transfigured did not matter to him, which is why his art is false; Baltrop’s art is authentic because he knew and cared about the people who appeared in his photographs.

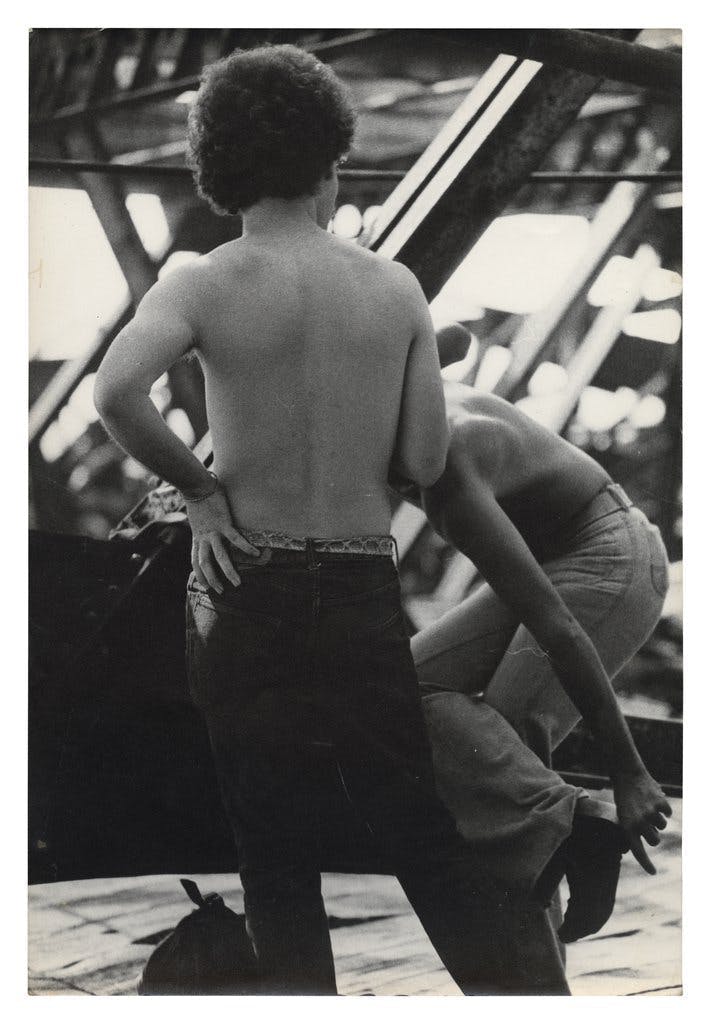

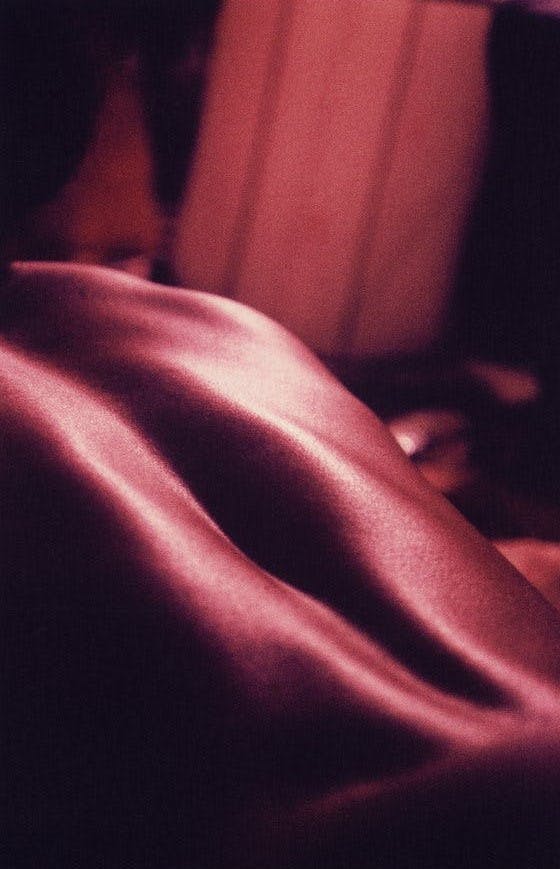

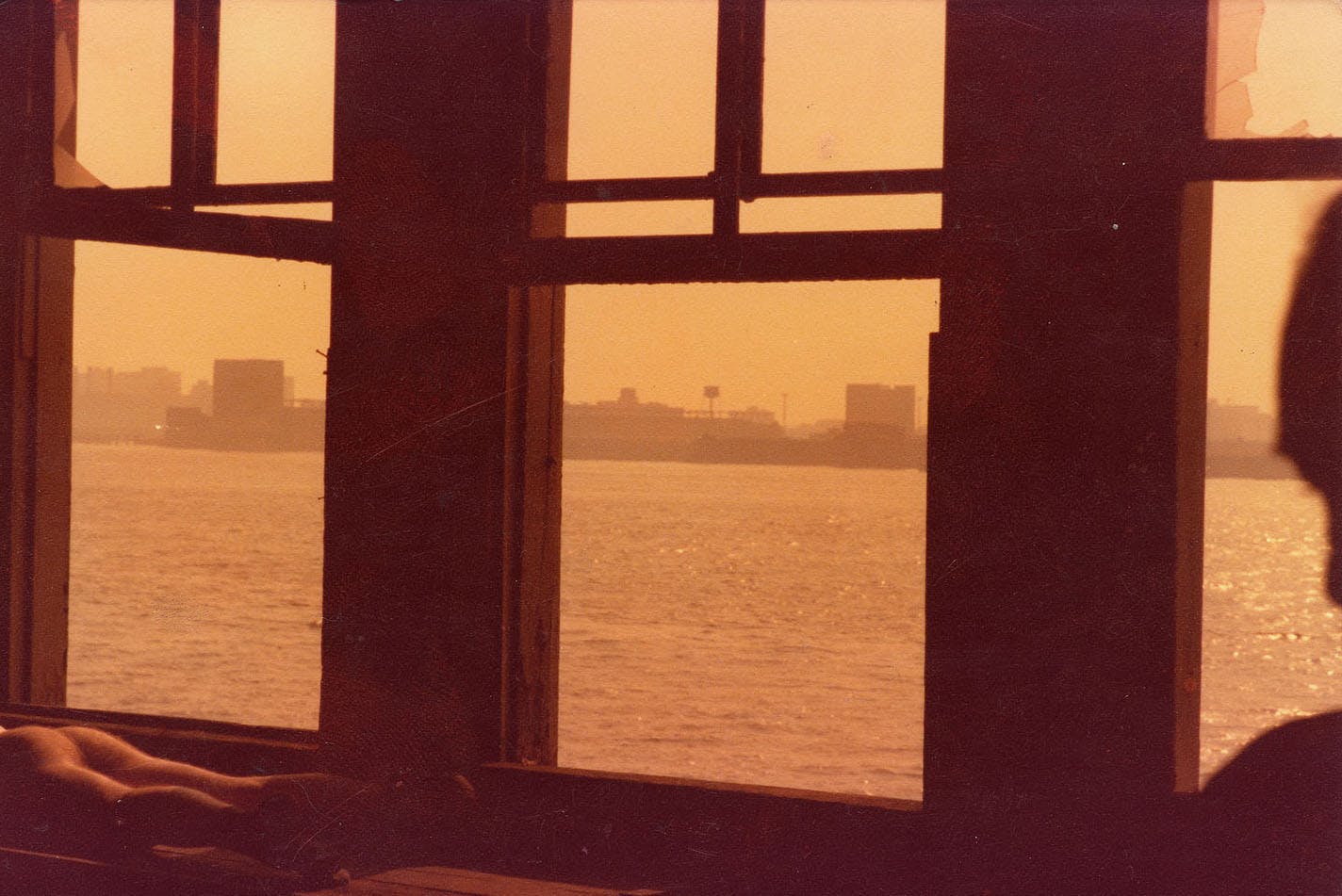

Baltrop did not want to be the master of ceremonies at a well-attended freak show, nor did he want to use sexual rebellion to turn his life into a commodity à la Lola Montès (1955); Baltrop wanted his art to “tell the truth,” a truth he formulated when he was 21: “in the dark we all can be free”. His pictures reveal the transcendent dimension of corporeal reality by treating sexual freedom as a means for human connection, warmth, intimacy, and joy rather than stripping desire down to its purest, emptiest, inhuman form.

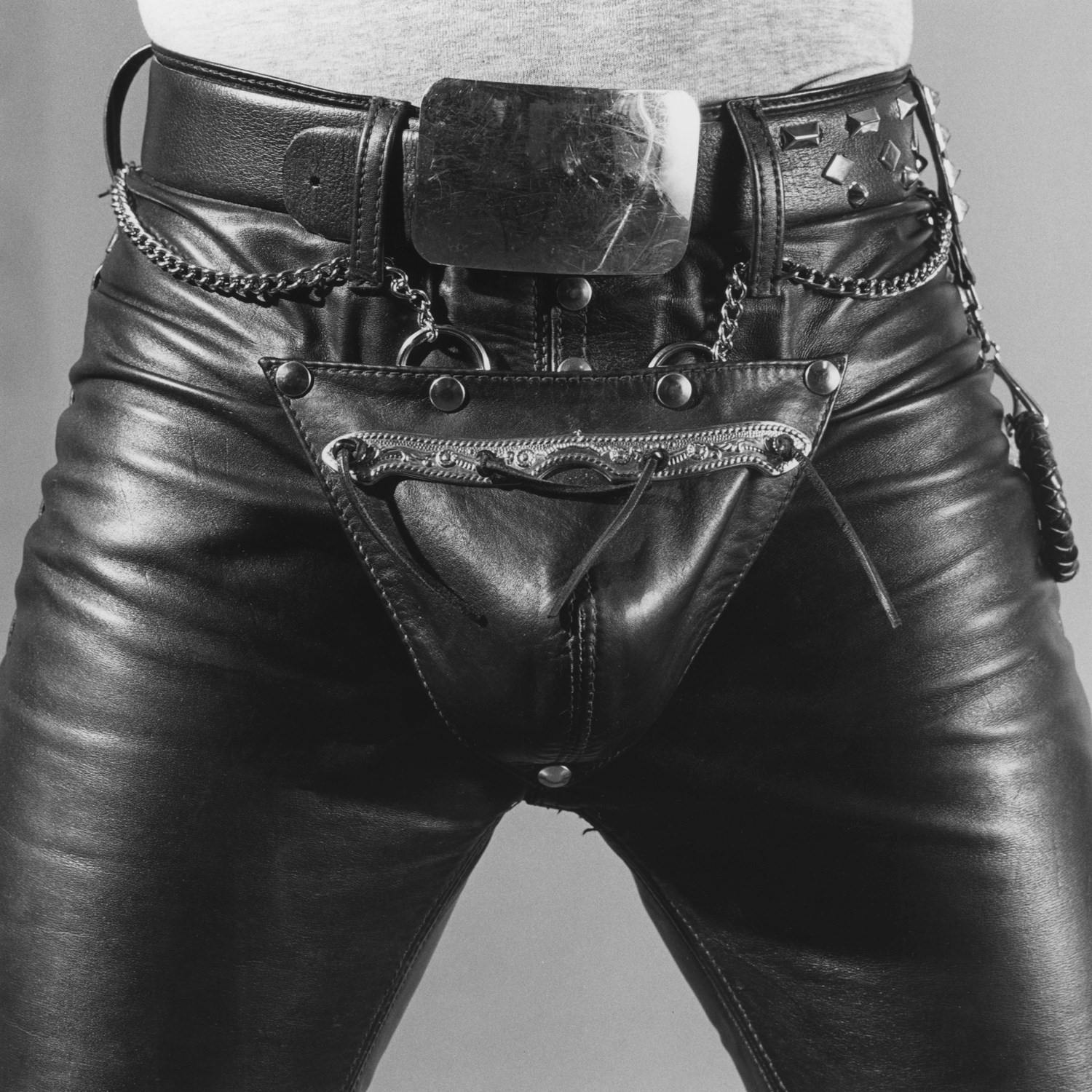

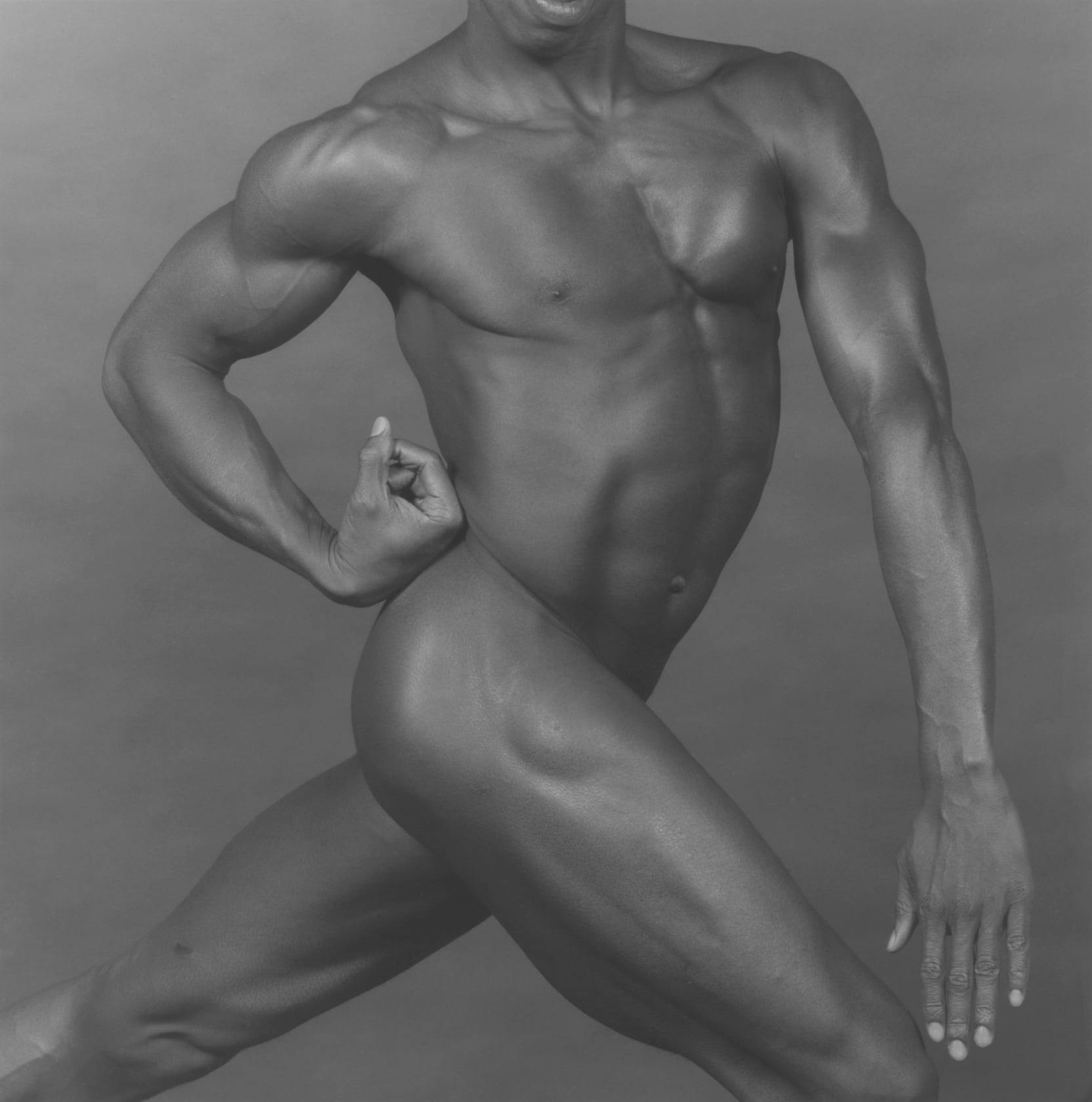

Vampiric Mapplethorpe was solely interested in the fetishistic, meaningless dimensions of desire, desire for its own sake. He cherished the aesthetic beauty of the body, the shock-value of gay sexuality, the boundaries of sado-masochistic jouissance.

In Seminar VII, Lacan placed jouissance under the sign of Evil because of its cruel and aggressive character and its link to the suffering of the other. In his Écrits (1966), Lacan referred to the “misadventure of desire at the hedges of jouissance, watched over by an evil god”; Mapplethorpe urged his sex partners to push past pleasure into the domain of jouissance by repeating the phrase “do it for Satan”. Baltrop, on the other hand, was interested in sexual desire not as it pertained to jouissance and taboo but as a means of appreciating the good aspects of the experiences and relationships of the human animal. Baltrop linked the body with the life it sustains, conceived of gay sexuality as a communal sphere of outcasts seeking comfort in each other, and tested boundaries because the shared thrill was invigorating.

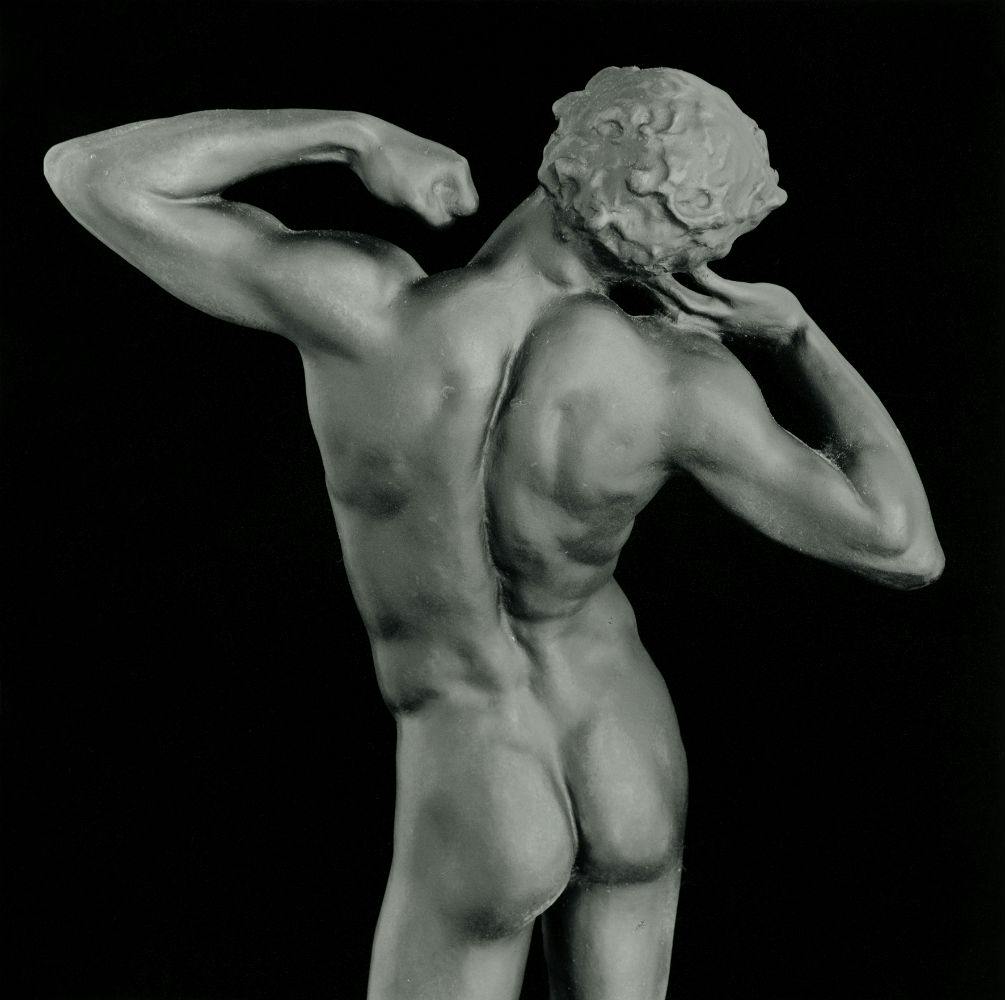

Mapplethorpe’s idea of beauty was cold — a flawless statue, a perfect sex object, an ideal physical specimen.

Baltrop saw beauty as highly-charged, quivering with sensuality and emotion — the affection involved in sex, the camaraderie of transgression, the will to enjoy life together in a time and a place pervaded by suffering and decay.

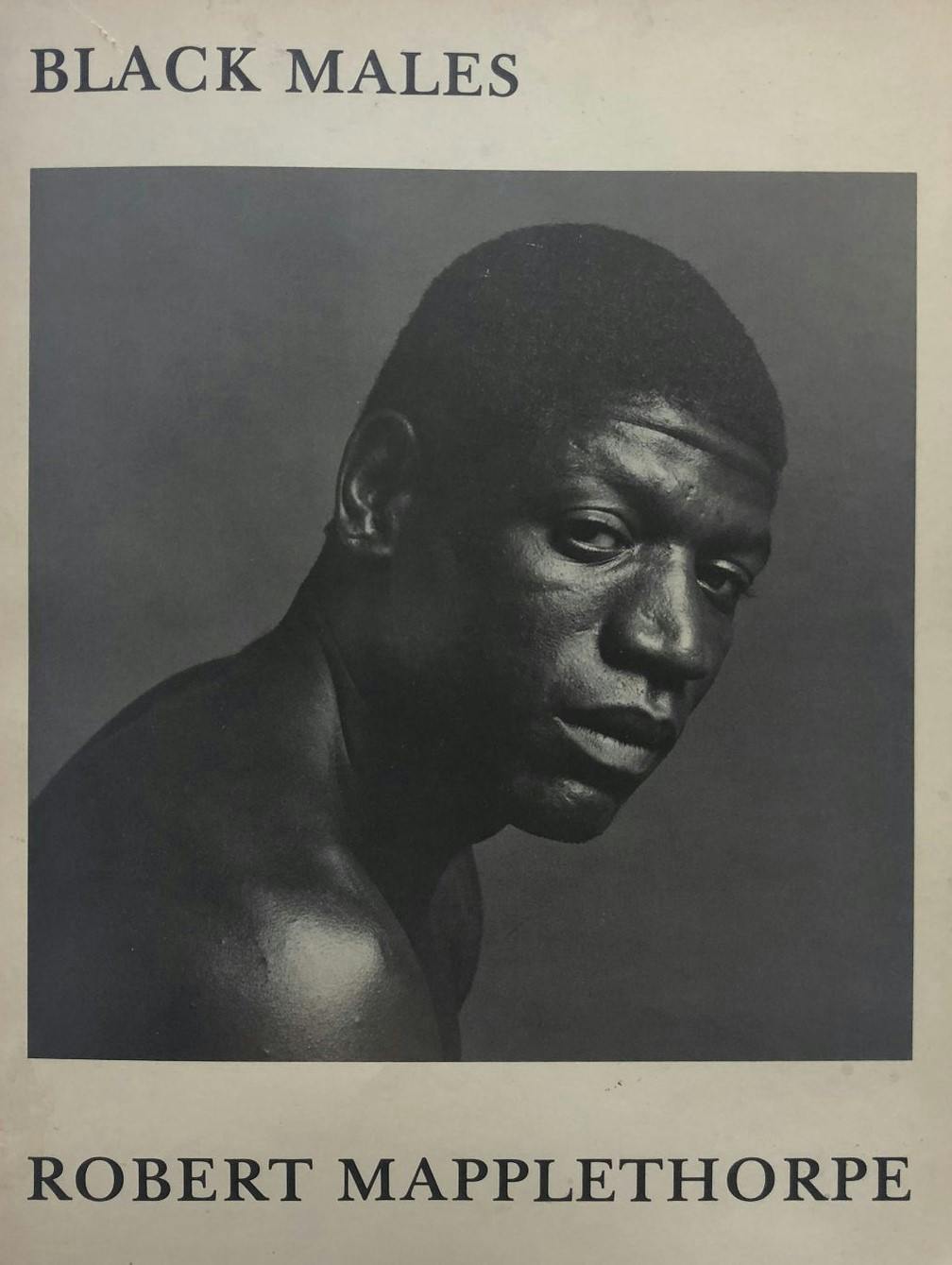

The artists’ divergent capacities for compassion and empathy toward their subjects can be at least partially explained by America’s dynamics of racial privilege, super-exploitation, and exclusion. Mapplethorpe was an extremely racist white man who used the bodies of gay Black men to fulfill his dehumanizing fantasies of primitive, potent Black masculinity.

Baltrop was Black, which prevented him from achieving the critical and commercial success that Mapplethorpe enjoyed.

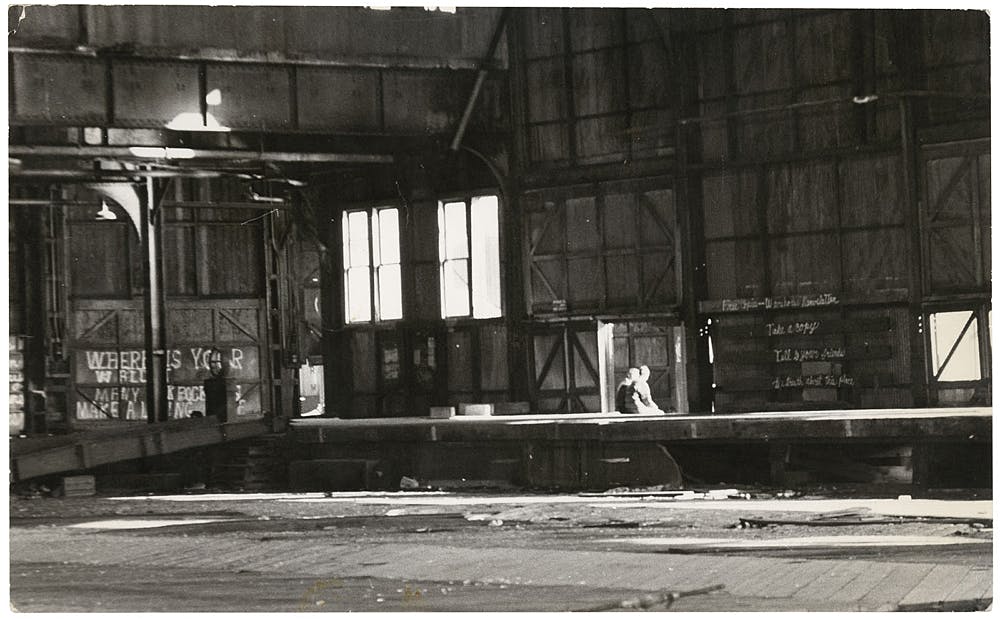

Some gay white gallery owners insinuated or outright alleged that Baltrop must have stolen the photographs in his portfolio from white artists — one white art curator called him a “sewer rat”. Mapplethorpe’s exhibitions drew large crowds and media buzz; Baltrop had to resort to anonymously plastering reproductions of his photos onto the city’s surfaces. The ultra-wealthy Mapplethorpe’s typical modus operandi was to use his fame and access to drugs to lure the attractive Black men he met at clubs back to his professional studio, which was purchased for him by his well-connected art curator sugar daddy. Baltrop — who struggled to pay rent and cobbled together a living as a cab driver, a bouncer, a street vendor, a mover, and a printer — photographed his subjects as they were and where they were, typically on and around Manhattan’s abandoned westside piers, which were then a place where the LGBT underclass could freely (but not safely) socialize, escape from abusive parents, sunbathe, produce art, and have sex.

Mapplethorpe was excited by the social construction of homosexuality as subversive; Baltrop’s photography reported on the devastating consequences that this designation had on the homeless teenagers whose families kicked them out because of their abnormal desires, even as he also uncovered the delights available to those who do not abide by the paradigms of gender and gender relations propagated by their ruling class, who refuse to give ground relative to their desires in service of the prescribed “normal life”.

While Mapplethorpe tried and failed to unlock transcendent desire by severing the vulgar erotic from its mundane living context, Baltrop succeeded by uplifting the erotic sparks of transcendence hidden within vulgar life. Like Rimbaud, both of them lived fast and died prematurely — Mapplethorpe died of AIDS at the age of 42, at the height of his renown, cared for around the clock by a team of nurses he boasted of paying $1,000 a day; Baltrop died of cancer at the age of 55, in obscurity, after receiving inadequate medical treatment because he could not afford health insurance.

Mapplethorpe’s body of work demonstrated the limits of the life of the individualistic pleasure-seeking human animal through the photographer’s unwillingness to maneuver the contradiction John Cheever described as “the imperfect joining of the carnal world and the world of spiritual matters,” but this does not mean that Badiou is correct to view carnality as worthless when set side by side with spirituality — it can go both ways, so to speak. Cheever, whose struggle with the contradiction between his aberrant bisexual desires and his Christian desire for discipline and grace caused him great suffering, added that in the longing for spiritual purity at the expense of corporeal enjoyment “there is a lack of space, of latitude, of light and humor”. Baltrop discovered this light by exploring a space where people merged their carnal desires, augmented their enjoyment with the enjoyment of another, and combined their finite bodies to create moments of infinity.

Alain Badiou values the combination of bodies only when their entanglement gives rise to an infinite collective body animated by an eternal Truth, a transcendent Idea. Desperate people giving each other pleasure do not possess the type of power Badiou is after. Many members of Baltrop’s underground LGBT community fused their belief in liberatory sexuality with militant, radical, universalistic political organizing, but only the latter matters to Badiou. For him, recreation and relief will always pale in comparison to Truth; an individual can realize their Badiousian subjective power not by transforming their relationship with their own body and the bodies of others but by deciding to “become one of the elements of another body,” a more metaphorical body, “the body-of-Truth”.16 The Badiouisan subject participates in Truth — lowly human animals become immortal subjects when they use “their bodies, their abilities… to enable the passing of a Truth along its path”.17 An individual person is worthless, because “each individual, the ‘anyone,’ is only an interchangeable animal,”18 but they can become something transcendent if they are willing to “declare that they can go beyond the bounds (of selfishness, competition, finitude…) set by individualism (or animality — they’re one and the same thing)”.19

Badiou’s anti-humanist devaluation of the “mere life” of the individual must be placed in the context of the two key philosophical occurrences that his thought reacts against — the mass defection of defeated radical intellectuals to the side of the status quo in the 1970s and 1980s, and the prevalence of liberal humanitarian justifications for imperialist intervention in Yugoslavia, Iraq, and Afghanistan in the 1990s and 2000s.

After the Cultural Revolution in China and the May ‘68 movement in France both failed, the vast majority of Badiou’s European comrades — disconnected from the surging national liberation movements in Vietnam, the Philippines, Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and Mozambique — abandoned the struggle for a new world and returned to their comfortable lives as professional academics, artists, and psychoanalysts. Magical rapturous youth gave way to the placid, barren middle-age made available to highly-educated professional workers by French colonial wealth. “Now once more the belt is tight and we summon the proper expression of horror as we look back at our wasted youth,” wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald, an expert on the misery and nastiness of (male) subjective deactivation if there ever was one. Many French intellectuals took advantage of the capitalist media’s interest in discrediting revolutionary politics through the gleeful and lucrative publicization of the testimony of former radicals who “grew up” and realized the error of their ways. A procession of sneering renegades lined up to cash in on their newfound maturity by confessing to their sins, mocking the grand ideals of their soixante-huitard youth, expressing embarrassment and bewilderment at having been caught up in the moment, and pledging fealty to their reasonable, stable, and satisfying social order, which might not be perfect but is still the “least bad” system. The traitors coped with their self-betrayal by heaping praise on the meaningless way of life that they had chosen over the increasingly-hopeless life of a French revolutionary communist.

Badiou’s entire career as a philosopher can plausibly be summed up as a response to this betrayal, an adherent’s negation of the apostates’ negation. It is not for nothing that Badiou’s motto is the final line from Rimbaud’s “Blankets of Blood”: “I am there, I am still there”. The French intellectuals who abandoned their posts pinned the blame for their “abdication of subjectivity” and their decision to “settle down for a life of order” on the “failure of the rebellious mass movement of May-June 1968,” but Badiou’s thinking begins with his claim that the true cause of their loss of subjectivity was their “failure to hold themselves steady,” their willingness to be “put purely and simply back into their place”.20 To relinquish subjectivity and return to the service of bourgeois-imperialist “goods” is to “deny the Immortal in myself,” “the Immortal that calls on me to continue,” to hold “the becoming-subject in myself” steady.21 During the historical nadir of communism, the lonely decades following the collapse of the French and Chinese mass movements, Badiou held steady, refusing to betray himself by renouncing the infinity of revolutionary subjectivity. Instead, he upheld a “Promethean Ethics,” which posits an obligation to serve as the “faithful guardian” of the flame of communist politics during a Thermidorian era, to “keep the Becoming of courage while running on empty” in defiance of the triumphant capitalist class.22

The traitors abandoned grand narratives, beliefs, and Causes in favor of humble observations, common sense, and the competent maintenance of the current situation. Badiou responded by identifying unlimited and universal Truth as the source of the infinite value of subjectivity. In his philosophical system, Truth materializes as the consequences of a transcendent “Event,” Badiou’s name for an irruption of novelty from the void of a situation, an extraordinary “return of the repressed” which exposes the previously-obscured social Real and points the way toward an entirely-different situation. His subject enters into Being as the Becoming of the Truth of an Event. You can move beyond the “temptation of wanting-to-be-an-animal” and participate in the transcendence of Truth through your “fidelity to the Event,” the pledge you make to fasten yourself to the Real rupture within your situation, the promise to remain loyal to the piercing invalidation of prior knowledge and belief. The Good is defined as a disruptive opportunity to achieve transcendence, an “internal norm of a prolonged disorganization of life,” any interruption of the status quo that enables a person to consistently exceed their finite “life as a socialized human animal”.23 Evil is sorted by Badiou into three categories: a simulacrum of Truth (the faux-revolutionary trappings of Italian and German fascism), a betrayal of the Immortal that you are (the people who renounced their participation in May ‘68), or a dogmatic, ultra-purist, purge-happy failure to recognize the inevitable limits of our ability to recognize Truth (Stalin’s Moscow Trials). Ordinary deprivation and violence, situated by Badiou in the Animal Kingdom and thus removed from the celestial combat in his transcendent realm of the fidelity and Truth of the subject, cannot be considered “evil,” because “every life, including that of the human animal, is beneath Good and Evil”.24

The other major historical stimulus for Badiou’s anti-humanist ethics was the propaganda vomited out by the liberal shills for imperialist warfare, particularly the War on Terror. The serious thinkers of France, England, and the United States in the 1990s and 2000s defined The Good in terms of “Western values”: humanism, human rights, and humanitarianism, realized through democratic principles, economic freedom, and social equality, leading to political stability, economic growth, and advanced civilization. Evil was defined as barbarism, dictatorship, and hatred, realized through terrorism, totalitarianism, and fundamentalism, leading to chaos, backwardness, and the creation of victims in need of an imperialist savior. Humanitarianism conceives of the ethical subject as a Helpless Victim, the ethical political act as imperialist intervention, and the Highest Good as the comfortable Western lifestyle: a hedonistic, careerist, alienated, meaningless, powerless existence. Badiou conceives of the ethical subject as the principled militant, the Highest Good as a true life lived in accordance with a transcendent Idea, and the ethical political act as the destruction of capitalism, imperialism, and State power.

Against the self-congratulatory bourgeois image of the desiring subject satisfied by their solid career, air-tight nuclear family, and abundance of affordable commodities, Badiou says that the subject “in no way pre-exists” a Truth-Process, is “absolutely non-existent in the situation before an Event”.25 The human animal is not a subject by virtue of its vitality or its desires, nor does it become a fully-fledged subject through the active Rutian-Lacanian sinthome-fashioning process that I have outlined. Badiou’s theory of the creation of the subject comes from his personal political awakening, which was triggered by the brutality and injustice of the French war against Algerian independence, and from his experiences during the May ‘68 uprising, a rupture that, he wrote, “uprooted my prior existence as a minor provincial civil servant” and sent him “towards a life submitted, ardently submitted, to the obligations of militancy,” a submission that came “not from a lucid decision, but from a special form of passivity, from a total abandonment to what was taking place”.26 This dialectic of “ardent militancy” and “passive submission” has been present in the modern concept of subjectivity since it was first theorized by Kant — as Étienne Balibar has explained, the term can be traced to both the subjectum who is the “agent of individual properties” and the subjectus who is “subjugated to law or power”.27

Against the “vacuous” proponents of human rights and the sentimental protectors of mere life, Badiou defends the anti-humanism of the twentieth-century radicals who believed that “the world can and must change absolutely; that there is neither a nature of things to be respected nor pre-formed subjects to be maintained,” and therefore “the individual is not independently endowed with any intrinsic nature that would deserve our striving to perpetuate it”.28 Discussing The Decision (1930), a play by Brecht, Badiou justifies the eponymous decision that the story’s Communist Party cadres make to kill their young troublemaking comrade for the sake of their revolutionary mission, ratifying “the idea that the individual can be sacrificed to a historical Cause that exceeds them”.29 By breaking from the collective subject that gave him meaning and value, Badiou claims that the agitator relinquishes his claim on immortality, and thus the choice to kill him in order to prevent him from jeopardizing a workers’ uprising was “cruel” but not evil.30

Walter Benjamin also refused to valorize the “mere life” of the human animal. Giorgio Agamben has done some bizarre and specious things with a passage from Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence” (1921) concerning the “sanctity of life,” but Benjamin’s point was straightforward: life itself is not more valuable than justice, which means that the destruction of life in the struggle for a just existence is defensible. Attacking the Lebens-philosophers and Bergsonian vitalists of his time, Benjamin wrote: “humans cannot, at any price, be said to coincide with the mere life in them,” and “there is no sacredness… in their bodily life, vulnerable to injury by their fellow humans”.31 The difference between the human in its existence as a vulnerable flesh-and-blood creature and the human in its existence as something that partakes greatly in the infinite is the key to understanding the endlessly-debated distinction Benjamin created between “mythic violence” and “divine violence”. Contemporary philosophers love coming up with their own little spins on his concept of divine violence: for Agamben, it is simply the inverse of Carl Schmitt’s theory of sovereign power; for Jacques Derrida, it is Benjamin’s futile attempt to fill the void of moral authority left behind by the revolutionary destruction of Law; for Slavoj Žižek, it is the pure violence of a riot, an enraged crowd blindly lashing out with no regard for laws or goals. Judith Butler, like so many liberal scholars before her, longs to defang Benjamin, in her case by diverting attention toward his discussion of non-violent conflict resolution, but Butler deserves some credit for actually paying attention to the anti-humanist context of the concept of divine violence — she recognizes the significance of Benjamin’s statement that “blood is the symbol of mere life” in explaining the non-transcendent nature of mythic violence, which Benjamin characterizes as “bloody,” “demanding sacrifice,” “bloody power over mere life for its own sake”.32 Mythic violence, which is State violence, preserves the power of the group of people who comprise an era’s ruling class by setting legal boundaries, issuing threats, and spilling blood. Divine violence is to the perpetrators of mythic violence what the tornado is to the characters in A Serious Man (2009) — a dark reminder that their concerns are insignificant on the cosmic scale. Divine violence belongs to no era or territory, preserves nothing, wastes no time with threats, and has no limits on its power, boundlessly striking without warning, continuing to strike until total annihilation has been achieved and a purer sphere has been inaugurated.

The Biblical example of divine violence that Benjamin cites is the story of Korah and his band of rebels, who are swallowed up into the earth without warning as a divine punishment for their mutiny, an act of violence that purifies the Israelite community and expiates the sinners. This is not a good example.

In Chapter 16 of the Book of Numbers, three Israelites — Korah, Dathan, and Abiram — lead a group of 250 dissidents in challenging the authority of their leader, Moses, and his brother, Aaron, their High Priest. Korah, the first cousin of Moses and Aaron, publicly confronts them: “You have gone too far! For all of the community are holy, all of them, and the Lord is in their midst. Why, then, do you raise yourselves above the Lord’s congregation?” Moses is so shocked and outraged by this reasonable criticism that he is reduced to slapstick comedy: the Torah says he literally “falls on his face”. Dathan and Abiram chime in: “Is it not enough that you brought us from a land flowing with milk and honey to have us die in the wilderness, that you would also lord it over us? Even if you had brought us to a land flowing with milk and honey, should you gouge out our eyes?” Another fair point, but God does not think so. The next morning, the ground under Korah, Dathan, and Abiram’s tents “bursts asunder,” sending the usurpers down into the underworld [Sheol]. After that, “fire comes forth from the Lord” and consumes the 250 other rebels. Then God sends a plague that kills 14,700 of the Israelites. With all of their rivals and critics wiped out and all of their surviving subordinates traumatized, Moses and Aaron emerge more powerful than ever.

The consensus among modern scholars is that this story weaves together two separate narrative strands that were composed/recorded at two different times: the uprising against Aaron’s priestly privilege led by Korah, and the uprising against Moses’ sole leadership led by Dathan and Abiram. The rebellion against Moses appears to come from the older of the two sources, written in the direct aftermath of the fall of the Judean monarchy. It is a cautionary tale against inter-tribal jostling for power, but above all the fate of Dathan and Abiram is a warning not to challenge the civil authority of political leaders, a warning probably authored by the scribes of the recently-exiled Judean royal court. The chapter’s other component, the blasphemy of Korah and his men, is most likely a product of the priests of the Second Temple, who considered themselves to be the direct descendants of Aaron. They would have intended the horrific immolation of Aaron’s challengers to serve as a threat against any Jews who questioned the power the priests had amassed after the Persian Empire allowed them to return to Jerusalem and construct a new temple.

Once we take into account the power-preserving agendas of the narrators and the passage of centuries between the completion of the texts and the events they claim to recount, how can we ever separate the divine Truth from the human myth? And if the Book of Numbers really does tell us exactly what happened that lethal morning in the desert, or at the very least gives us accurate insight into what God wants from us, then what basis is there to disagree with the evangelical Christian preachers who interpret every natural disaster as an act of divine violence intended to annihilate the gays?

Benjamin’s reference to Korah demonstrates the shortcomings of the concept of divine violence, a concept Benjamin would leave behind once he embraced dialectical materialism. The story that is supposed to differentiate the violence connected to God’s infinite moral authority from finite, pernicious violence only blurs the line between the mythic and the divine. Before his epistemological break, Benjamin believed that flesh-and-blood humanity lacks the ability to decide on justice, and can only hope to act as the faithful vessel for the justice of the Divine Will. But as Benjamin admitted, God’s Will is unclear and His justice is invisible — how are we supposed to know His desire? If “it is never Reason that decides on the justification of means and the justness of ends: fate-imposed violence decides on the former, and God on the latter,”33 then we can only figure out which ends are just and which are not through divine revelation, which is mediated by civil and religious authorities who use the threat of God’s unlimited wrath to shore up their own limited power. To preserve order, the Hand of God must be splayed before the void of senseless tragedies and the evil of self-interested destruction. Because divine violence is incomprehensible for humans, it is impossible for us to tell when we are being duped, to distinguish between genuine expressions of God’s Will and instances of mythic violence passing itself off as divine, like the violence in the legend of Korah. Pre-Marxist Benjamin recognized this problem, but his response, influenced by the long tradition of skepticism in Jewish epistemology and the pessimistic Early German Romantic theory of knowledge as approximation, was debilitating collective self-deprecation. In “Critique of Violence,” he conceded that divine violence can never be identified as such with any certainty, and in a short text written the year before the Bolshevik Revolution entitled “Notes to a Study of the Category of Justice,” Benjamin concluded that, because justice is a purely divine category, “there is no system of possession, regardless of its type, that leads to justice,” which explains why “every socialist or communist theory falls short of its goal”. As Lacan noted wryly in Seminar XX, “the subject bars himself more often than it is his turn to do so”. By denying transcendence to humanity and restricting it to God, whose Will is enigmatic and whose Voice is filtered through opportunistic ideologues, young Benjamin severely limited human access to justice and excluded the possibility of political justice. He believed we have an ethical obligation to “wrestle with” divine justice and divine violence and actively attempt to be faithful to the Divine Will, but at this point Benjamin lacked the materialist method which would make it possible for him to do anything more than wish us good luck.

Soon after writing his “Critique of Violence,” Benjamin engaged with the work of Karl Korsch and Georg Lukács, moved closer to communism through his relationship with Bolshevik revolutionary Asja Lācis, and became a full-blown Marxist around the time of his rejection by German academia in 1925. Years later, Benjamin told a friend that divine violence had been “an empty box, a limiting concept, a regulative idea,” one which he had replaced with a different, graspable, concrete idea: “class struggle”.34 The cure for pessimistic and impotent idealism is optimistic and empowering materialism, because of its ability to answer the otherwise-unanswerable question: «Что делать?». When Benjamin transposed ethics from the traditional realm of God into the secular realm of class struggle, he cleansed himself of theological impossibilism and exchanged divine violence for transcendent violence. By internalizing the transcendence of the Divine Kingdom, Benjamin pointed us toward the lesson of Julian Jaynes’ infamous “breakdown of the bicameral mind”— the Divine Will can be transferred to the will of the human subject. In a 1925 essay on the relationship between faith and action, Peruvian communist José Carlos Mariátegui wrote that “revolutionary excitement is a religious emotion. Religious motives have been displaced from the heavens to earth. They are not divine; they are human, social.”

Benjamin, like Badiou, never extended transcendence to the mere life of the human animal, but he did extend it to human subjectivity and the revolutionary struggle for human liberation. The transcendent violence of the revolutionary class struggle has all of the positive attributes of divine violence: it exceeds historical periods and national borders (“Enough republics! We’ve had enough of empires and nations… Europe, Asia, America: Disappear!” — Rimbaud), it attacks State power rather than reforming it, and it obliterates the old world so that a new one can be born. But it also has a distinct advantage over its religious predecessor: its justice is universally identifiable, because it is rooted in something we can access without the mediation of a self-interested authority figure, something with an objectively-certain existence — subjectivity. Violence that serves the liberation of subjectivity is transcendent, and violence that serves to oppress and destroy subjectivity is evil.