A Constellation of Reactions to History

Part 3 of 6

May 2021

Table of Contents

Betrayal

- Shabbetai Tzvi, False Messiah

- Leaving the CPUSA

Giving Ground

“The pledge we wore — I wear it still

But where is yours? — Ah! where are you?”

— Lord Byron, To Thyrza, 1811

“Who you loyal to?

Me or us?

Who you trust the most?

Me or us?”

— Young Thug, Me or Us, 2017

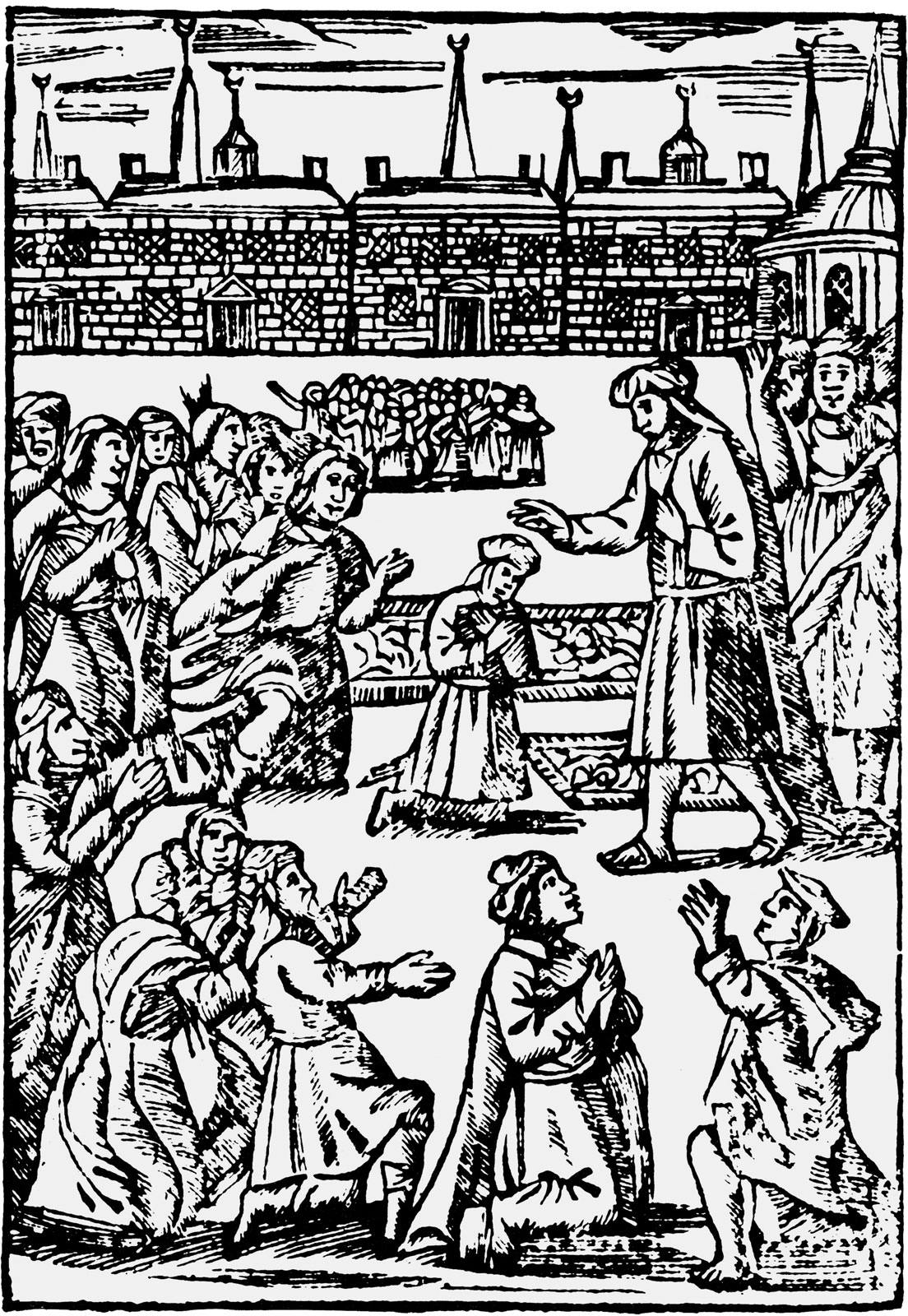

In 1668, a Jew who considered himself to be the prophet of the Messiah traveled to Rome to wage a holy war. Three years earlier, at the age of 22, Nathan of Gaza launched an absolutely enormous mass movement, a Cause that commanded the frenzied support of at least half of the entire global Jewish population. Now, even after many of his comrades had lost faith, Nathan was on an apocalyptic mission in “the land of thick darkness” [Italy] where he aimed to “tread upon the lion” and “trample upon the serpent” once and for all by striking directly at the helm of Gog and Magog — the Vatican. Where were his soldiers? He did not recruit any. What was his battleplan? Carrying out a series of mystical rituals in the belly of the Christian beast, culminating in a ferocious coup de grâce — the tossing of a scroll bearing a magical curse into the Tiber River. The spell was supposed to bring about the downfall of mighty Armilus a year after Nathan cast it, and yet Rome was still standing in 1669 (although the Pope did die that year). What went wrong?

Nathan, like the hundreds of thousands of other Jews between 1665 and 1667 who believed that Shabbetai Tzvi was the Messiah, had grown accustomed to this experience of baffling disappointment, but Nathan’s fidelity to the Event of Tzvi’s Arrival never wavered. Nathan believed he had been granted a prophetic illumination, a vision of God’s chariot [merkabah] which delivered a message with “the utmost clarity”: Shabbetai Tzvi would redeem the Jews. After convincing Tzvi to embrace his destiny, encouraging Tzvi to travel the land proclaiming his Arrival, and disseminating the good news throughout the Jewish world in his electrifying letters, Nathan would issue many secondary prophecies, all of which he would eventually be forced to retract or revise, but he never betrayed his fundamental conviction that Redemption was unfolding with Tzvi as its vessel.

Although Tzvi was described as a handsome and charismatic man, he was not the ideal would-be king — he suffered from extreme shifts in mood, his temperament was passive, and his brilliance was restricted to his imaginative capacity for disobeying Jewish norms and traditions. But whether he was up to the task or not, he was perceived as the incarnation of the two principles that comprise the promise of apocalyptic theology: liberation and vengeance. In explanations of the unprecedented size and intensity of the Sabbatian movement, most of the attention has been devoted to the popular appeal of the rebellious, nihilistic, and sexual dimensions of Tzvi’s ideology: he rose to prominence through his performance of transgressive “strange acts” [ma’asim zarim], ritualistic violations of Jewish law. Gershom Scholem’s classic essay on the ideology of the Sabbatian movement, “Redemption Through Sin” (1936), primarily frames Tzvi’s significance and influence in terms of the mystical power and erotic liberation of a “dialectical eruption of new forces in the midst of old concepts,” a re-consecration of barren Jewish life achieved through the libidinal forces which contemporary Jewish scholar Daniel Boyarin has mischievously described as “Jewissance”. There can be no question that the intoxicating interpenetration of carnality and spirituality in Sabbatian religious practice inflamed the inhibited and unlocked their faith through passion. But equal emphasis should be placed on another motivation which drew the Jews to their aspiring savior: the desire for revenge.

In the wake of the Khmelnytsky massacre of Ashkenazi Jews in 1648, the Jewish communities of the world sunk into collective despair, brutalized and traumatized once more by their Gentile superordinates. Although Scholem dispelled the notion that Sabbatianism was a straightforward response to that catastrophe in Poland, he concurred with the theory that Tzvi first came to believe that it was his mission to lead the Jews to Redemption when the 22-year-old scholar observed the shattering events of 1648 — the Zohar had suggested that it would be the year of the Messiah’s Arrival, and instead it was just another year in which thousands of Jews were viciously murdered. Tzvi told his people that they would be subjugated no longer, that he had the power to vanquish the demonic forces binding them to the abyss, and after 17 years of rejection and scorn, his message finally broke through and the Jews rejoiced. In his epistles, Nathan explicitly promised that the Cossacks whose hands were covered in Jewish blood would be slaughtered in an act of divine retribution. The wild rumors, letters, pamphlets, and news reports that autonomously circulated and fueled the rise of Sabbatianism were brimming with bloodthirsty fantasies of Jewish revenge against their oppressors. Sabbatian Jews, emboldened by a report that “great stones had fallen from heaven on the Gentiles’ houses of worship” and other reports that “churches and mosques were swallowed up overnight,”1 responded to mockery from their neighbors by informing them that “the fall of the Crescent and of all the royal crowns in Christendom” were imminent and that they would soon be made “slaves by the power of the Messiah”. It was said that Tzvi had assembled the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel into an unstoppable 300,000-man army, which had already conquered many small Muslim cities and killed all of their non-Jewish inhabitants by the time it arrived in Mecca, where the (imaginary) Israelite soldiers killed every single Gentile, reduced their holy city to ruins, and looted the tomb of Muhammad.2 All of the accumulated grief, pain, and envy of the Jewish people was projected onto the almost-blank figure of Shabbetai Tzvi, the man God had chosen to restore glory and nobility to His children by ruthlessly crushing their overlords. In his 2001 book Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s “On the Concept of History,” Brazilian Jew Michael Löwy contrasted Benjamin’s concept of the “hatred” inspired by memories of enslavement with Nietzsche’s concept of the ressentiment of the oppressed, the difference being that ressentiment is a response to historical domination driven by a passive, impotent, jealous thirst for vengeance, while Benjamin’s “hatred” is an active, practical, revolutionary reaction to past suffering. The rage which Shabbetai Tzvi gave voice to was pure ressentiment.

The popular images of Tzvi as some sort of General Sherman of Medieval Judaism were very much off the mark — his idea of apocalypse was remarkably bloodless. He was an eccentric rabbi, not a military leader. Scholem wrote that while Sabbatian “Messianic expectations were definitely ‘political’ in character... the means by which Redemption would be worked were supernatural”; the objectives were worldly but the strategy was mystical. The plan of the Sabbatian vanguard was to “come unarmed to war” against the Ottoman Empire (the Gentile power in charge of Jerusalem) because traditions taught that the Last War would not be fought with physical weapons but with psalms — the singing of hymns would be sufficient to defeat the Janissaries and the other armies of the world. Luckily, Tzvi had a wonderful singing voice.

There were probably thousands of Jews who would have been willing to fight for him — many were ready to quit their jobs, sell their property, and join his flock even though they had not been invited — but Tzvi saw no need for troops. He and his advisers had studied the sacred texts and determined that he would arrive in Constantinople “mounted on a celestial lion, his bridle a seven-headed serpent,” and all of the Gentile nations and kings would bow down at the terrible sight of the Messiah riding his lion, the ancient symbol of the Kingdom of Judah. The Sabbatian leaders set off to confront the Ishmaelites, but, for whatever reason, the lion failed to materialize. Tzvi was arrested and brought before Sultan Mehmed IV. The Jewish masses of Constantinople and Adrianople were extremely excited about this royal hearing — they were confident that this would be the moment when Tzvi seized the Sultan’s crown and initiated the final sequence of Redemption. The Sultan offered Tzvi a choice: 1) convert to Islam, 2) endure a slow and agonizing death by vertical impalement to become a martyr, or 3) produce a miracle and win the crown. The miracle in question: strip naked and be set as a mark for the Sultan’s archers; if the arrows bounced off his skin instead of killing him, the Sultan (a deeply religious man) said that he would accept Tzvi’s Messianic status and cede his power. But Tzvi never saw himself as a straightforward miracle worker. He knew that he was beholden to his cyclical illuminations; when he entered into ecstatic states, he acted on the strange impulses which he believed to be divine, but on the day of his trial, he was “bereft of light,” which he took as a sign that God would not help him if he attempted to produce a miracle. Martyrdom, particularly in the form of a spintrian experience that even the Marquis de Sade would balk at, did not appeal to Tzvi. So he agreed to convert. The Jewish Messiah, the conqueror of the Gentiles, became a Muslim. Had the choice been offered to him slightly earlier, while he was still in a state of mystical euphoria and spirit, perhaps he would have chosen differently. Or perhaps he had simply realized that he was in over his head.

This turn of events was not what the Sabbatians had been expecting, to say the least. As the news leaked out, believers reacted to the shock of the Messiah’s apostasy in different ways. Many Jews immediately renounced their faith in Tzvi. Some of the defectors decided that his heretical Messianic movement had been fraudulent from the beginning, while others justified their former faith by arguing that “in the beginning there was in him the power of holiness, but later the evil powers fastened themselves to him and the devil’s work succeeded” (the revolution betrayed, the transformative forces degenerated under the influence of the klippot). But there were also many Sabbatians who did not allow this seeming betrayal to sway their faith. They had not anticipated this development, but the Messiah had never arrived before — all of the theories and writings up until this point had been mere speculation, incapable of fully predicting the path Redemption would take in actual practice. If they were patient, giving the movement’s leaders time to work through the contradictions and explain what was happening, surely all would become clear.

In the meantime, Muslims and Christians reveled in this scandal, ridiculing the hubris and idiocy of the gullible Jews. According to contemporaneous newspaper reports uncovered by Jetteke van Wijk, many Christians were optimistic “that now the Jewish Nation will open their eyes and recognize their true Messiah, and become Christian”. The rabbinical authorities, whose administrative and moral legitimacy had been annulled by Tzvi’s ascension, took this opportunity to reclaim their power from the Sabbatian masses, driving the remnants of the movement underground, prohibiting them from holding meetings or public demonstrations, and burning the books written by their theorists. Nathan of Gaza became a fugitive, banned from Jewish communities throughout the Mediterranean. His enemies began calling him “Satan of Gaza”.

Sabbatianism was not dead yet, however, and those who kept the faith demanded answers. The initial impulse of some of the leaders was to lie: they falsely asserted that the Sultan threatened to massacre the Turkish Jews unless Tzvi converted, a narrative which spun his apostasy as a noble sacrifice for the good of his people. Nathan’s guide for the perplexed echoed that general interpretation of Tzvi’s conversion as a heroic and selfless act, but his justification took a much more interesting and thoughtful route: Redemption could not be completed until the Messiah personally descended into the abyss, elevated the sparks that had fallen into the lower worlds, and destroyed the Empire of Darkness from within. This made Tzvi’s captivity within the heart of the Ottoman Empire similar to Samson’s captivity in the Philistines’ temple, except that Tzvi would be freeing the individuals unfortunate enough to be born into Islam rather than destroying them along with their evil world. According to Nathan, Tzvi’s mission was to become the “king of demons,” courageously infiltrating the realm of evil in order to reintegrate it into the realm of holiness by breaking the shell from within and liberating the lights trapped inside. He could not save the Gentiles [a new goal] without becoming a member of the Gentile world.

The dizzying twists and turns in the thinking of the Sabbatian movement can be traced through the writings of one of Tzvi’s young followers, Israel Hazzan. Hazzan’s initial attitude toward Islam was standard ressentiment, and his Messianic hopes were “merely a vain detour with the aim of catching the jouissance of the Other,” as Lacan wrote in Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (1963-1964). In Ezekiel 23:20, a Bible passage which has become a popular meme, a regrettable extended metaphor comparing the Kingdom of Judah to a promiscuous young woman comes to a head: “she lusted after lovers with genitals as large as a donkey’s and emissions like those of a horse”. Hazzan directly compared medieval Muslims to those well-endowed and virile Ancient Egyptian lovers from Ezekiel who kept all of the pleasure and power to themselves, satisfying their voracious appetites by “devouring the Jews with every mouth”.3 Even as Hazzan used gematria to correlate their “meshugga” prophet Muhammad with the “large lizards” designated as unclean by kashrut, he admitted that Muslims “bear no yoke” and “have not gone into exile,” giving these “neighbors who are our enemies” the ability to “mock and ridicule us”. The Jews were subservient cuckolds for the time being, but Hazzan had faith in Tzvi’s supposed plan: attaining victory through deceit, just as Jacob gained Isaac’s blessing by disguising himself as Esau. This detour within Islam, that “twisted” and “vain” “path of fools and lunatics,” would pay off once Tzvi reversed the roles, “riding and dominating the ass of Ishmael [Islam] and the ox of Esau [Christianity],” turning the Gentiles into the submissive servants of the Jews. Abraham Cardoso, one of the Sabbatian movement’s most influential leaders, invoked sexual mystical imagery from the Zohar in order to arouse the attention of the Jews to the bursting potency of the “crowned divine phallus of the Messiah” (in the treatise in question, Cardoso actually positions himself as the penetrative element “pouring out” into the penetrated Tzvi to infuse him with the “shine” that Tzvi lacked on his own, a framing which is neither here nor there, although there were unconfirmed-but-plausible contemporaneous rumors of the Messiah engaging in bisexual rituals with his followers). The pivot to universalism which Nathan had signaled was interpreted by Hazzan (and other Sabbatians for whom “Messianism” merely meant “the seizure of power”) as nothing but a trick concealing Tzvi’s explosive strength, a disguise masking his true intentions, because Tzvi remained “like the body of the Heaven in his purity” in spite of the impure turban on his head. The only problem with this theory was that Tzvi did not have “true” intentions in any meaningful sense — his statements, writings, and letters reveal that his personal understanding of his goals and strategies was just as divided, tortured, and volatile as the collective understanding of his followers.

Years went by and nothing changed. Nathan consistently pumped out vague, grandiose announcements about imminent divine interventions, and with each non-Event, larger and larger chunks of the Sabbatian movement fell away. The rank-and-file became disillusioned with the leaders’ constant conflicting fluctuations between the three positions which Tzvi sincerely held to varying degrees, depending on the day, the crowd, and the mood he was in: the “public” Muslim particularism which convinced small groups of Sabbatian Jews to convert to Islam and aimed at reassuring the Sultan that Tzvi was a genuine and faithful convert to Islam; the “theoretical” universalism which aimed at reading beauty, love, and hope into the act of apostasy; and the “undercover” Jewish particularism which secretly convinced a handful of Muslims to convert to Sabbatian Judaism and aimed at covertly reassuring the Jewish masses that they had not been betrayed and that their revenge against the Gentiles was still on track.

The rabbis of Constantinople were not content with allowing Sabbatianism to disintegrate through a gradual process of disenchantment; they desperately wanted to put a nail in the destabilizing movement’s coffin. But Tzvi enjoyed the favor of the Sultan, so Turkey’s Jewish leaders cooked up a conspiracy against the dangerous renegade, devising an intricate plot involving bribes and informants to convince the Sultan that Tzvi had been deceiving him (which was true, to some extent). The Turkish Jewish Establishment sought Tzvi’s execution, but they had to settle for his exile — apparently the Sultan’s mother had grown fond of Tzvi.

The worst was yet to come for the Sabbatians: after a few years of diligently continuing the mystical work of Redemption in isolation with his loyalists, the Messiah died of a bowel obstruction. All of his disciples were quite confused by this, and they kept it a secret as long as they could. They decided that it was only a temporary measure, an “occultation” rather than a true death, and they felt certain that he would return shortly.

While he waited for Tzvi to re-appear, Israel Hazzan’s position on the Muslim Question softened. Now he wrote that “the Turkish king” — whom he described earlier as a filthy rat — “will have a high rank with the Messiah even after his second coming,” and “it appears that the Muslims [as a whole] will have some measure of rank with the Messiah,”4 as Tzvi “is going to exalt the Muslims’ power even after the [second coming], in accord with that which the Lord of the World wishes to grant them”.5 Hazzan implicitly conceded that though his previous goal had been to annihilate Islam, he finally understood that the destruction of the Muslims would “blemish” the Jews, as we are siblings who must try to mend each other instead of struggling to dominate or destroy each other.6 In Hazzan’s account, Tzvi, like Abraham before him, initially intended to kill one of his sons, but through his apostasy, he came to realize that Redemption did not require filicide on his part or fratricide on the part of the Jews, and that the only slaughter to be carried out was that of the ram, which was taken by Hazzan to represent the genocidal Cossacks, the only Gentiles whose destruction he continued to endorse. As a reward for Tzvi’s gracious descent into the hostile domain of Islam, Hazzan believed that God would grant “two blessings: one for the Jews and one for the Muslims. And in multiplying God will multiply — two times — thy seed, whichever seed of yours it may happen to be, both of them being equally good... All the rest of the nations, the Cossacks excepted, shall be mended on account of Tzvi and his acts of mending… and the Jews, Christians, and Muslims will rise up and go together, all of them as one, to Beersheba.”7

This touching egalitarian vision of near-universal transcendence was not to last, however. As Tzvi’s period of “hiding” persisted and Hazzan’s hope faded, he returned to bitterness and envy. Our “equally good brother” was back to being described as a “vile nation”. “Jealousy is cruel as the grave,” Hazzan lamented. “This is the jealousy which we feel because the light and holiness of Israel has had to enter this trial. It is a very cruel jealousy.” Hazzan begged God to show His mercy by launching an attack on the Muslims as retribution for dragging the Sabbatians down into the realm of darkness and profanity.8 Hazzan felt betrayed — by his fellow Jews (through their defections, condemnations, and excommunications), by Tzvi (through his death), and by God (through His decision to allow the Muslims to triumph over the Jewish people and the Sabbatian movement). Hazzan lapsed into despair; the Sabbatian struggle to mend the world had failed. Tzvi’s inability to transform social relations is the only evidence we have and need to describe him as a “false” Messiah.

When he was in power, Barack Obama liked to justify his gradualist approach to improving the American Empire by appealing to a quote he attributed to Martin Luther King, Jr.: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice”. When examined in context, however, it becomes clear that Reverend King was using the quote not to express his political optimism regarding the fate of the fallen world but his Christian faith in the inevitability of the next world.9 Though evil reigns in the City of Man, the arc of the universe bends toward the Return of Christ, the Last Judgment, and the Day of Resurrection. Once Israel Hazzan lost all of his faith in the power of Sabbatianism to redeem the City of Man, he adjusted his forecast for the arc of the universe: Shabbetai Tzvi would not return “soon” but on the world’s Final Day, “at the crushing of the soul, at the end of all souls, when all humans return to their dust and the earth returns to be renewed”.10 Hazzan wrote that “all of our hope must be for those future days, when the Lord will make wings for us and we will fly” — life on Earth is beyond repair, but dejected believers like Hazzan can take comfort in a “wistful fantasy of a world to come [olam ha-ba] in which dreams come true and pains are healed”.11

/

/

/

After reading an essay he was not supposed to read, James Cannon decided to become a traitor. Cannon was a co-founder and leader of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), but his infidelity following an awakening at the Sixth World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern) in Moscow in the summer of 1928 led to a messy divorce. The document which precipitated Cannon’s treachery was written by L**n T*****y, who had just been beaten in his factional struggle against Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Bukharin, kicked out of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and banished to a remote town in Central Asia. Apparently the text fell into Cannon’s lap through a pencil-pusher mishap; the story goes that the Soviet bureaucrats messed up, mistakenly translating and distributing a critique of the Comintern written by Judas himself. Cannon already had private, embryonic misgivings about the direction Communism had taken since the defeat of the Hamburg Uprising in October 1923 and the death of Vladimir Lenin in January 1924, and now a heretical document (translated into English as “The Third International After Lenin”) had been delivered to him, developing and expressing all of his concerns in the clearest of terms: Trotsky explained and attacked the rapid and unprincipled “zigzags” in Comintern policy, Stalin’s Russian-nationalist doctrine of “socialism in one country,” the Comintern’s advocacy for critical support of agrarian-populist Western politicians like Senator Bob La Follette, and Stalin’s support for the reactionary Guomindang (Nationalist Party) in China. Cannon’s vague doubts solidified into certainty that the revolution had been betrayed by the Party’s new leaders, and that “Trotsky and the [Left] Opposition represented the true program of the revolution — the original Marxist program. What else could I do but support them? And what difference did it make that they were a small minority, defeated, expelled, and exiled? It was a question of principle.”12 Cannon later wrote that Trotsky’s essay forced him to realize that “the footloose Wobbly rebel that I used to be had imperceptibly begun to fit comfortably into a swivel chair… I saw myself for the first time as another person, as a revolutionist who was on the road to becoming a bureaucrat. The image was hideous, and I turned away from it in disgust... I never deceived myself for a moment about the most probable consequence of my decision to support Trotsky… I knew it was going to cost me my head and also my swivel chair, but thought: What the hell — better men than I have risked their heads and their swivel chairs for truth and justice.”13 He snuck Trotsky’s essay back to the United States and went about luring as many other Party leaders and organizers to the dark side as possible before his inevitable expulsion was handed down by the factions led by his rivals, William Foster and Jay Lovestone (the latter apparatchik would soon undergo the same humiliating purge-collaborator-to-purge-victim turn of fortune as his friend Bukharin).

The most notable Communist to follow Cannon out of the Party and into Trotskyism was Max Shachtman. He was born into the milieu of radical immigrant politics in turn of the century New York City — Shachtman’s father was a Jewish immigrant, a union member, and a socialist, and Shachtman grew up in multi-ethnic proletarian neighborhoods (the Lower East Side and Harlem) bursting with the rebellious energy of organized, class-conscious, socially-oppressed workers. He entered revolutionary politics as a sharp, funny, and articulate teenager and quickly became a leader in the Communist youth movement. His likability, his leadership skills, and his talent as a reporter, writer, and journal editor turned him into a rising star in the Party. But when his mentor shared Trotsky’s revelations with him, the effect was “absolutely shattering,”14 and — in contrast to other Cannon allies like Charles Shipman and William Dunne who turned their backs on their close friend — the 25-year-old Shachtman did not hesitate to pledge his loyalty to Cannon’s new Cause and sacrifice his promising career within the “Stalinist” Communist Party. Did this make him a courageous and principled young man [a mensch, even?] or a fallen angel, tempted into a life of sin by the fruit of cursed knowledge offered to him by the serpent Jim Cannon? If it makes any difference, Cannon’s former friends who rejected his blasphemous message did not end up as Party “lifers,” either — Charles Shipman was expelled a few years later because of his burgeoning anti-Stalinism and became a prosperous businessman after the war, while Bill Dunne was expelled for ultra-leftist “attacks on the Party” in 1946 and led an external struggle against the CPUSA’s “revisionist” deviations from genuine Leninism for the remainder of his life.

In the months following their expulsion, Cannon, Shachtman, and about 100 other defectors launched the “Communist League of America (Opposition)” with financial support from quasi-Trot iconoclast Max Eastman and a group of Italian immigrants aligned with Amadeo Bordiga’s left-communism. The Communist Party tried to violently suppress this league of back-stabbers, forcefully disrupting their meetings and even going so far as to burglarize Cannon’s apartment, but Cannon reached out to some old Wobbly buddies and put together a “Workers Defense Guard” to protect the small movement that he hoped would form the nucleus of a redeemed Party. His Trotskyists won a few impressive and consequential labor struggles during the 1930s, and they also successfully nurtured the growth of Trotskyist movements abroad in countries like Argentina, but they failed to sufficiently grow their ranks, remained mostly isolated from the masses, and could not compete with the surging New Deal Democrats or the Communist Party, which was peaking in spite of its massive membership-turnover rates. Cannon, who dropped out of school to join the workforce when he was 12, had little in common with his brainy band of rebels; the American Trotskyists of the Great Depression Era were disproportionately (though not exclusively) well-educated middle-class intellectuals with weak or non-existent organic ties to the industrial labor movement that birthed their leader. This problem was exacerbated when his Communist League merged with the American Workers Party, a small independent socialist organization led by radical intellectuals like New School professor Sidney Hook and NYU professor James Burnham. The Trotskyists’ abortive attempts to bridge the divide that separated them from the masses generated bitter and destabilizing strategic disagreements and factional tensions.

In the late 1930s, American communists of all affiliations experienced a Soviet one-two punch — the Great Purge of 1936-1938 and the Stalin-Hitler pact of 1939 — that sparked a wave of apostasies which would reverberate through American politics for generations. The purge was a violent “cleansing” [чистка] program carried out by Stalin’s administrative machinery to reinforce its monopoly on political authority, to preserve its ruthless system of accumulation, and to protect the national security of the Motherland from any disloyal threats to its ability to defend itself against Germany and Japan. In Alain Badiou’s typology, the Great Purge is the form of Evil called “the disaster” — the disastrous consequences of the “absolutization of the power of a Truth,” the USSR’s overestimation of its ability to “force the naming of the unnameable,” its unwillingness to admit to the limits of its access to Truth. What makes their deranged crusade for “total power” count as evil in Badiou’s eyes is its “interruption” of the revolutionary “Truth-Process” — their hunt for traitors was an act of treason against the Cause, their attempt to stabilize the State served to destabilize the revolutionary forces. But while Badiou’s discussion of the purge only mentions the “elimination of human-animals” in passing, many international communists granted far more ethical weight to its effects on “mere life”. Over the course of three years, millions of people were incarcerated and hundreds of thousands of people were killed by the sprawling, unfeeling limbs of the Soviet government. Expelling traitors from the Party was no longer considered a sufficient method of maintaining political stability; the heroes of the Bolshevik Revolution were arrested and tortured by the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD), charged under the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic Penal Code, prosecuted by the Procurator General of the USSR, found guilty of treason by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR, and executed by the Main Directorate of State Security. After Stalin’s administration had wiped out all of its remaining rivals and critics, Stalin and his foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, made a series of deals with the Nazi government. Stalin and Hitler agreed to divvy up Poland, give the Soviet Union the right to annex Finland, and provide each other with critical resources and military supplies. The duo immediately went about conquering their allotted regions of Poland, and within a few months the Soviet rulers also embarked on a disastrous invasion of Finland, killing at least 50,000 Soviet soldiers and 25,000 Finnish soldiers in the process. The Nazis went on to massacre 3 million Polish Jews (90% of Poland’s Jewish population) and 2.7 million non-Jewish Poles. The Red Army invasion of Poland led to the deaths of thousands of soldiers on both sides, and once the Soviet network of occupation internment camps was fully operational, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU ordered the NKVD to execute tens of thousands of Polish prisoners of war.

The extreme disregard for human life demonstrated by the Soviet State and the absurd trials of the revered Old Bolsheviks had already placed a tremendous strain on the faith of many American Communists, and so the Soviet leadership’s willingness to enter into a “friendship treaty” with a genocidal fascist regime for the purpose of expanding the territory of the USSR through wars of aggression became the straw that broke the camel’s back for thousands of American Party members, particularly the Jewish and Black radicals who joined the CPUSA because they saw Communism as the only trustworthy bulwark against the forces of oppression that threatened them. The USSR was supposed to serve as the first power-holding champion of the international proletariat, and instead it was revealed to be more of the same, another self-interested, rapacious, amoral nation-state. Stalin’s national anthem reform provided some on-the-nose symbolism: he replaced The Internationale with a new patriotic ode to mighty, glorious Великая Русь. The empowerment (and lives) of the masses and the transformation of social relations had been subordinated to the geopolitical objectives of the productivist bureaucrats of Great Russia. The violence they unleashed was not transcendent — it was just evil. It would be impossible to calculate the amount of talent and energy that the revolutionary movement in the United States was deprived of as a result of the demobilizing despair induced by this realization at the end of the 1930s. For countless American radicals, the aura of the USSR had been punctured, and the reckless American cathexis of this political entity and its leaders with Messianic expectations guaranteed that their revolutionary hopes would evaporate as soon as the Soviet spell had been broken.

The events of 1936-1939 also caused dozens of prominent American radicals to become — for lack of a better word — twisted. One of them was Whittaker Chambers, a writer who joined the Communist Party because “it offered me what nothing else in the dying world had the power to offer at the same intensity — faith and a vision, something for which to live and something for which to die”. For years, Chambers served his Cause devotedly as a spy for the Soviet Union. But reports of the Great Purge horrified him, the paranoid NKVD killings of several of his fellow spies outraged him, and he had reason to worry that Stalin was planning to thank him for his service by having him executed too, so he left the Party and went underground to hide from Stalin’s assassins. After the Soviet-German treaty was announced, Chambers decided that he needed to stand up against “Communazi” totalitarianism, so he snitched on his Red friends, filled the void left behind by Communism with Christian fundamentalism, strove to defend the greatness of Western Civilization, went to work as a Senior Editor for William Buckley’s National Review, and profited off of his apostasy by writing a best-selling memoir confessing to his anti-American sins and begging for forgiveness. Bertram Wolfe was another loyal Communist turned Cold Warrior; Wolfe was a co-founder of the CPUSA and one of the Party’s most effective speakers and recruiters until he was expelled by Stalin and Foster along with Jay Lovestone in 1929 because of their ties to Bukharin [“a faster case of ‘biters bit’ is not on recent record” — Shachtman]. Wolfe remained a radical activist and a labor organizer, but the Moscow Trials led him to speak out against the Soviet Union, and he left revolutionary politics behind to become a committed anti-Communist after the Stalin-Hitler pact. He eventually got a job as an imperial propagandist with the US State Department and ended his career as a Senior Fellow at a conservative think tank. After Stalin had Bukharin shot and the CPUSA had Lovestone’s apartment burglarized (something Lovestone had done to Cannon a decade earlier), Wolfe’s mentor removed the word “Communist” from the name of his “loyal opposition” group and went to work for the CIA. Like Wolfe, Max Eastman had been one of America’s most popular spokesmen for revolutionary politics during the 1910s-1930s, but the Great Purge (in which his brother-in-law was executed) was the moment of The Fall for him. The indiscriminate State violence persuaded Eastman that socialism had “ended” in the USSR and been replaced by a totalitarian system indistinguishable from fascism. Then the Stalin-Hitler deal demoralized him so severely that he became convinced that socialism had always been doomed to degenerate because human nature is inherently flawed, rendering collective transcendence impossible. Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom (1944) taught Eastman that free-market capitalism was the only social form capable of protecting individual freedom from collectivist tyrants like Stalin. He spent the rest of his life speaking out against Communism, writing articles in support of McCarthyism, and contributing to National Review.

It would be reasonable to assume that a crisis of faith which led thousands of American Communists to disavow Stalin would serve as an invigorating boost for the American Trotskyists, but the Soviet-Nazi pact only inflamed the contradictions within their movement and embroiled them in factional infighting that resulted in the fragmentation of their unstable coalition. In 1940, their Socialist Workers Party split roughly in half between the opposing blocs led by Cannon’s clique, which skewed toward “vulgar practicalist” Midwestern trade-unionists who were completely disinterested in “theory,” and Shachtman’s clique, which skewed toward “haughty” “dilettantish” New York intellectuals who were obsessed with theoretical minutiae. Around 55% of the Trotskyists stuck with Cannon’s rigid, “sterile,” “self-preserving,” “bureaucratic conservative” tendency, and around 45% (including radical scholar Hal Draper and most of the party’s youth wing) ignored Trotsky’s endorsement of Cannon and sided with the revisionist, “unstable,” “irresponsible,” “petty-bourgeois” tendency of Shachtman and James Burnham. Cannon’s position on the fatal “Russian Question” — a position he took straight from “The Old Man” Trotsky himself — was complicated: although he refused to support the United States in its war against the Axis, it was still necessary to unconditionally defend the Soviet Union. Its actions over the last few years had been indefensible, but the USSR’s State-owned property and planned economy needed to be protected from the capitalist powers, and the Trotskyists were also optimistic that Stalin’s “Bonapartist dictatorship” would soon be overthrown by a new proletarian revolution which would regenerate the USSR, and that would be impossible if the Soviets lost the war.15 Shachtman’s opposing position underwent several amendments throughout the war, and at times it seemed to differ from Cannon’s Orthodox Trotskyist stance only in tone and terminology, but it was founded on a sentiment that would remain consistent for the rest of Shachtman’s life: a vehement and unwavering repudiation of the Soviet Union. The CPUSA, for its part, patriotically supported the incarceration of Cannon and other members of the disloyal “Trotskyite Fifth Column” who deserved to be “exterminated... from the life of our Nation” on the basis of their refusal to “suspend the class struggle” in order to aid President Roosevelt’s war effort; they also supported Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese Americans, including some of their own Party members, as a “necessary war measure”.

The hostility of Trotskyist academic James Burnham felt toward the USSR became so all-consuming that he quit the new Shachtmanite splinter group after only a month to become an anti-Communist ideologue alongside his Trotsky-sympathizing intellectual mentor, Sidney Hook. Burnham co-founded National Review and Hook became a neoconservative. Shachtman was still a Trotskyist, however, and he recruited many young and bright radicals to his Cause, including Irving Kristol and Irving Howe, both students at the City College of New York. Along with a few other Shachtmanites, Howe would go on to found Dissent magazine, a leftist publication dedicated to “defending democratic, humanist, and radical values” from both Stalinism and McCarthyism. Dissent’s middle way was inspired by Burnham’s discarded “Third Camp” theory of internationalism, which held that socialists should remain rigorously independent instead of giving their loyalty to either the imperialist West (“Washington”) or to the expansionist Stalinists (“Moscow”).

Both Cannon’s party and Shachtman’s party were actually fairly successful in their respective propaganda campaigns, labor struggles, and recruitment drives between 1940-1947, but then several factors combined to halt Trot momentum and begin the movement’s disintegration into a pitiful assemblage of irrelevant, cultish sects. Chief among them: postwar American prosperity had a powerful de-radicalizing effect on those who benefited from it (which was not everyone). Other impediments: attempts to re-unify the heterogeneous American Trotskyist world failed, and the beginning of the Second Red Scare under President Truman in the wake of the 1945-1946 strike wave made revolutionary organizing far more difficult. The TKO: the Shachtmanites’ intensifying desire to distance themselves from Stalinist “totalitarian bureaucratic collectivism” caused them to break away from Leninism altogether in 1949, re-branding as the “Independent Socialist League”. Shachtman’s principled “Third Campism” and his “democratic” vision of socialism did win him another important young disciple, however: Michael Harrington.

While Shachtman was gradually drifting away from his Communist origins, other radicals gleefully leapt into the open arms of the postwar status quo. Formerly-marginalized European immigrants were being welcomed into the fold of American whiteness, and many of them sacrificed their militant politics to embrace the new opportunity to live comfortable and stable lives under the Fordist-imperialist regime. Irving Kristol abandoned Shachtmanism to become the godfather of neoconservatism at Commentary Magazine along with Norman Podhoretz, a former leftist himself. The two men were united in their careerism, their anti-Stalinism, their Zionism, their racism, their patriotic cheerleading for imperialist wars, and their anti-utopian religiosity. By the 1980s, Kristol and Podhoretz were attacking Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush for being too soft on Communism. Their sons, Bill Kristol and John Podhoretz, also became prominent neoconservative commentators, bonded through their fathers’ partnership and their shared history of embarrassing themselves on Twitter.

Will Herberg was another pre-war radical Jew who became a postwar reactionary after deciding that faith in the ability of humans to mend the world through politics was an arrogant secular delusion. Herberg got his start as a Lovestonite and remained active in the labor movement long after his faction was pushed out of the CPUSA, but he gave up on political organizing in 1948 when he came to the same conclusion as anti-Communist Christian theologian Reinhold Neibuhr: “history cannot be coerced”.16 Herberg’s anti-Stalinism encouraged him to believe that “utopianism leads to tyranny,” which means that our hope for Redemption must come from faith in God, the only being who possesses genuinely transformative power. Herberg struggled against idolatrous subversives in the pages of National Review by encouraging the American government to suppress the tendencies of the foolish populace toward disorder and mob rule. Louis Budenz also replaced lacking Communism with lack-less God, although his God was trinitarian. Budenz started out as a gritty labor organizer who had been arrested for his radical union activity 21 times, and he then served as the managing editor of the CPUSA’s Daily Worker and as a member of the CPUSA’s National Committee. But when a celebrity priest showed him the light (along with Bella Dodd and other Catholic radicals), explaining that the Blessed Virgin would not approve of Communism, Budenz renounced revolutionary politics and was rewarded with several book deals and a $70,000 agreement with J. Edgar Hoover to inform on his comrades to the FBI.

The Communists who remained true to their Cause after the war were subjected to judicial repression (with the help of traitors like Budenz and Chambers), expulsion from the labor movement by liberal union bureaucrats (with the help of traitors like Lovestone), and ubiquitous anti-Communist propaganda in the media (with the help of traitors like Wolfe, Eastman, and Kristol). This pressure — along with other push and pull factors, like a few self-destructive purges and the siren song of social democratic wealth funded by neo-colonial extraction and the super-exploitation of the mostly-Black underclass — took its toll on the CPUSA. After hitting a postwar peak of 75,000 members in 1947, Party enrollment plummeted down to 38,000 by 1950 and 20,000 by the end of 1955. The stagnation and rigidity of the leadership’s analytic methods and the mechanical and outdated nature of their understanding of the new political-economic reality in the United States made it impossible for them to adequately adjust their strategies to adapt to their movement’s changing situation. As the mainstream unions systematically purged anti-capitalists from their ranks, CPUSA leaders stubbornly urged “labor unity” and refused to support efforts by militant labor organizers to launch a new radical labor federation capable of challenging the hegemony of the anti-Communist AFL and CIO. Faced with the beginning of the Golden Age of American capitalism but armed only with half-grasped concepts derived from revolutionary instruction manuals, they confidently proclaimed the imminence of the total collapse of the capitalist economy in a depression that would “dwarf the economic catastrophe of 1929-1933”. Their stupidity was an inevitable byproduct of the Party’s decades-long policy of culling members who exercised unorthodox and innovative subjectivity. It was much easier for the Party to serve as the passive, unthinking instruments of infallible Soviet leaders and to rely entirely on the dictates of authoritative Soviet rulebooks than for the Party’s leaders to do the uncertain and painful work of thinking about their problems on their own (especially when Soviet funding was contingent on obedience). As they would soon learn, mindless faith turns unexpected developments into devastating setbacks.

The shock-effects set off by Nikita Khrushchev in 1956 triggered a collapse within the brittle CPUSA from which the Party would never recover. At the end of the 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956, three years after the death of Stalin, Khrushchev convened a closed session of Communist Party delegates to inform them that they had been betrayed. In a four-hour speech, Khrushchev revealed that Stalin had deviated from “the spirit of Marxism-Leninism,” “eliminated the possibility of any kind of ideological fight or the making of one’s views known,” “abused his power,” executed 70% of the Party’s Central Committee members, tortured alleged spies and saboteurs into making false confessions, failed to properly prepare for World War II, treated Soviet workers as if they were his enemies, fabricated several conspiracies, “completely lost consciousness of reality,” and forced Communists to glorify, flatter, and adore him. Not to worry, though — Khrushchev promised to “restore completely the Leninist principles of Soviet socialist democracy” and “revolutionary socialist legality”. René Girard posited that communities overcome internal rivalries and conflicts by uniting themselves against a scapegoat that they simultaneously internalize and externalize, treating this cursed individual as both poison and cure; in Khrushchev’s telling, Stalin acted as an isolated internal threat to the integrity of Marxism-Leninism during his lifetime, but could become the instrument of the regeneration of the Soviet Union after his death, so long as the Soviets successfully murdered his “cult of personality”. Khrushchev’s secret speech ultimately succeeded in stabilizing his domestic political situation and shoring up his personal control over the post-Stalin CPSU, but his exposure of Papa Joe’s lack crushed the spirit of thousands of diehard American Communists. After the speech was read out at a CPUSA National Committee meeting two months later, the delegates were stunned that the Messianic incarnation of their Cause had been responsible for this interminable list of atrocities; a few sobbed. Steve Nelson, a distinguished veteran of the Spanish Civil War and a widely-respected leader within the organization, “felt betrayed” as he “looked into the faces of people who had been beaten up or jailed with me” and “broke the deafening silence,” telling them: “this was not why I joined the Party”.17

But when other outraged members asked Nelson to become the leader of a Party reform movement and challenge the unmoved Old Guard led by Bill Foster, Nelson declined. He felt that the Chairman of the CPUSA “should be a native-born citizen” (he was born “Stjepan Mesaros” in a tiny Croatian village), and he also did not see himself as “an outstanding writer” or a “strong speaker” (when he immigrated to Philadelphia at the age of 17, he was barely literate in Serbo-Croatian; he learned to read English through radical pamphlets and classic Marxist texts).18 Eugene Dennis was another long-time leader in the Party who was well-positioned to lead a reform coalition after writing his “New Look” report, a bold, unflinching internal critique of the Party’s postwar dogmatism. But even though he spoke out against Stalin’s “left-sectarianism,” Khrushchev’s speech had not caused Dennis to waver in his loyalty to the Soviet Union, and he prioritized the stability and internal cohesion of his Party over its real-world efficacy. The organizational interests of the CPUSA and the CPSU were considered to be identical with the interests of the masses, which conveniently eliminated the necessity of making any serious (and inevitably divisive) effort to tether the Party line to the subjectivity of the masses. The Party thinks, the people act. Thus the perspectives and complaints of on-the-ground local Party organizers were ignored by out-of-touch National higher-ups in their swivel chairs — yet another missed opportunity to react to historical disillusionment in a productive manner. There were intelligent and competent female organizers such as Louise Todd and Oleta O’Connor Yates who became vocal advocates for transforming the shape and direction of the declining Communist movement in the 1950s, but, as Nelson would later write, “women seldom advanced to the top leadership posts”. Benjamin J. Davis, Jr. — the highest-ranking Black member of the CPUSA and Harlem’s City Councilman — was deeply shaken by Khrushchev’s speech, but sooner or later he regained his composure and acted as one of the most uncompromising and ferocious opponents of Party reform. Would Badiou congratulate Davis for successfully avoiding one of his three forms of Evil: “the renunciation of a difficult fidelity”? Was Nathan of Gaza right to refuse to renounce Sabbatianism? Or should these stubborn men have followed Sophia Papadopoulou’s injunction to “devalue the crown that had supported their desire for so long,” lest they remain “victims of an illusion”?

John Gates was different from the rest of the Party leaders. Like Nelson, he was a long-time organizer and Spanish Civil War veteran who was shocked and horrified by the revelations about Stalin, but the ambitious Gates had no problem putting himself forward as the best individual to lead the effort to “radically transform the Party from within”. He was the Editor-in-Chief of the Daily Worker, and he made full use of the leverage this position granted him: his paper was the only Communist Party organ in the world to print the secret speech, and he took the unprecedented step of soliciting letters from the paper’s rank-and-file readers and publishing all of the responses, regardless of their viewpoints. Gates and his democratizer faction came to believe that Leninist organizational principles were the underlying cause or enabler of Stalin’s despotism, calling into question the validity of democratic centralism and the vanguard party model. This was too far for the majority of the remaining Party members, for whom Orthodox Leninism was the only legitimate form of communist politics; to drastically revise the organization’s structure and logic (“liquidationism”) would be tantamount to ceasing to exist as communists.

Once Khrushchev sent tanks into Hungary in October 1956 to suppress uprisings against the Soviet puppet government and destroy the Prime Minister who announced that Hungary would be leaving the Soviet Bloc’s Warsaw Pact, there was no longer any hope of building unity between the CPUSA’s divided reformers. The Party imploded. The post-secret-speech factional struggles would finally end a year later with the vast majority of the remaining reformers giving up on the Party or getting forced out of it by the conservative Foster faction, but even before the mass defection of the defeated activists in late 1957-early 1958, thousands and thousands of American Communists flooded out of the Party as the USSR put down the rebellion in Hungary by killing at least 2,500 Hungarians (including their reformist Prime Minister, Imre Nagy) and arresting 26,000 of them. When Foster was confronted about his role in accelerating this exodus by a concerned CPUSA loyalist, he replied: “Let them go, who cares? Even if the Party goes down to only 50 members, if they are true Marxist-Leninists, staunch people, it doesn’t matter. It is better to have 50 true members than 50,000 who are not genuine Communists.”19 If they failed their “crisis of fidelity” and refused to obey Badiou’s ethical maxim to “Keep going,” who needed them? Foster was disgusted by the disillusioned members’ “gross exaggeration of errors” and thought it was ridiculous and self-destructive for the Party to “lambast itself so mercilessly,” so he shut down the (already-bankrupt) Daily Worker by cutting off its Party funding. Johnny Gates saw the writing on the wall and resigned from the organization that he had served since he was 17, mournfully stating: “the Communist Party has ceased to be an effective force for democracy, peace, and socialism in the United States. The isolation and decline of the Communist Party have long been apparent… I have come to the reluctant conclusion that the Party cannot be changed from within, and that the fight to do so is hopeless.” But he affirmed that “the same ideals that attracted me to socialism still motivate me” — the problem was that he “did not believe it was possible any longer to serve those ideals within the Communist Party”. Gates distanced himself from the legions of reactionary apostates, clarifying: “I did not quit the American Communist Party in order to embrace the ideas of [US Secretary of State] John Foster Dulles or to enlist in the Cold War”. He spent the rest of his life working as a researcher for a labor union. His hope was that the youth would revitalize radical politics by creating a democratic socialist mass organization.

John Steuben was less optimistic. Steuben had spent years organizing steel workers and fighting brutal union-busters and strike-breakers; when the re-imposed Soviet puppet government in Hungary led by János Kádár threatened to execute Hungarian workers for going on strike, Steuben — who had just written a book called Strike Strategy (1950) — quit the CPUSA and begged American Communists to “repudiate everything that smacks of Stalinism and chart a course on the basis of the true interests of American workers and the American people as a whole” rather than remain “a native auxiliary of a foreign party” which had become “morally bankrupt”. His post-Party plan was to live out the rest of his life “in agony and silence”. He died of heart failure a few months later [fate is as subtle as it is fair]. Howard Fast broke with and denounced the Party around the same time as Steuben, outraging his jilted comrades by publicly urging Soviet writers to speak out against their government’s invasion of Hungary. Fast was a socialist-realist novelist who had been “the single most important literary figure in the CPUSA” and a household name in the Soviet Union, where he was considered “the representative contemporary American writer” and assigned as required reading in Soviet schools.20 Fast’s Communism earned him the adulation of the Russians but came at a price back home — American schools banned his books, universities barred him from speaking on their campuses, the federal government prevented him from leaving the country, and his refusal to “name names” for Congress earned him a three-month prison sentence. Behind the scenes, Fast’s loyalty to his fellow Jews had been causing friction between him and the Party since 1949, when he asked Alexander Fadeyev, the Chairman of the Union of Soviet Writers, about evidence he had received pointing to systematic antisemitic policies and executions in the Soviet Union. Fadeyev flatly denied that antisemitism existed in the USSR. After Fast heard that a Jewish Russian poet had been killed by the Soviet State, he confronted a Pravda correspondent, who complained: “Howard, why do you make so much of the Jews, Jews, Jews? That is all we hear from you!”21 The CPUSA privately berated him for the alleged deviations from Marxism-Leninism in his work. When Fast finally quit after the events in Hungary, it made the front page of the New York Times. The CPUSA and the CPSU joined forces in denouncing him in rabid, seething statements; as Badiou argued in his analysis of The Decision, to break away from the collective subject that gives your life value is to become worthless. Anxious to put a nail in the Party’s coffin, the FBI was hopeful that Fast would become an informant and help them turn other “wavering” Jewish members of the Party, but, to their disappointment and to his credit, he never truly “crossed over” — Fast’s whiny self-flagellation and desire for a return to mainstream respectability were accompanied by public reassurances that he still “utterly despised all that anti-Communists represented”.22 Even without the help of accelerants like double agents and COINTELPRO disruption tactics, however, the relationship between American Jews and the CPUSA/CPSU had already been damaged beyond repair. Jewish Life magazine, a publication affiliated with the Party, felt “anguished” at the thought of having “Jewish blood on their hands” because they had spent a decade ignoring or denying antisemitic State violence in the Soviet Union, and after backing the doomed Johnny Gates reform faction, they decided to leave the Communist movement, shift toward a form of socialism that was more “democratic” and “humanist” than Marxism-Leninism, and rename themselves “Jewish Currents”. Fadeyev, the Soviet intellectual who dismissed Fast’s concerns about Jews in the USSR, committed suicide after the 20th Congress in 1956. He was despondent over the “physical extermination” of “the best cadres of literature” and convinced that “the path by which” Khrushchev’s “self-confident, ignorant” bureaucrats intended to “correct the situation” would only continue to betray “the great teachings of Lenin” and “debase, persecute, and destroy” literature. At the end of his suicide note, which was addressed to the Central Committee of the CPSU, Fadeyev wrote: “My life as a writer loses all meaning, and I leave this life with great joy, seeing it as a deliverance from this foul existence, where meanness, lies, and slander rain down on me”. Left unmentioned was Fadeyev’s direct collaboration in the Stalin Administration’s destruction of the best cadres of Soviet literature.

After fighting and losing a series of agonizing power struggles, Steve Nelson gave up on his Party after 33 years of membership, but he did not fall into despair. He remained a radical activist, organizing protests against the Vietnam War and providing material support to the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. He was heartened by the rise of Eurocommunism, which he saw as the fulfillment of the “democratic Marxist” reform agenda he had been unable to implement in the CPUSA.23 The small group of reformers who remained in the Party tried to avoid despair, too, but it was not easy for them to follow Badiou’s admonition to “keep going even when you have lost the thread… when the Event itself has become obscure, when its name is lost”. After the dust had settled in 1958, the Party was left with only 3,000 people nationwide — they had lost 96% of their members in the span of a decade. Among those who remained were Al Richmond, Ben Dobbs, and Dorothy Healey, dissidents who refused to abandon their tiny, powerless, intellectually-destitute Party. That changed after the USSR’s response to the Prague Spring.

When Healey visited Prague in her capacity as a CPUSA representative, she had been “tremendously enthusiastic” about the “democratic communist” future envisioned by reformist politicians like Alexander Dubček and forward-thinking intellectuals like Radovan Richta and Eduard Goldstücker.24 Their coalition of moderate Party leaders, disgruntled technocrats, and downtrodden writers successfully seized control of the Party-State apparatus in early 1968, and they had two goals: transform the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and transform the Czechoslovakian economy.25 They were fed up with their archaic, heavy-handed Stalinist mode of governance, and they intended to replace it with a streamlined, professionalized political system that separated Party politics from State administration and safeguarded civil liberties.26 They also believed that the means and forces of production had been sufficiently developed to warrant a progression beyond the inefficient, brute-force Stalinist command economy, but “democratic communism” was not taken to mean a free association of individuals liberated from the Law of Value — class struggle was not part of their plan. The Czech intellectuals envisioned a state-of-the-art, meritocratic, consumption-driven market economy. They understood this proposed system as an advanced form of socialism rather than another form of capitalism, which, to be fair, is not much of a stretch once you have already accepted the idea of “socialist commodity production” for exchange in the international marketplace. The technocrats would allow the workers of Czechoslovakia to democratically operate their own workplaces through Workers’ Councils (unless their workplaces were unprofitable, in which case they would be shut down by the State), but they were troubled by the excessively egalitarian distribution of wages under the Stalinist status quo and believed it would be more efficient and fair to determine wage levels based on workers’ contributions to “social progress”. Their conception of political novelty was purely formal and technological.

The CPUSA leaders were very upset about the Czech Communists’ deviations from the Soviet Way; the official Party line was that Dubček was a puppet of the American and West German imperialists. The CPSU — which was now led by Leonid Brezhnev’s ultra-militaristic administration — was even more upset; the Soviet Union and its proxy states invaded Czechoslovakia to suppress the “counter-revolution”. Dubček got off light compared to his Hungarian antecedent Nagy; rather than hang him, Brezhnev and the Czech Old Guard merely removed him from his post, kicked him out of the Party, and sent him to work for the Forestry Service. Healey and fellow American Communist Party reformer Ben Dobbs were so infuriated by this interference that they triggered the nuclear option: they violated democratic centralism, publicly speaking out against the Soviet invasion to defiantly defend “the Czech Communists’ right to create their own vision of socialism”. Healey believed that the true source of Soviet opposition to the Prague Spring was the risk that the Czech attack on their rigid, stagnant bureaucratic apparatuses could inspire a similar political-modernization movement in the Soviet Union.

Maybe she was onto something — in one of the last texts Lenin ever produced, “Notes on the Question of Nationalities or ‘Autonomization’” (1922), he warned of the “nationalist-socialist” threat posed to revolutionary internationalism by the “Great-Russian chauvinist State apparatus which we took over from Tsarism and slightly anointed with Soviet oil” but could not smash “without the help of other countries and because we have been ‘busy’ most of the time with military engagements and the fight against famine”. Lenin not only defended the “autonomy” of the small socialist republics against the “tyrannical Russian bureaucrats” and “vulgar Great-Russian bullies” at the helm of the unreformed Russian administrative machinery — he also defended Georgia’s “freedom to secede from the Soviet Union” against the campaign led by Stalin, Caucasus Bureau Chairman Sergo Ordzhonikidze, and Secret Police [Cheka] Chief Felix Dzerzhinsky to turn that formal freedom into “a mere scrap of paper”. The terminally-ill Lenin begged Trotsky to “undertake the defense of the Georgian Affair,” and Trotsky did secure several policy concessions for the Georgians from the Politburo, but he was soundly defeated in his attempts to depose Ordzhonikidze and to extend an olive branch to the dissident Georgian Communists, so he abandoned his half-hearted effort to limit the ability of the Russian Party-State to infringe on the national self-determination of the Soviet Union’s constituent republics.27 Bukharin put up more of a fight than Trotsky, but he lost, too. And that was that. The machine was not interested in dismantling itself.

After Brezhnev’s soldiers invaded Prague in August of 1968, Healey’s ally Al Richmond went to Czechoslovakia on a fact-finding mission. When he returned, his praise for the Czech reformers and criticism of the Soviet Union’s military intervention was met with such vigorous and belligerent backlash from other Party members that Richmond was forced to resign from his position as the editor of the Party’s West Coast publication, People’s World. The Party brass also mobilized against Healey and removed her from her regional leadership position, but she refused to quit the organization, reasoning: “I had been in the Party too long, put too much into it, and gained too much from my association just to hand it over… I still felt, as I had since the mid-1950s, when I first went into active opposition, that the Communist Party was something greater than the sum total of its parts.”28 But “now, for the first time in my years as a Communist, I was no longer proud of being in the Party and no longer tried to recruit people for it”.

Healey wrote that she “might have drifted indefinitely had matters not been brought to a head by the Party’s reaction to Al Richmond’s autobiography, A Long View from the Left (1972),” which was an attempt to supply the “new generation of revolutionaries” with wisdom derived from Richmond’s “lifetime of revolutionary commitment”. The Party leaders were furious that Richmond aired out their dirty laundry, continued to praise the Czech reformers, and critiqued the stifling and subservient dogmatism of Official Communism, so they expelled him from the Party he had joined when he was 15. The Central Committee, which was now controlled by Gus Hall following the deaths of Bill Foster, Gene Dennis, Ben Davis, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn in the early 1960s, upped the ante: anyone who refused to condemn Richmond’s “slurs and slanders of the experience and role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union” would also be expelled.29 Healey considered waging an inner-Party reform struggle, but she expected that strategy to result in a split, and she did not want to be “a guru of a little splinter group” like Jay Lovestone. So at long last (and against the advice of other “free thinkers” in the Party like Gil Green and Rose Chernin) she gave up. When Cannon’s Trotskyists left the Party four decades earlier, around the same time a 14-year-old Dorothy Healey joined the Party, they emphasized that the central issue that led to their defection “was not simply a question of democracy” but a question of “the program of Marxism”; when Healey quit, she stated that “the primary question is the lack of Party democracy and the use of a distorted version of democratic centralism to compel approval of decisions made without prior discussion among the membership”.30 Like Fast and Gates, Healey wanted to make it clear that her “resignation from the Communist Party will not bring comfort to anti-Communists on either the right or the left. My hatred of a capitalism which degrades and debases all humans is as intense now as it was when I joined the Young Communist League in 1928. I remain a communist, as I have been all my life, albeit a communist without a Party.” She later wrote: “my loyalties are to a vision of socialism, not to a particular organization,” and she and Ben Dobbs described themselves as “lowercase-c communists”. In The German Ideology, Marx criticized Ludwig Feuerbach for thinking “it possible to change the word ‘communist,’ which, in the real world, means the follower of a definite revolutionary party, into a mere category”. Did the formerly-Communist communists make the same mistake?31 Is this a conflict between Lacan’s individualistic directive not to “give ground relative to your desire” and Badiou’s collectivistic directive not to “betray the Immortal that you are”?

The following year, Healey, Dobbs, and other defeated ex-CPUSA-reformers were talked into joining the New American Movement (NAM), a recently-formed radical group which was primarily composed of highly-educated white activists huddling together after the collapse of Students for a Democratic Society. NAM was created by famous activist Staughton Lynd, future rabbi Michael Lerner, In These Times founding editor James Weinstein, and other Sixties radicals as a non-Leninist alternative to the post-New-Left formations associated with the New Communist Movement. Healey’s Phi-Beta-Kappa son Richard got in on the ground floor and Steve Nelson’s NASA-astronomer son Robert pitched in; both bright, upwardly-mobile children of the Old Left upheld their parents’ radical commitments but entered into political organizing as anti-war student protesters rather than Young Communist League cadres. Socialist scholar Barbara Ehrenreich provided NAM with some publicity and prestige, but there were only about 300 of them in the early going. Stanley Aronowitz, one of NAM’s leaders, described the organization as a “movement of ideas”. NAM wanted to reverse the stagnation of American Marxist theory by infusing it with the lessons of Antonio Gramsci, Nicos Poulantzas, and Stuart Hall, updating it to account for the upheavals created by the social movements of the Sixties, and tying it more firmly to actual political practice. But their lack of resources, obsession with single-issue localism, and fixation on “democratic processes” at the expense of concrete results prevented their actual practice from achieving much.

As such, the fading NAM was amenable to the idea of a merger when Michael Harrington and his larger, better-funded Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC) approached them in 1979. Harrington had finally turned his back on his master Max Shachtman in the early Seventies, when the co-founder of the American Trotskyist movement chose to support Richard Nixon over George McGovern on the basis of McGovern’s opposition to continued US involvement in Vietnam.

Shachtman had been inching closer to wholehearted approval of American imperialism since the Fifties, when he first started to consider “an opening to the right,” an unreserved plunge into class-collaborationist labor unions and the social democratic currents of the Democratic Party. Back in the Thirties, the Trotskyists had felt compelled to expand their marginal base of support by joining large social-democratic and moderate-socialist organizations. Now that the CPUSA and the Trotskyist organizations had collapsed, Shachtman came to believe that the Democratic Party and the powerful unions aligned with it were the only sites where “the American working class as it really is” could be found; just as his anti-Stalinist Communists attempted to merge with the masses by entering the anti-Communist Socialist Party, his anti-Stalinist Socialists would merge with the masses by becoming de facto Democrats. Shachtman was not content to passively “meet the people where they were,” however — his initial goal was to “realign” the Democratic Party, to use it as a vessel to push the United States closer and closer to full-blown social democracy (and eventually socialism).

Unsurprisingly, the ties of influence between the Shachtmanites and the DC progressives did not flow in the direction the socialists had expected. As he came into proximity to elite labor statesmen like George Meany and Walter Reuther, Shachtman incrementally abandoned his Third Camp position and slowly crossed over into the Washington Camp. It was clear to him that the American working class had much to gain from an alliance with the imperialist ruling class, and as the Cold War heated up, he followed the reactionary union bosses as they shifted away from the left-wing of the Democratic Party toward the political faction that was most closely aligned with the American military-industrial complex. The once-precocious communist grew up. Shachtman dutifully condemned the Cuban Revolution as “Stalinist expansionism” and supported the Bay of Pigs invasion. He endorsed Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War and called for US participation to continue “indefinitely” until the Viet Cong had been “annihilated”. The Shachtmanites dropped the word “Socialist” from their name and started calling themselves “Social Democrats, USA”. Harrington led a faction of left-wing Shachtmanites in splitting off to create a new socialist organization, but the social democrats who remained had bright futures ahead of them: the national chairman of their rebranded youth wing, Joshua Muravchik, later served as a board member at Freedom House and was a strong supporter of George W. Bush; their executive director, Carl Gershman, became a Reaganite and currently serves as the president of the National Endowment for Democracy; Jeane Kirkpatrick, another prominent Shachtmanite, became Reagan’s foreign policy adviser and Ambassador to the United Nations — they even named an anti-Communist doctrine after her. Shachtman died three days before his man Nixon was re-elected in 1972. Jim Cannon, who never quit the Socialist Workers Party, died two years later. In spite of their acrimonious split and divergent paths, Shachtman always regarded Cannon as the greatest leader ever produced by American Communism.

Harrington stood by Shachtman throughout the 1960s, but his extreme position on Vietnam and his rejection of the “socialist” signifier were too much for Harrington to stomach. He wanted his DSOC to scrap Shachtman’s right-wing 1960s pivot and return to Shachtman’s moderate 1950s strategy; like the Independent Socialist League, the DSOC was designed to serve not as a mass organization in-itself but as a left-wing pressure group orbiting and influencing the Democratic Party. Harrington used his charisma and his vast theoretical and historical knowledge to persuade young student activists and radical intellectuals to settle for “the left wing of the possible” — genuine societal transformation would be on the agenda one day, far off in the distant future, but, for the time being, the Democrats and the business-unionists had a monopoly on political possibilities. Harrington justified his submissive electoralism by describing his ideology as “visionary gradualism,” and he justified his call for an endless march through the Establishment’s institutions by describing himself as a political “long distance runner”. Unlike Shachtman, Harrington never supported the war in Vietnam, but unlike Hal Draper, the famous left-Shachtmanite who broke from the rest of them by siding with the New Left activists, Harrington did not exactly oppose the American invasion. He was dismayed at the prospect of the “Stalinist” Communist Party of Vietnam seizing control of their entire country, and he denounced anti-war protesters for failing to disavow the Viet Cong. Although he supported Zionism on the basis of its status as a “national liberation movement,” he did not feel the same way about the National Liberation Front of Southern Vietnam — it did not share the State of Israel’s “democratic” values. Another factor preventing him from vocally opposing the war: his desire to avoid jeopardizing his job in the Johnson Administration or alienating his pro-war labor aristocrat allies. But when Nixon swept the Democrats out of power in 1968, Harrington was suddenly free to speak out against the war, and his opposition to Nixon’s Vietnam policies played a key role in his creation of the DSOC in 1973 together with leftist union officials and Dissent’s Irving Howe, another former Shachtman protégé.